Environmental Law Cases That Shaped US Climate and Pollution Policy

Environmental Law Cases That Shaped US Climate and Pollution Policy

Courtrooms, not congressional chambers, have defined modern environmental protection in America. When legislators write vague statutes with phrases like "any air pollution agent," it's judges who decide whether that covers carbon dioxide. When companies discharge waste into rivers, it's prosecutors and juries who determine accountability. The EPA's power to regulate? It's expanded and shrunk based on who sits on the Supreme Court—not what the Clean Air Act originally said in 1970.

The cases below aren't academic abstractions. They've cost companies billions in penalties, forced coal plants to shut down, and given California power to set vehicle standards that automakers nationwide must follow. They answer practical questions: Can the EPA force power plants to switch from coal to renewables? Will you go to prison for falsifying discharge reports? Can teenagers sue the government over climate change?

How Supreme Court Rulings Changed EPA Authority Over Climate Regulation

The EPA's climate authority has yo-yoed for two decades. One Supreme Court decision unleashed federal climate regulation; another slammed the brakes. Both cases interpreted the same 1970 statute—proof that environmental law depends as much on judicial philosophy as statutory text.

Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) and Carbon Dioxide Regulation

In 2003, twelve states plus environmental groups petitioned the EPA to regulate CO2 from new cars. The agency said no. Its reasoning? Carbon dioxide isn't a "pollutant" under the Clean Air Act. Plus, regulating greenhouse gases would mess with presidential climate diplomacy.

Massachusetts sued. The case reached the Supreme Court in 2006.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Here's what made this case unusual: the Bush administration argued the Clean Air Act's language—"any air pollution agent"—somehow excluded the most abundant greenhouse gas. Justice Stevens wasn't buying it. In the 5-4 decision, he wrote that Congress chose expansive language precisely to give the EPA flexibility as science evolved. Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide—all fit the statutory definition.

But the Court didn't order the EPA to regulate. Instead, it required something more limited: an "endangerment finding." The agency had to examine the science and determine whether greenhouse gases threatened public health or welfare. If yes, regulation was mandatory. If no, the EPA could walk away.

In 2009, under Obama, the EPA issued its endangerment finding. Carbon dioxide and five other greenhouse gases endangered public health and welfare. That finding opened the floodgates: vehicle emission standards in 2010, power plant regulations by 2015, methane rules for oil and gas operations. All flowed from Massachusetts v. EPA.

We are not faced with choosing between economic growth and clean air.

— Richard Nixon

The case transformed climate change from a voluntary corporate responsibility issue into a legal mandate enforceable through citizen suits.

West Virginia v. EPA (2022) and the Major Questions Doctrine

Obama's Clean Power Plan went beyond traditional pollution limits. Instead of requiring scrubbers or filters at individual coal plants, it pushed states to restructure their entire electricity grids—shifting generation from coal to natural gas and renewables. The EPA called this "generation shifting."

Twenty-seven states called it regulatory overreach.

The legal fight dragged from 2015 to 2022. By the time the Supreme Court heard arguments, the Clean Power Plan had been replaced by Trump's weaker Affordable Clean Energy rule, which Biden then revoked. The Court could have dismissed the case as moot. It didn't.

Chief Justice Roberts introduced what he called the "major questions doctrine." When agencies claim power to make decisions of "vast economic and political significance," they need explicit congressional authorization. The Clean Air Act authorizes pollution controls at specific facilities. It doesn't authorize economy-wide restructuring of energy markets.

The 6-3 decision effectively killed generation shifting as a regulatory tool. The EPA can still regulate emissions from individual power plants. It can set stringent standards that make coal uneconomical. But it can't require utilities to close coal plants and build solar farms.

What's the practical impact? It's massive. Without federal mandates, climate policy has fragmented into state-level programs. California's cap-and-trade system, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the Northeast, clean energy standards in blue states—these now drive emission reductions more than EPA rules. Red states like West Virginia continue burning coal with minimal federal interference.

