Desk with a generic service agreement, pen, and a phone showing an “I agree” email reply

Contract Law: The Core Elements, Formation Rules, and Enforceability Standards Every Party Should Know

A graphic artist finishes a brand identity package. The client withholds payment, arguing that they only "explored pricing" and never committed to the final figure. Meanwhile, a property owner claims a tenant accepted a lease extension she never put her name to — simply because she stayed in the apartment past the original term. Across town, two entrepreneurs seal a business arrangement with a firm handshake at an industry mixer, and one later realizes that casual verbal pledge might hold up in court.

These situations all hinge on identical legal doctrine. Contract law determines the point at which a promise becomes an obligation, defines what the involved parties owe one another, and establishes consequences when someone doesn't deliver. Grasping the principles of contract law — even at a surface level — heads off conflicts that inevitably cost more to litigate than they would have cost to prevent.

Note: The following content is general legal information intended for educational use. None of it constitutes legal advice. Speak with a qualified attorney about any specific contractual matter in your state.

What Contract Law Governs (and Where Most Misunderstandings Start)

At its foundation, contract law oversees voluntary exchanges between parties that produce legally recognized duties. It belongs to the civil law sphere — separate from criminal statutes (which prosecute offenses against society) and tort doctrine (which addresses non-contractual harms like negligence or defamation). When someone breaches a contractual duty, the remedy is a civil lawsuit. When someone rear-ends your vehicle, that falls under tort. The lines blur occasionally, but the categorical separation is fundamental.

Here is the biggest misconception surrounding contract law basics: most people assume that only a typed, signed, and notarized document qualifies. That assumption is wrong. A spoken arrangement to repaint a garage for $3,000 constitutes a binding deal. Two people agreeing over the phone to buy and sell a used motorcycle can produce a legitimate obligation. The real question is never whether the deal looks official — it's whether the required legal components are present.

The Statute of Frauds (addressed further below) does impose a written-form requirement on specific categories. Outside those categories, though, the default position is the reverse of popular belief: spoken promises bind unless a particular statute says otherwise.

The law of contracts represents the triumph of private ordering — the idea that individuals, not the state, are best positioned to determine the terms of their own obligations.

— Arthur Corbin, Corbin on Contracts

The Six Elements That Make a Contract Legally Binding

The elements of a contract represent the baseline criteria any deal must satisfy before courts will uphold it. Six distinct components are required. If even one is absent, the entire arrangement may collapse — or may have never existed as a legal matter.

