Negligence Case Examples: Real Court Decisions That Shaped Personal Injury Law

Negligence Case Examples: Real Court Decisions That Shaped Personal Injury Law

Someone's carelessness injures you—what happens next? Real courtroom battles show exactly how negligence law works when rubber meets road. Through actual verdicts and settlements, we'll see judges weighing evidence, juries assigning blame, and attorneys fighting over compensation dollars.

What Legally Defines a Negligence Case in US Courts

Personal injury attorneys build most lawsuits on negligence foundations. But here's the thing: courts won't just nod along when you say someone acted carelessly. They demand proof of very specific legal requirements, developed over hundreds of years through common law decisions.

The Four Elements Required to Prove Negligence

Win a negligence lawsuit? You'll need all four elements proven. Fall short on just one, and your case collapses—even with devastating injuries and a clearly careless defendant.

| Element | What It Means | Evidence You Need | How Defendants Fight Back |

| Duty | Defendant had a legal responsibility to act carefully toward you | Show your relationship with defendant created this obligation—customer/business, doctor/patient, driver/other drivers | Claim they owed you nothing special; you were trespassing; state law limited their responsibility |

| Breach | Defendant failed to act as carefully as a reasonable person would | Demonstrate their actions fell short of what prudent people do in similar situations | Produce evidence showing their behavior was actually reasonable; they followed industry rules; an emergency forced quick decisions |

| Causation | Defendant's carelessness directly caused your injuries (both in fact and foreseeably) | Prove their breach directly resulted in your harm; your injuries were a foreseeable consequence | Point to something else that broke the causal chain; blame a different source for your injuries |

| Damages | You suffered real, measurable harm | Document your physical injuries, financial losses, or emotional trauma with specifics | Downplay how badly you're hurt; point to health problems you had before; question whether you needed all that treatment |

Plaintiffs carry the full burden here. Defense attorneys just need to plant reasonable doubt about one element—any single element—to sink your claim entirely. That explains why plenty of cases involving obvious carelessness never result in payment.

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

How Duty of Care Is Established in Different Scenarios

The legal duty you're owed changes dramatically based on your relationship with the defendant. Store owners owe customers extensive safety obligations but almost nothing to burglars. Physicians must provide patients with care matching their specialty's standards. Anyone behind the wheel owes everyone else on the road a responsibility to drive safely.

Back in 1928, Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Co. set boundaries still controlling duty analysis today. Railroad workers shoved a passenger carrying fireworks (hidden in newspaper wrapping) onto a moving train. The package exploded. Scales standing on the platform toppled onto Helen Palsgraf, who was waiting far away from the commotion. New York's highest court said no—the railroad owed her nothing. Her injury was too bizarre, too unforeseeable, even though employees clearly acted carelessly toward the passenger with the package.

Foreseeability still drives duty analysis in modern courts. Your broken front step? You owe a duty to the mail carrier who might trip. That same broken step injures a burglar fleeing with your TV? Probably no duty there.

The risk reasonably to be perceived defines the duty to be obeyed.

— Benjamin N. Cardozo

Landmark Medical Malpractice Negligence Cases

When doctors, nurses, or hospitals provide substandard care that harms patients, these tort liability cases require medical experts to explain what competent professionals would have done differently.

Helling v. Carey (1974) changed eye care across America overnight. Barbara Helling saw Dr. Carey repeatedly over several years, complaining about vision trouble. The doctors never tested for glaucoma—standard practice said patients under 32 didn't need screening. She finally got tested at 32. Result? Permanent, irreversible vision loss from advanced glaucoma.

Washington's Supreme Court dropped a bombshell: following what every other ophthalmologist does doesn't automatically mean you provided reasonable care. When a simple, inexpensive test could have prevented blindness, saying "that's how we've always done it" isn't good enough. Within months, the ophthalmology profession lowered recommended screening ages nationwide.

Ybarra v. Spangard (1944) solved a frustrating problem for surgical patients. Bernard Ybarra went in for an appendectomy. Standard surgery. He woke up with excruciating shoulder pain that eventually became permanent paralysis—in his shoulder, nowhere near his appendix. Because he'd been unconscious, Ybarra couldn't identify which surgical team member caused the injury.