Landmark Pollution Lawsuits Against Corporations

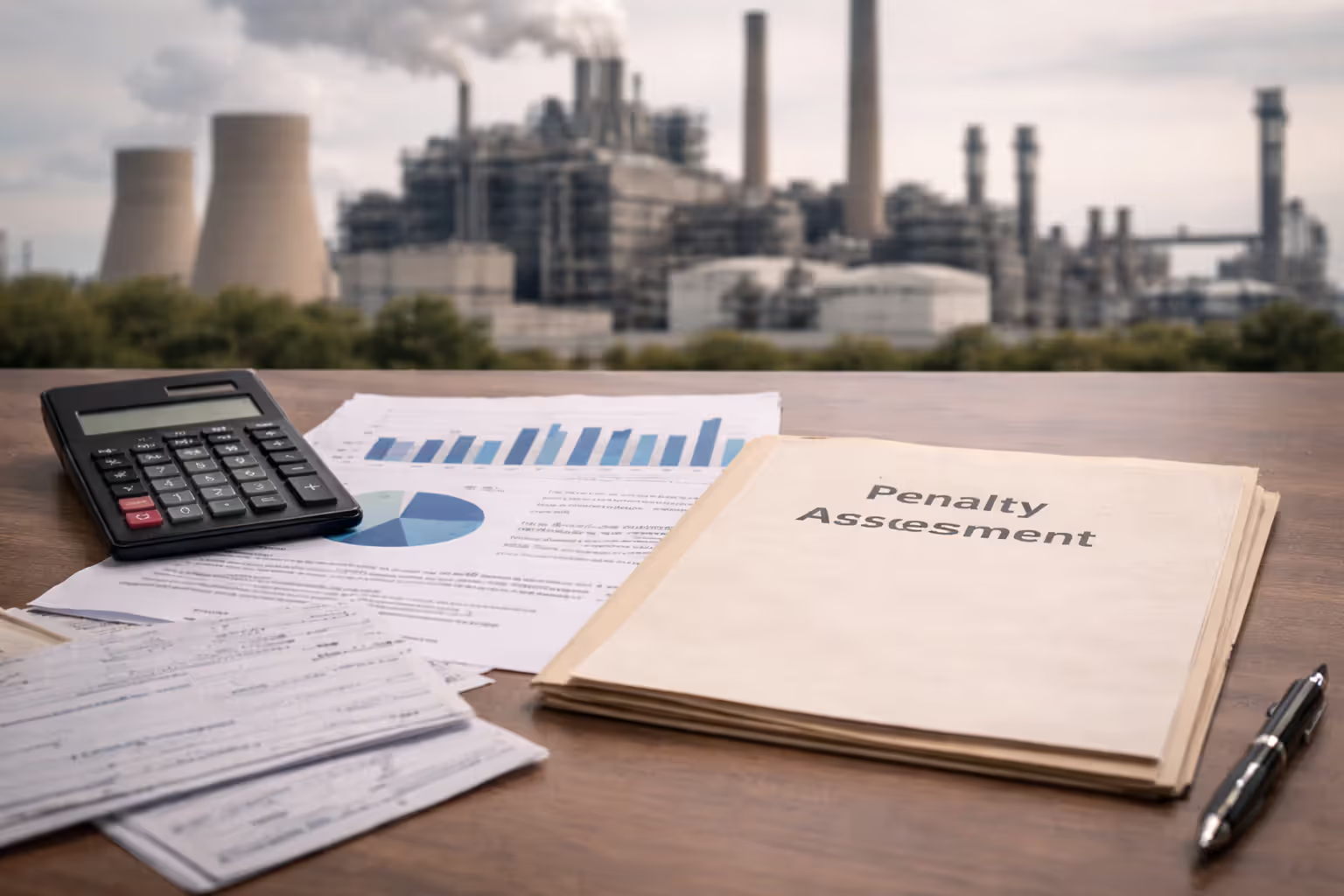

Corporate pollution cases establish what violations actually cost. Penalties vary wildly—from $50,000 slaps on the wrist to multi-billion-dollar judgments that force facility closures.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Clean Water Act Violations and Penalties

The Clean Water Act makes it illegal to discharge pollutants into US waters without a permit. Get caught, and you face penalties up to $54,833 per violation per day. Discharge something nasty for a year? That's potentially $20 million in fines.

