Co-founders signing a shareholder agreement next to an ownership percentage sheet

Shareholder Agreement Template: Essential Clauses for US Businesses

Most business partnerships start with handshakes and optimism. Then money gets tight, someone wants out, or a new opportunity divides the room. Suddenly, you're wishing you'd documented who decides what—and how.

That's where shareholder agreements come in. They're not exciting. Nobody brags about theirs at networking events. But they're the difference between a clean resolution and a legal nightmare that drains your bank account and sanity.

Here's the thing: downloading a template is easy. Using it correctly? That requires understanding what you're actually signing.

What Makes a Shareholder Agreement Legally Binding in the US

For courts to enforce your shareholder agreement, you need the basics of any contract: everyone agrees, something of value gets exchanged, nobody's breaking laws, and all signers have legal authority. Pretty straightforward—except when it's not.

The signatures matter more than you'd think. Each person signing must actually own shares in the corporation. Sounds obvious, but I've seen entrepreneurs draft agreements during late-night planning sessions, then forget to re-execute them once they officially incorporate. That creates a contract between people about shares they don't yet own. Courts won't touch it.

Here's where things get interesting. Articles of incorporation and bylaws? Public record. Anyone can look them up. Shareholder agreements stay private between owners. This lets you negotiate arrangements you'd never want competitors or customers seeing—like founder buyout terms or anti-dilution protections.

State borders matter more than most founders realize. Delaware gives corporations enormous flexibility to customize ownership rules. California? Much stricter about protecting minority shareholders from majority overreach. File your corporation in Massachusetts, and judges might view transfer restrictions differently than if you'd incorporated in Texas.

Timing trips people up constantly. Sign before incorporating, and you've got worthless paper. The proper sequence: file your articles, issue stock certificates, then execute the shareholder agreement. Some founders handle all three the same day to avoid gaps.

One crucial distinction: if you formed an LLC, you need an operating agreement, not a shareholder agreement. Corporations have shareholders. LLCs have members. The documents serve similar purposes but use different legal frameworks.

Bylaws set internal procedures—meeting schedules, officer titles, that kind of thing. But they can't create binding obligations between shareholders or override state corporate statutes. Your shareholder agreement fills that gap. It's a private contract that binds the owners personally, not just the corporate entity.

When shareholder agreements conflict with bylaws, judges typically enforce the agreement. It's more specific, negotiated directly between parties, and represents their actual intentions. Bylaws are almost boilerplate. Shareholder agreements reflect what people truly negotiated.