California's Supreme Court created a crucial exception to normal proof requirements. When you're unconscious during treatment and suffer an unusual injury, and multiple medical professionals had control over your care, the burden flips. Now defendants must explain what happened. This doctrine (res ipsa loquitur—"the thing speaks for itself") prevents medical teams from hiding behind collective silence about operating room mistakes.

Canterbury v. Spence (1972) established informed consent rules now used throughout most states. Dr. Spence performed spinal surgery on Jerry Canterbury without mentioning the 1% paralysis risk. That rare complication occurred. Canterbury sued, arguing he would have declined surgery had he known. The D.C. Circuit Court created a new standard: physicians must reveal material risks that reasonable patients would consider important when deciding whether to consent. Technical competence isn't enough—doctors must communicate honestly about what could go wrong.

Premises Liability: When Property Owners Failed Their Duty of Care

Own or control property? You're legally required to keep it reasonably safe for lawful visitors. Ignore hazards or fail to warn about dangers, and you'll pay for resulting injuries.

Connecticut courts heard a case about a woman brutally attacked in a mall parking garage. The property owner had eliminated security patrols months earlier, cutting costs. Here's the kicker: multiple assaults had already occurred in that same garage. The court ruled that once property owners know criminal activity keeps happening, they must implement reasonable security measures. This accident litigation example proved premises liability reaches beyond slippery floors and broken railings into inadequate security for foreseeable crimes.

Everyone knows the slip-and-fall scenario, right? Anjou v. Boston Elevated Railway Co. (1911) clarified how these cases actually work. A banana peel on a train platform sent a passenger tumbling. The railroad's defense: "Prove exactly when someone dropped that peel and how long it sat there." Massachusetts courts rejected this impossible burden, ruling that the peel's dirty, trampled appearance created reasonable inference that it had been there long enough for employees to spot and remove during normal inspections.

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Snow and ice cases get tricky, especially up north. Most states apply "natural accumulation" rules—property owners aren't liable for injuries from naturally falling snow and ice until reasonable time passes for removal. But create a hazard through negligent snow removal (like piling snow that melts and refreezes into dangerous ice sheets), and that protection vanishes instantly.

A heartbreaking case involved a young child drowning in an apartment complex pool. The required safety fence had been removed. The gate lock was broken. Despite posted "No Lifeguard on Duty" warnings everywhere, the property owner lost big. Why? Courts recognize "attractive nuisance" doctrine—dangerous conditions that draw children who can't understand the risk require extra precautions, regardless of warning signs kids won't read or comprehend.

Motor Vehicle Accident Negligence Precedents

Traffic collisions generate more negligence lawsuits than any other category. Through decades of cases, courts have built detailed standards for driver behavior, creating negligence precedent that shapes how insurance adjusters evaluate every claim.

Hammontree v. Jenner (1971) tackled sudden medical emergencies behind the wheel. Jenner suffered an epileptic seizure while driving, causing his car to plow into Hammontree's bicycle shop. California's Supreme Court drew important distinctions: drivers with known seizure disorders who get behind the wheel anyway aren't automatically negligent, but they can face liability if they knew or should have known about the risk. The ruling separated truly sudden, unforeseeable medical events (which excuse negligence) from driving despite diagnosed medical conditions that make safe operation unlikely.

Distracted driving lawsuits evolved alongside technology. Early cellphone cases established that causing a crash while using your phone can be negligent even when phone use was perfectly legal. One New Jersey case went further: a teenager faced liability for texting her boyfriend while he drove, knowing he'd read and respond to her messages immediately. Liability expanded beyond just the driver to anyone knowingly contributing to distracted driving.

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

"Last clear chance" doctrine emerged from railroad crossing accidents but now applies to all vehicle collisions. Even when plaintiffs act negligently themselves, defendants who have the final opportunity to avoid the crash bear responsibility for failing to act. A jaywalking pedestrian might share fault, but a driver who spots the pedestrian with plenty of time to brake and chooses not to remains liable.