Take Smithfield Foods in 1997. The pork producer's slaughterhouse in Virginia dumped excess phosphorus and fecal coliform bacteria into the Pagan River for years. Not massive fish kills or emergency contamination—just chronic permit violations. The Fourth Circuit upheld a $12.6 million penalty anyway. Smithfield argued these were minor technical exceedances that caused minimal harm. The court disagreed: small violations sustained over years cause cumulative damage warranting serious penalties.

Then there's Rapanos v. United States from 2006, which showed companies can sometimes win. John Rapanos filled wetlands on his property. These wetlands connected to ditches that flowed to creeks that eventually reached navigable rivers—a hydrological connection measured in miles. Did the Clean Water Act cover wetlands this far removed from major waterways?

The Supreme Court fractured into three camps, producing no majority opinion. Justice Kennedy's concurrence became the working standard: wetlands need a "significant nexus" to navigable waters to trigger federal jurisdiction. His test spawned endless litigation. Property owners argue their land doesn't significantly affect downstream waters. The EPA argues every wetland matters for flood control, water quality, and wildlife habitat. Courts decide case by case.

Air Quality Litigation Under the Clean Air Act

Air pollution cases often turn on what counts as "routine maintenance" versus "major modification." When factories upgrade equipment, they must install modern pollution controls—unless the work qualifies as routine maintenance.

Companies have exploited this loophole for decades.

Duke Energy replaced components in coal plant boilers at eight facilities in the Carolinas. The upgrades extended plant life and increased operating hours—which meant more emissions. Duke claimed this was routine maintenance. The EPA said these were major modifications requiring new pollution controls.

The case bounced through courts from 2000 to 2007. Duke initially won at the Fourth Circuit. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that any physical change increasing emissions triggers "new source review" requirements regardless of whether you call it maintenance or modification.

Duke eventually paid $60 million in penalties plus committed to $1.6 billion in pollution control upgrades. Those scrubbers and filters now remove thousands of tons of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides annually—reductions that wouldn't exist without the lawsuit.

The lesson? Creative accounting doesn't exempt you from pollution controls. Courts look at emission increases, not whether you label work as "routine."

Superfund Site Liability Cases

CERCLA—the Superfund law—imposes strict liability on anyone who contributed to hazardous waste sites. "Strict" means no intent required. "Joint and several" means the government can force one party to pay entire cleanup costs, even if dozens of companies contributed to contamination.

United States v. Monsanto Co. in 1988 showed how harsh Superfund liability can be. Monsanto operated a chemical facility that sent waste to an off-site disposal area. The disposal company had proper licenses. Monsanto followed all regulations when shipping waste. Years later, the disposal site became contaminated.

The government sued Monsanto and other chemical companies. They argued they couldn't be liable—they'd hired licensed contractors and complied with all rules. The Fourth Circuit rejected this defense. Superfund focuses on who created the hazard, not whether they acted negligently. If your waste contributed to site contamination, you're liable for cleanup costs regardless of how careful you were.

Burlington Northern's case in 2009 offered companies some relief. A railroad had leased property to an agricultural chemical distributor. Spills during loading operations contaminated soil. The government sued the railroad as a site owner and an arranger (someone who arranged for waste disposal).

The Supreme Court ruled that merely owning property where contamination occurred doesn't automatically create arranger liability. The railroad didn't arrange for disposal of waste—it leased property where a tenant conducted business. This distinction matters because it limits how broadly courts can spread Superfund liability.

Still, the railroad paid $71 million. Even a partial victory at the Supreme Court cost tens of millions in cleanup expenses.

Climate Change Litigation: State vs. Federal Disputes

America's federal system—powers divided between Washington and state capitals—creates constant environmental law tension. Industries want uniform national standards. States want authority to address local concerns. Climate change scrambles this dynamic because greenhouse gases ignore borders.