Core Components Every Shareholder Agreement Template Must Include

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

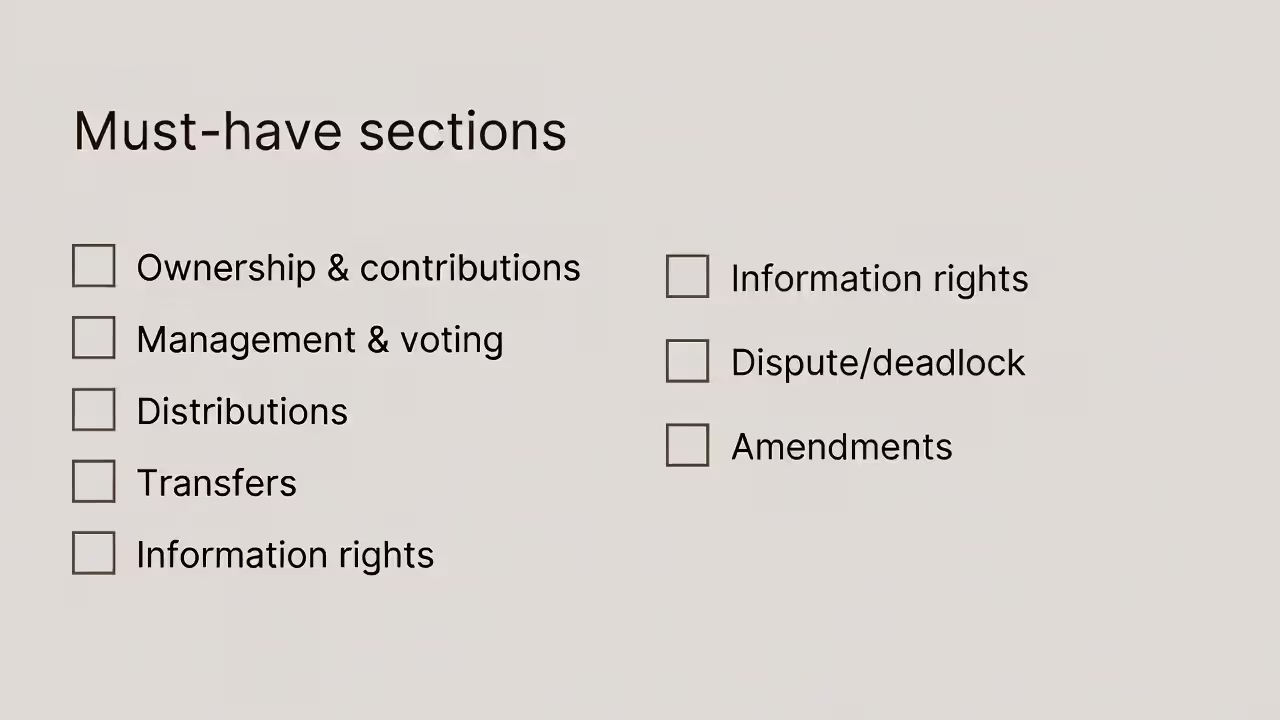

Some sections are optional. Others? Leave them out and you're asking for trouble. Three elements belong in every agreement, no exceptions.

Ownership Percentages and Capital Contributions

Vague ownership records destroy companies. Document exactly how many shares each person holds, what class of stock they own, and their percentage of total outstanding shares. Use specific numbers, not approximations.

Capital contributions get messy fast. Let's say Maria invests $75,000 upfront while Jamal contributes $15,000 but promises more later. Six months pass. Jamal hasn't ponied up. Does he lose shares? Dilute down? Get kicked out? Your agreement needs explicit answers.

Vesting schedules prevent the classic startup disaster: co-founders split equity 50-50, one person quits three months later but keeps half the company. Standard vesting runs four years with a one-year cliff. Translation: earn 25% after year one, then monthly thereafter. Leave early, forfeit unvested shares.

Document these mechanics precisely. "Shares vest over time" won't cut it. Specify the start date, cliff period, vesting schedule, what happens if employment terminates, and whether vesting accelerates in acquisition scenarios.

Management Authority and Decision-Making Powers

Who runs daily operations? Who approves major decisions? Blur these lines and you'll waste hours arguing about whether hiring a new salesperson requires a shareholder vote.

Most agreements reserve day-to-day management for officers and directors. Strategic decisions—selling the company, taking on debt, issuing new shares—require shareholder approval. Define that boundary clearly.

Equal ownership creates special problems. Two people own 50% each. They disagree. Now what? Some agreements give the CEO tiebreaking power for operational issues while requiring mediation for strategic deadlocks. Others mandate buy-sell triggers when impasse occurs.

Minority shareholders need information rights spelled out explicitly. Otherwise, they might only see annual financial statements state law requires. That's not enough to monitor your investment. Comprehensive rights include monthly financials, annual budgets, quarterly management updates, and reasonable access to corporate records.

The best way to predict the future is to create it.

— Peter Drucker

Financial Distribution Requirements

Majority shareholders can quietly exploit minorities through compensation games. They pay themselves $300,000 salaries while the business breaks even on paper. Result: working shareholders get rich, passive investors get nothing.