Drunk driving cases typically trigger punitive damages beyond simple injury compensation. Texas courts awarded $30 million in punitive damages against a drunk driver who killed four family members, despite the driver being essentially judgment-proof with no assets. These verdicts aim to deter similar conduct, even when collecting the judgment proves impossible.

Failure to maintain vehicles creates liability when mechanical problems cause collisions. A trucking company faced massive damages after brake failure caused a multi-vehicle pileup on the interstate. Maintenance logs proved the company had ignored repeated mechanic warnings about deteriorating brakes. This accident litigation example shows negligence isn't always about doing something careless—sometimes it's about failing to fix known dangers.

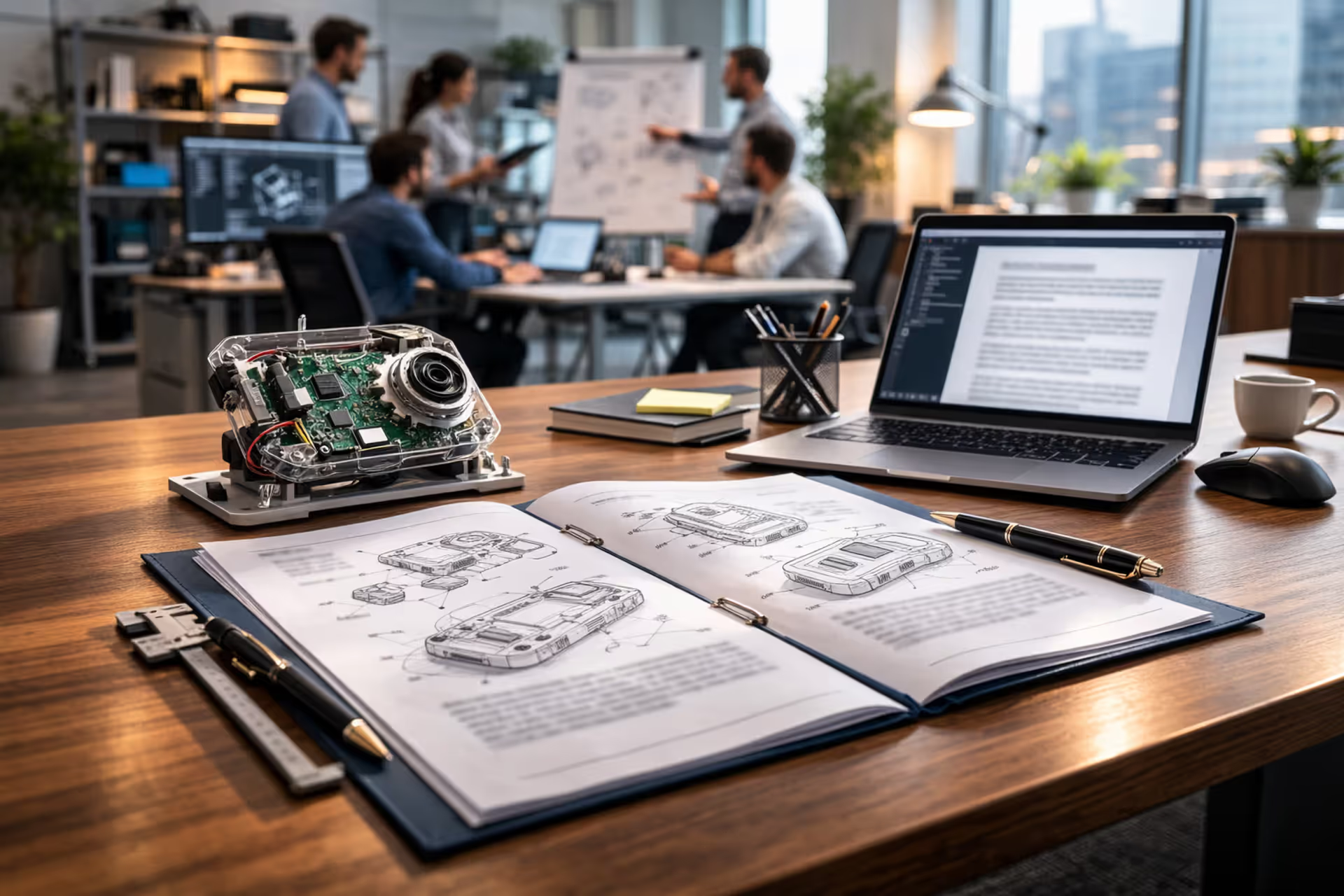

Product Liability and Manufacturer Negligence Examples

Manufacturers face three distinct obligations: design safe products, manufacture them without defects, and warn buyers about non-obvious dangers. Drop the ball on any one, and you've opened the door to tort liability.

Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Co. (1981) became the poster child for corporate indifference to human safety. Ford's Pinto had a fuel tank design that caused fires during rear-end collisions. Internal memos revealed Ford had calculated that settling burn injury claims would cost less than redesigning the tank ($11 per vehicle). When Richard Grimshaw suffered horrific burns in a Pinto fire, jurors awarded $125 million in punitive damages (judges later cut this to $3.5 million). The case cemented a crucial principle: manufacturers can't run cost-benefit analyses that trade human lives for profit margins.

When the cost of prevention is less than the cost of harm, failing to act is negligence.

— Judge Learned Hand

The Dalkon Shield disaster injured thousands of women through a defective intrauterine contraceptive device. The manufacturer had data showing serious infection risks but kept marketing the product without adequate warnings. Courts found liability for negligent failure to warn, even though each device was manufactured perfectly according to design specifications. Here's why that matters: a product can be flawlessly made yet still negligently designed or marketed.

MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. (1916) revolutionized who manufacturers owe duties to. MacPherson got injured when a defective wooden wheel on his Buick collapsed. Buick's defense: "We didn't sell the car to MacPherson—he bought it from a dealer—so we owe him nothing." New York's Court of Appeals, with Justice Cardozo writing, ruled that manufacturers owe safety duties to all foreseeable users, not just direct purchasers. This eliminated the "privity of contract" requirement that had protected manufacturers from most negligence claims for decades.

Children's products face intense scrutiny. One toy manufacturer lost despite meeting all federal safety standards and including age-appropriate warnings. A three-year-old choked on a small detachable part from his older brother's toy. Courts reason that manufacturers must anticipate foreseeable misuse, including younger siblings accessing toys marketed to older kids.

Pharmaceutical litigation requires proving the manufacturer knew or should have known about risks it concealed or downplayed. A patient with severe liver damage successfully sued after evidence showed the drug manufacturer had received hundreds of adverse event reports but delayed updating warning labels for two years. The "learned intermediary doctrine" typically requires warning prescribing physicians rather than patients directly, but manufacturers must provide complete, current information about all known risks.

How Courts Determine Damages in Negligence Cases

Prove negligence? You're halfway home. Now comes the fight over dollars and cents—establishing the full extent of harm you suffered to receive fair compensation.

Compensatory vs. Punitive Damages in Notable Cases

Compensatory damages try to make injured plaintiffs whole by covering medical bills, lost paychecks, property damage, and pain and suffering. These awards attempt restoring plaintiffs to their pre-injury condition, though obviously no amount of money truly compensates for permanent disability or death.

Economic damages like hospital bills and lost wages need documentation. Consider a construction worker paralyzed when scaffolding collapsed. He'll receive compensation for past medical expenses plus projected lifetime care costs, calculated using expert testimony about life expectancy, future medical needs, and inflation. Lost earning capacity looks beyond current salary to career advancement the injury prevented—a 30-year-old supervisor who'd likely have become a project manager sees different calculations than a 60-year-old near retirement.

Non-economic damages for pain, suffering, and lost enjoyment are inherently subjective. Juries weigh injury severity, permanence, and daily life impact. A professional violinist who loses finger dexterity suffers greater loss of life enjoyment than someone whose hobby is reading, even with medically identical hand injuries.