California's Battle for Stricter Emission Standards

The Clean Air Act includes a quirk: California can set vehicle emission standards stricter than federal requirements if the EPA grants a waiver. Other states can then adopt California's standards (or stick with federal rules). This exception dates to 1967, acknowledging California's smog crisis and early pollution controls.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

In 2005, California moved to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from cars and trucks. The state's standards would have required roughly 30% emission reductions by 2016—much stricter than federal rules. The Bush EPA denied California's waiver request in 2008, calling greenhouse gases different from traditional air pollutants.

California sued. So did sixteen other states, plus environmental groups and three cities.

Before courts resolved the dispute, Obama took office. His EPA reversed course and granted the waiver in 2009. Automakers grudgingly accepted the standards because California represented a massive market they couldn't ignore.

Fast-forward to 2019. The Trump EPA revoked California's waiver, arguing the state couldn't regulate greenhouse gases because they cause global rather than local harm. California sued again, this time joined by twenty-two states.

Biden restored the waiver in 2022. Which means California has now had its authority granted, revoked, and restored based entirely on which party controls the White House.

Automakers got whiplash. Several companies—Ford, Honda, Volkswagen, BMW—sided with California during the Trump years, preferring regulatory certainty even if standards were stricter. They signed voluntary agreements to meet California's rules regardless of federal policy. Other manufacturers supported Trump's revocation, hoping for weaker standards.

The fundamental legal question remains unresolved: does California's special authority extend to pollutants with planetary effects? No court has definitively answered because settlements and policy reversals keep intervening.

Multi-State Coalitions Challenging Federal Rollbacks

State attorneys general have become environmental law's most aggressive litigants. Democratic AGs sue to block rollbacks. Republican AGs challenge new regulations. These coalitions reshape policy as much as EPA rulemaking does.

When Trump repealed the Clean Power Plan and replaced it with the Affordable Clean Energy rule in 2019, twenty-two states immediately sued. Their argument? The replacement rule was so weak it violated the Clean Air Act's requirement that EPA set emission standards reflecting the "best system of emission reduction."

The D.C. Circuit agreed in 2021. The court vacated the ACE rule, finding its limited scope—only on-site efficiency improvements—ignored more effective reduction strategies. The decision came just as Biden took office, so the administration didn't appeal.

Republican-led states have pushed back equally hard against Biden regulations. Twenty-seven states sued to block EPA's 2023 vehicle emission standards, claiming they effectively mandate electric vehicle adoption beyond the agency's statutory authority. Texas, Ohio, and other states argue the EPA can regulate emissions but can't force a technology shift to EVs.

These cases won't resolve quickly. Expect 3-5 years of litigation determining which standards actually apply. Meanwhile, automakers must plan production without knowing whether they'll need to meet California's strict requirements or something more lenient.

Environmental Compliance Failures: Costly Case Examples

Penalties vary based on harm severity, violation duration, and whether companies cooperated with investigations. The comparison below shows how different violation types generate different consequences:

| Case Name | Defendant | Violation Type | Penalty/Settlement | Year | Key Outcome |

| Deepwater Horizon | BP | Oil spill, gross negligence under Clean Water Act | $20.8 billion total damages | 2015 | Largest environmental penalty in history; BP paid $4.5 billion in criminal fines plus state and federal claims; established that gross negligence multiplies penalties |

| Volkswagen Dieselgate | Volkswagen AG | Installing defeat devices to cheat emissions testing | $14.7 billion in settlements and buybacks | 2016 | Two executives imprisoned; VW admitted criminal conspiracy; required to invest $2 billion in EV infrastructure; proved software cheating triggers criminal liability |

| Duke Energy Coal Ash | Duke Energy | Illegal discharge of coal ash into rivers; Clean Water Act violations | $102 million total | 2015 | First criminal conviction for coal ash contamination; Duke admitted nine violations; required closure of ash ponds at 14 facilities across North Carolina |

| Anadarko Petroleum | Anadarko (for Kerr-McGee legacy sites) | Superfund liability for contaminated sites; corporate restructuring to avoid cleanup | $5.15 billion | 2014 | Proved companies can't spin off liabilities through corporate restructuring; held Anadarko liable for predecessor's contamination at 2,772 sites |