Offer — What Qualifies and What Doesn't

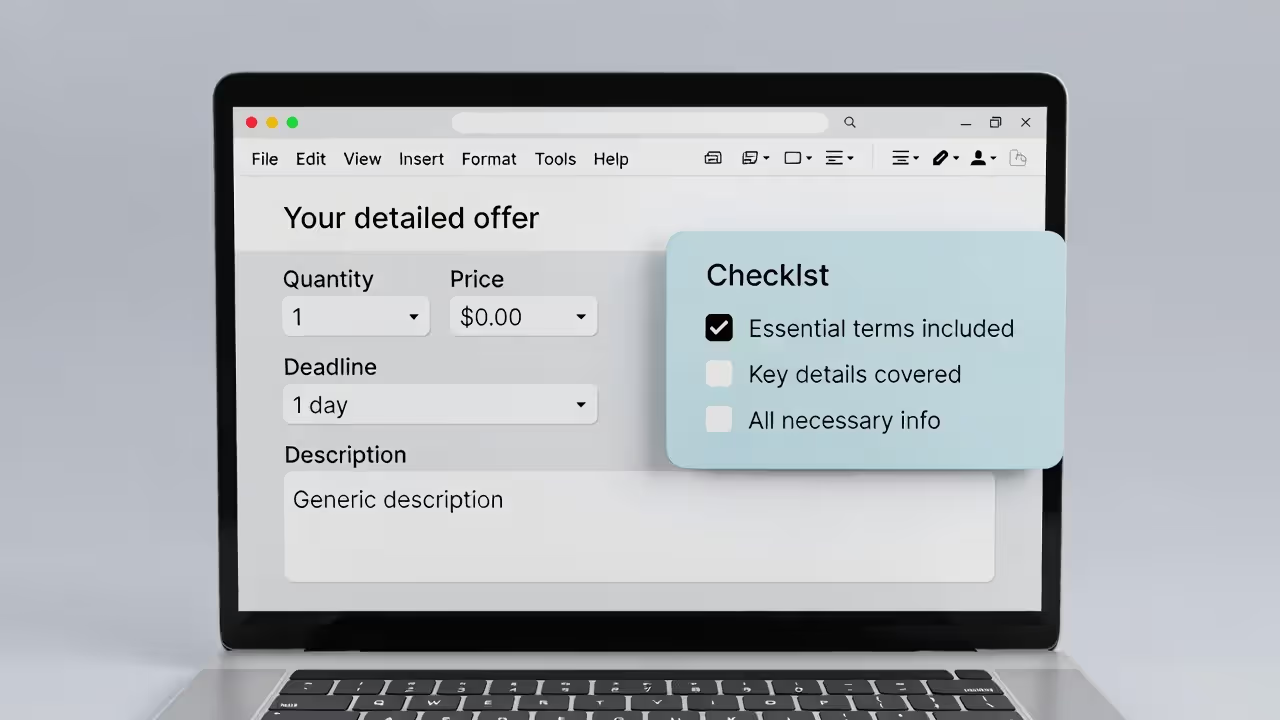

An offer amounts to a specific, unambiguous proposal communicated with the intent to create a binding duty once the other side says yes. The proposal needs sufficient detail — who the parties are, what's being exchanged, the price or pricing method, and relevant timing — so that a court could realistically enforce the terms.

What falls short: ads are typically treated as invitations to negotiate, not binding proposals — a retailer pricing a coat at $99 in its window hasn't promised to sell one to everyone who enters. Preliminary discussions ("I might be open to selling in the $50,000 range") are too indefinite. Expressions of future plans ("I'm thinking about bringing on a subcontractor next quarter") generate zero legal duties.

A useful litmus test: if a reasonable person hearing the statement would believe that responding "I agree" would finalize a transaction, the statement likely qualifies as an offer.

Acceptance — The Mirror Image Rule and Its Exceptions

Author: Andrew Whitaker;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Common law demands that acceptance correspond to the offer in every particular — known as the mirror image rule. Altering any detail transforms the response into a counteroffer, which simultaneously destroys the original proposal and substitutes a fresh one. A builder proposes a bathroom remodel at $25,000; the homeowner responds with "Yes, but at $22,000." The initial proposal no longer exists.

The Uniform Commercial Code takes a more flexible stance for goods transactions. Section 2-207 allows an acceptance containing new or different provisions to remain effective — those extra provisions function as suggested additions rather than deal-breakers, unless they fundamentally reshape the arrangement.

Some positive action is normally required to accept: verbal confirmation, executing a document, starting work, or shipping merchandise. Remaining silent almost never counts as agreement, except in narrow situations like an established pattern of prior dealings or a solicitation where both sides predetermined that no response means yes.

Consideration — Why "Something of Value" Is Non-Negotiable

Consideration refers to the reciprocal exchange at the heart of every deal — both sides must contribute something the law recognizes as valuable. Cash for labor. Products for products. A commitment to perform in return for a commitment to compensate. Even refraining from exercising a legal right (forbearance) satisfies the standard.

What doesn't hold up: actions completed before the promise was made ("You fixed my fence last spring, so here's $500 as thanks") fail because the benefit wasn't part of a current bargain. The pre-existing duty doctrine bars demands for additional compensation in exchange for performing work already owed — a plumber can't insist on a $5,000 bonus halfway through a project without offering something new in return.

A legally binding agreement explained at its most basic: both sides pledge something the other values, and that reciprocal pledge is the consideration.

Capacity, Legality, and Mutual Assent

Capacity means each participant must possess the legal standing to enter a binding arrangement. In most states, individuals under 18 retain the right to walk away from their commitments. People suffering from significant cognitive impairment or extreme intoxication may similarly lack the requisite standing. When a corporation is involved, only properly authorized representatives can commit the entity.

Legality requires a lawful objective. Any pact designed to facilitate criminal activity is automatically void. Provisions that offend public policy — excessively restrictive non-compete terms, as one example — risk being invalidated or rewritten by a judge.

Mutual assent — often described as a "meeting of the minds" — means both participants must share a common understanding of the core terms. When one side believes they're renting machinery while the other believes they're purchasing it, mutual assent never occurred. Without it, no enforceable obligation exists, regardless of how polished the paperwork looks.

Author: Andrew Whitaker;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

How a Contract Forms: The Sequence From Negotiation to Binding Agreement

The contract formation rules proceed in a recognizable order, though the specifics shift depending on whether common law or the UCC applies.

| Formation Element | Common Law (Services, Real Estate) | UCC Article 2 (Sale of Goods) |

| Offer specificity | Every material term must be defined | Open terms (price, delivery) are acceptable if intent to transact is clear |

| How acceptance works | Response must replicate the offer precisely | Response with added provisions can still qualify (§ 2-207) |

| Mirror image doctrine | Enforced strictly — any variation equals a counteroffer | Applied loosely — new terms treated as suggested additions |

| Role of consideration | Mandatory for every modification | Good-faith modifications hold without fresh consideration |

| Statute of Frauds trigger | Obligations extending beyond one year; real property transfers | Goods valued at $500 or above |

| Changing existing terms | Additional consideration needed | Sufficient if done in good faith, no new consideration necessary |

The typical progression looks like this: parties negotiate → one side extends an offer → the other may counter (eliminating the first proposal) → acceptance follows → value is exchanged → the obligation solidifies.