Punitive damages punish especially outrageous conduct and deter others from similar behavior. Courts save these for cases involving intentional wrongdoing, fraud, or reckless indifference to obvious safety risks. The Supreme Court has capped punitive damages at roughly nine times compensatory damages in most situations, finding larger ratios violate constitutional due process protections.

| Case Name | Year | Type of Negligence | Damages Awarded | Key Precedent Set |

| Liebeck v. McDonald's | 1994 | Inadequate warning about dangerously hot coffee | $640,000 final ($160,000 compensatory plus $480,000 punitive, slashed from jury's $2.9M award) | Companies must warn about non-obvious product dangers; punitive damages justified when corporations ignore hundreds of injury reports |

| Anderson v. GM | 1999 | Defective fuel tank location causing fire | $107 million ($4.2M compensatory plus $102.5M punitive, later reduced on appeal) | Manufacturers face liability when internal cost-benefit analyses prioritize profit over consumer safety; corporate knowledge documents prove crucial |

| Grimshaw v. Ford | 1981 | Pinto fuel system design defect causing fires | $3.5 million (reduced from jury's $125M punitive plus $2.5M compensatory) | Internal memos showing deliberate safety compromises justify massive punitive awards regardless of defendant's wealth |

| Owens v. Publication Int'l | 2012 | Recipe book injury from inadequate safety warnings | $2.5 million settlement | Publishers must warn about non-obvious dangers in instructional content; "everyone knows that" defense has serious limitations |

| Escola v. Coca Cola | 1944 | Defective bottle explosion injuring waitress | Modest compensatory award (exact amount unrecorded) | Justice Traynor's concurrence laid groundwork for strict liability; manufacturers liable for defective products regardless of manufacturing care |

The infamous Liebeck "hot coffee" case gets wildly misrepresented. Stella Liebeck suffered third-degree burns requiring skin grafts when McDonald's coffee spilled in her lap. She initially requested just $20,000 for medical bills. Discovery revealed McDonald's served coffee 30-40 degrees hotter than competitors, had documented over 700 previous burn complaints, yet refused lowering temperatures because hotter coffee tasted better. The jury's punitive award equaled exactly two days of McDonald's coffee sales revenue, sending a message that ignoring hundreds of serious injury reports constitutes reckless indifference to customer safety.

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

FAQ: Understanding Negligence Through Case Examples

Understanding How Real Cases Shape Your Rights

Negligence law grows and changes through actual courtroom battles addressing real situations. Each verdict adds detail to broad legal principles, showing how courts balance competing concerns and apply centuries-old concepts to modern problems like texting while driving or defective smart home devices.

Patterns emerge clearly across these examples. Property owners who ignore known hazards face liability. Manufacturers who prioritize quarterly profits over customer safety pay punitive damages. Drivers who cause collisions through distraction or intoxication bear responsibility for all resulting harm. Medical professionals must both meet specialty standards and communicate honestly about treatment risks.

The cases also reveal what doesn't work legally. Plaintiffs unable to prove all four required elements lose, period, regardless of injury severity. Following standard industry practices doesn't automatically shield defendants when safer alternatives exist and are feasible. Signing liability waivers doesn't eliminate responsibility for gross negligence or intentional misconduct.

Considering a negligence claim? Focus obsessively on documentation. Photograph accident scenes from multiple angles and document visible injuries. Seek immediate medical evaluation and follow all treatment recommendations precisely. Preserve physical evidence—damaged products, torn clothing, broken equipment. Obtain witness names and contact information before everyone leaves the scene. These steps create the evidentiary foundation successful cases absolutely require.

The precedents we've discussed here represent a tiny fraction of negligence law's complexity. Each case turned on specific facts, and seemingly minor differences can flip outcomes completely. An attorney practicing in your state can evaluate how these principles apply to your particular circumstances and identify relevant local precedents controlling your claim's value.

Negligence law serves an important social function: encouraging reasonable care by imposing financial consequences when carelessness causes harm. These real cases demonstrate that purpose working in practice, showing courts translating abstract safety duties into concrete accountability when people and companies fall short.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on skeletonkeyorganizing.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to showcase fashion trends, style ideas, and curated collections, and should not be considered professional fashion, styling, or personal consulting advice.

All information, images, and style recommendations presented on this website are for general inspiration only. Individual style preferences, body types, and fashion needs may vary, and results may differ from person to person.

Skeletonkeyorganizing.com is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for actions taken based on the information, trends, or styling suggestions presented on this website.