| Pacific Gas & Electric | PG&E | Criminal negligence causing wildfires; pipeline safety violations | $1.6 billion in fire victim compensation | 2020 | PG&E convicted of 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter; placed under five-year federal probation; established utility liability when equipment failures cause disasters |

| Renco/Doe Run Lead Smelter | Doe Run Resources Corp. | Clean Air Act violations; lead contamination | $65 million plus permanent closure | 2010 | Largest penalty for lead smelter violations; required facility shutdown; company paid cleanup costs for soil contamination affecting thousands of Missouri properties |

Notice the pattern: violations continued for years before enforcement action. Companies initially fought charges, then settled for amounts below maximum statutory penalties. And in almost every case, required remediation and upgrades cost far more than monetary fines.

Volkswagen stands out because executives went to prison. Environmental prosecutions rarely result in incarceration—most settle as civil matters. VW's case involved deliberate fraud (installing defeat device software), conspiracy (multiple executives participated), and lying to regulators (submitting false test results). That combination triggered criminal charges.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Emerging Trends in Environmental Regulation Disputes

New pollutants and problems generate new lawsuits. Courts must stretch statutes written in 1970 to address forever chemicals, teenage climate activists, and pipeline fights involving tribal sovereignty.

PFAS "Forever Chemicals" Litigation

PFAS compounds don't break down naturally. They accumulate in human bodies, contaminate drinking water, and persist for generations. Manufacturers have known about PFAS health risks since at least the 1970s. They kept manufacturing anyway.

Now thousands of lawsuits target PFAS producers and heavy users (the military, airports using firefighting foam, manufacturers of non-stick cookware). Water utilities sued to recover treatment costs. Individuals sued for health damages. States sued for natural resource damages.

The legal problem? PFAS weren't specifically regulated when most contamination occurred. Companies argue they can't be liable for substances legal to manufacture and use. Plaintiffs argue companies knew PFAS persisted in the environment and concealed health studies showing harm.

3M settled with water utilities nationwide for $10.3 billion in 2023. DuPont and spinoff companies settled for $1.18 billion. These settlements only cover public water systems—not personal injury claims from individuals with cancer, thyroid disease, or other PFAS-linked conditions. Those cases are still multiplying.

In 2024, EPA designated PFOA and PFOS—two PFAS compounds—as CERCLA hazardous substances. This designation enables Superfund cleanup authority but creates massive liability questions. Companies that legally used PFAS decades ago now face retroactive cleanup liability for contamination they couldn't have known violated any law.

Expect ten years of litigation determining who pays for PFAS remediation at thousands of sites: manufacturers, users, or both?

Youth-Led Climate Lawsuits

Teenagers suing the government over climate change face enormous procedural obstacles. Courts traditionally avoid policy questions, preferring to let elected branches make those decisions. Plus, plaintiffs must show concrete, particularized injuries—not generalized grievances shared by everyone.

Juliana v. United States epitomized these challenges. Twenty-one young plaintiffs sued the federal government in 2015, claiming fossil fuel policies violated their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property. They presented compelling evidence: rising seas threatening homes, worsening wildfires, increasing asthma from air pollution.

The district court allowed the case to proceed. The Ninth Circuit reversed in 2020, ruling that climate injuries, while real, couldn't be remedied by courts. Fixing climate change requires policy choices—shifting energy systems, regulating industries, funding infrastructure. Those decisions belong to Congress and the President, not judges.

The court's message? Your evidence is convincing, but you're suing the wrong branch of government.

State courts offer better prospects. Montana's constitution guarantees citizens' right to "a clean and healthful environment." In Held v. Montana (2023), sixteen young plaintiffs challenged a state law prohibiting agencies from considering climate impacts when permitting fossil fuel projects.

The state trial court ruled for the plaintiffs. Montana's law violated its own constitution by ignoring climate harm. The state appealed, but the trial court decision stands for now. Other states with similar constitutional provisions—Pennsylvania, Hawaii, Illinois—may see copycat lawsuits.