Under common law, the mailbox rule dictates when acceptance takes effect: the moment it's sent (dropped in the mail, transmitted electronically), not when it arrives. Post a letter of acceptance on a Monday and the deal crystallizes that day — regardless of whether the offeror opens the envelope until Thursday. Several jurisdictions have adjusted this doctrine, and it doesn't govern option contracts or scenarios where the offer stipulates a different mechanism.

Withdrawal works differently. The person who made the offer retains the right to pull it back at any point prior to acceptance — unless they received something of value to keep it open (option contract) or the other side already began performing under a unilateral arrangement. After acceptance, withdrawal is no longer available.

When a Contract Is Not Enforceable (Defenses and Voidability)

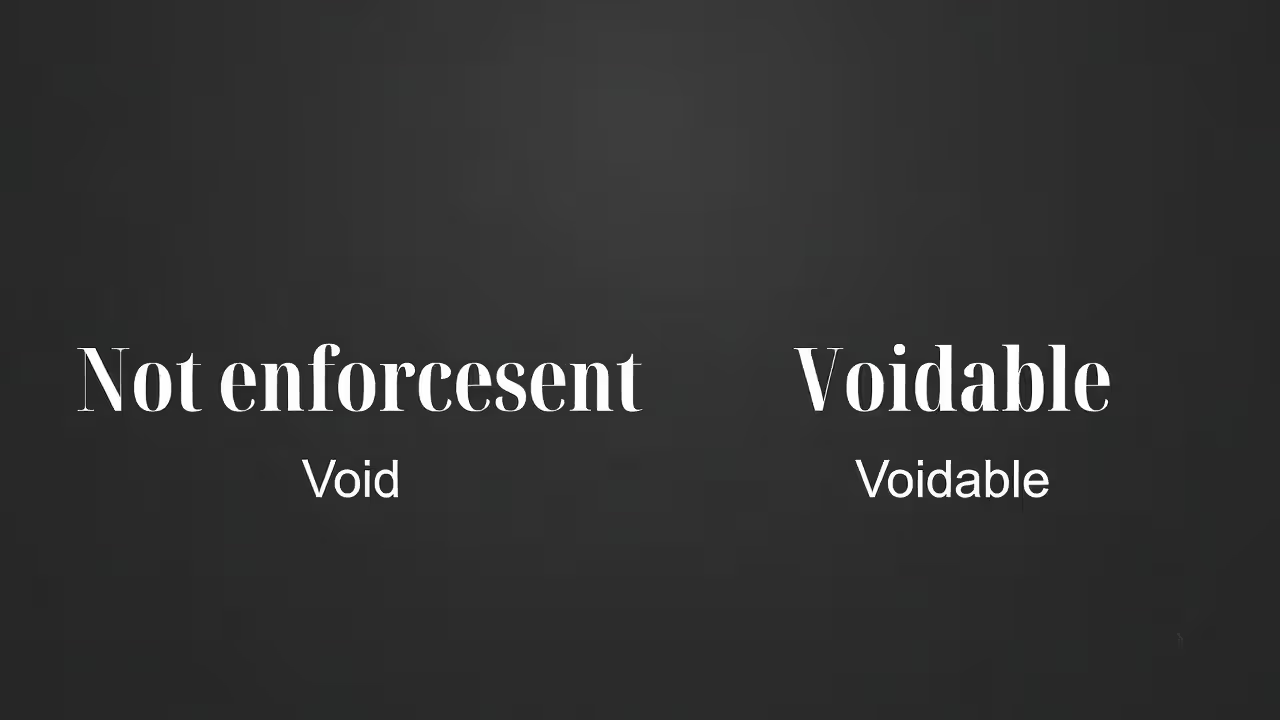

Void vs Voidable — The Distinction That Changes Everything

Author: Andrew Whitaker;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

A void contract produces no legal consequences whatsoever — the law treats it as though the deal was never struck. Arrangements with an illegal purpose and agreements involving someone with a complete absence of capacity belong in this category. No party can enforce a void obligation, and nobody needs to take formal steps to undo it.

A voidable contract, by contrast, functions normally and remains binding unless the harmed participant elects to cancel. A teenager who signs a wireless service agreement has the right to set it aside — the carrier does not. Only the shielded participant holds the cancellation power.

This contract enforceability guide distinction carries real-world weight: a fully executed document that appears rock-solid on its face can still be set aside if the conditions surrounding its execution were flawed.

Common Defenses: Duress, Undue Influence, Misrepresentation, Unconscionability

Duress arises when one side was compelled to agree through intimidation — whether physical, financial, or legal. Economic duress — "Accept these revised terms or we'll walk away and bankrupt your operation" — is gaining broader judicial recognition.

Undue influence occurs when someone leveraging a position of trust or authority pressures the other into compliance. It surfaces frequently in disputes involving elderly individuals and fiduciary relationships.

Misrepresentation involves a false assertion about a material fact that induced the other side to agree. When the falsehood was deliberate (fraud), the victim can both rescind and pursue damages. When the falsehood was unintentional (innocent misrepresentation), rescission alone is the typical remedy.

Unconscionability applies when the terms are so dramatically lopsided that enforcement would shock the conscience. Courts assess two dimensions: procedural unconscionability (did the weaker party genuinely have alternatives?) and substantive unconscionability (do the provisions overwhelmingly favor one side?). Ordinarily both must be present, although extreme substantive imbalance occasionally suffices on its own.

Mistake: when both sides share an incorrect belief about a key fact (each assumed a sculpture was a replica when it was authentic), the arrangement can be undone. A one-sided error typically provides no defense — unless the other participant was aware of, or should have recognized, the misunderstanding.

Written vs Oral Contracts: What the Statute of Frauds Actually Requires

Author: Andrew Whitaker;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

The Statute of Frauds mandates written documentation for six traditional categories (state-by-state variations exist):

Sales or transfers of real estate. Obligations impossible to complete within twelve months from the formation date. Goods transactions valued at $500 or above (UCC § 2-201). Guarantees to cover someone else's debt (suretyship). Agreements supported by consideration of marriage. An executor's personal promise to satisfy estate liabilities.

What counts as "writing" in 2026: the federal E-SIGN Act alongside the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA, enacted in 49 states) confirms that email correspondence, SMS exchanges, and digital signatures meet the statutory standard. A text conversation — "Selling my truck for $8,000, interested?" / "Done, I'll grab it this weekend" — could establish a Statute-of-Frauds-compliant sale of goods.

A frequent error: believing that every transaction demands paperwork. A verbal commitment to handle $200 worth of freelance copyediting is fully binding without any written record. The writing mandate covers only the listed categories — although documenting any meaningful deal is prudent because establishing the specifics of an oral commitment in court is substantially more difficult.

Five Common Contract Mistakes That Lead to Disputes or Unenforceability

Author: Andrew Whitaker;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Imprecise or unclear language. "Compensation due at project end" — whose definition of completion, measured how, and payable within what window? Vagueness breeds conflict. Pin down deliverables, due dates, exact dollar figures, and quality benchmarks using concrete, measurable criteria.

Omitting jurisdiction and dispute-resolution provisions. An engagement between a firm based in Texas and an independent contractor in California — whose state law controls? Absent a governing-law clause and a designated resolution process (arbitration, mediation, or a named court), both sides inherit costly ambiguity the moment a disagreement surfaces.

Ignoring conditions precedent. A home purchase hinging on mortgage approval. A consulting engagement that kicks in only after a regulatory green light. When the triggering condition isn't spelled out, one participant may treat the obligation as live while the other views it as pending.

Depending on verbal changes despite a written-modifications-only clause. Numerous formal documents contain a provision mandating that amendments be documented in writing. A casual spoken understanding to push a deadline or adjust pricing may carry no weight if such a clause is present — even when both sides acted on the spoken revision. Review the amendment provision before trusting that a handshake alteration sticks.

Believing that a signature makes a document bulletproof. Putting your name on a page does not shield the arrangement from legal challenges. Coercion, dishonesty, unconscionable provisions, absent capacity, and unlawful subject matter can all strip away enforceability. A signature serves as proof of assent — never as an iron-clad guarantee that the terms will stand.

FAQ

The doctrine governing contracts rests on foundations laid centuries ago: voluntary commitment, reciprocal exchange, and enforceable duty. The particular mechanics — offer and acceptance law, the consideration requirement, capacity constraints, Statute of Frauds classifications — compose the architecture within which every commercial transaction, employment relationship, and service engagement either survives or falls apart. Mastering the six mandatory components, recognizing when written documentation is required versus merely wise, and sidestepping the five recurring pitfalls outlined above won't eliminate the need for legal counsel on complex deals — but it positions you to identify when a binding commitment exists, when it doesn't, and when professional advice is warranted before you put pen to paper.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on skeletonkeyorganizing.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to showcase fashion trends, style ideas, and curated collections, and should not be considered professional fashion, styling, or personal consulting advice.

All information, images, and style recommendations presented on this website are for general inspiration only. Individual style preferences, body types, and fashion needs may vary, and results may differ from person to person.

Skeletonkeyorganizing.com is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for actions taken based on the information, trends, or styling suggestions presented on this website.