Indigenous Rights and Pipeline Challenges

Pipeline disputes increasingly pit tribal sovereignty against energy infrastructure. The legal framework is complicated: agencies must consult with tribes when projects affect tribal interests, but consultation doesn't equal veto power.

The Dakota Access Pipeline fight brought this tension into national spotlight. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe opposed a pipeline crossing beneath Lake Oahe, claiming it threatened the tribe's water supply and violated sacred sites. The Army Corps of Engineers approved the project anyway, completing what the tribe considered cursory consultation.

Standing Rock sued. A federal district judge found the Corps' environmental review inadequate and ordered the pipeline shut down in 2020. The D.C. Circuit reversed in 2021, allowing continued operation while the Corps completed additional review. The pipeline still operates, carrying 570,000 barrels daily.

The case established precedent: inadequate tribal consultation violates federal law, but doesn't necessarily stop projects. Courts can order additional review without shutting down operating infrastructure. This gives tribes leverage to force better consultation but rarely stops projects permanently.

Line 3 in Minnesota followed similar patterns. Tribes sued, courts required additional review, the pipeline was eventually completed despite ongoing opposition. Keystone XL represented the rare exception—Biden canceled it before construction finished, though that was political rather than judicial.

What Businesses Need to Know About Environmental Law Enforcement

Companies face three distinct liability sources: government enforcement, citizen lawsuits, and toxic tort claims. Each operates under different rules.

Government enforcement typically starts with inspections or self-reported violations (many permits require companies to report their own exceedances). Agencies can issue administrative penalties up to $25,000 per violation per day or refer cases to Department of Justice for civil or criminal prosecution. Criminal charges require knowledge—prosecutors must prove defendants knew they were violating laws or creating environmental risks.

Here's something companies often miss: the EPA's audit policy reduces penalties by up to 75% for voluntary disclosure. If you discover violations through internal audits, disclose them promptly, cooperate with investigations, and implement corrective measures, penalties drop dramatically. Companies that wait for inspectors to find problems pay full freight.

Citizen suit provisions in major environmental statutes let anyone sue violators when government doesn't act. Plaintiffs must provide 60 days' notice before filing, giving you time to fix problems. If violations continue, environmental groups can sue for injunctive relief and civil penalties. Successful plaintiffs recover attorneys' fees, making these economically viable. Unlike government enforcement, citizen suits can't seek criminal penalties—only injunctions and civil fines.

Toxic tort claims seek compensation for health injuries or property damage from pollution. These cases require proof of causation—that your specific facility caused the plaintiff's specific harm. This burden makes toxic torts harder to win than regulatory cases, but successful claims generate massive damages. The Woburn, Massachusetts case (chronicled in "A Civil Action") showed how expensive these can become even when causation evidence is circumstantial.

Smart compliance programs include: regular self-audits to catch violations early, documented training programs for employees handling waste or operating pollution controls, environmental management systems preventing violations before they occur, and immediate disclosure protocols when problems arise. The savings from audit policy penalty reductions often exceed compliance program costs within a few years.

Frequently Asked Questions About Environmental Law Cases

Environmental law evolves through litigation, not just legislation. The cases above demonstrate that environmental protection requires persistent lawsuits, substantial financial penalties, and judicial interpretations translating broad statutory language into specific requirements. Businesses in regulated industries can't ignore these precedents—they define compliance obligations and potential liabilities worth millions or billions. As PFAS contamination, climate impacts, and other environmental threats emerge, courts will continue adapting decades-old statutes to modern problems, creating precedents shaping policy for years ahead. Understanding this case law means understanding how environmental regulation actually works in practice, not just theory.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on skeletonkeyorganizing.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to showcase fashion trends, style ideas, and curated collections, and should not be considered professional fashion, styling, or personal consulting advice.

All information, images, and style recommendations presented on this website are for general inspiration only. Individual style preferences, body types, and fashion needs may vary, and results may differ from person to person.

Skeletonkeyorganizing.com is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for actions taken based on the information, trends, or styling suggestions presented on this website.