Distribution formulas prevent this. Document whether you'll make regular distributions, reinvest everything for growth, or split the difference. Be specific: "The company will distribute 35% of annual net income proportionally each January."

S-corporations and pass-through entities create tax obligations without cash distributions. You owe taxes on allocated income whether you actually receive money or not. Standard protection: require minimum annual distributions covering estimated tax liability at the highest marginal rate.

Missing these provisions entirely? That's how you end up with majority shareholders receiving $250,000 salaries while minority investors funded the whole operation and receive zero return for years.

How to Structure Voting Rights Provisions by Shareholder Class

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

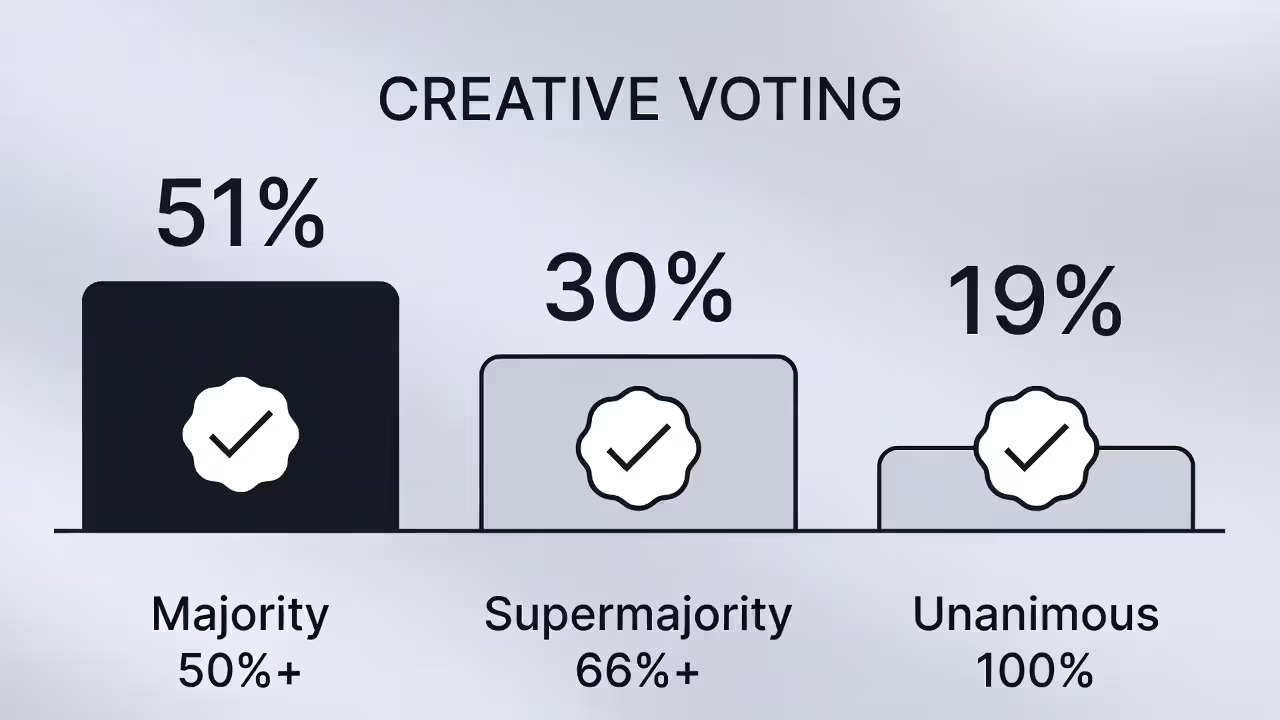

Simple majority rule sounds democratic until three shareholders with 51%, 30%, and 19% ownership realize the majority can do whatever they want. Forever.

Supermajority thresholds protect minorities by requiring broader consensus for major decisions. Set the threshold at 66%, and your 30% shareholder gains veto power. Raise it to 75%, and even the 19% shareholder can block problematic actions.

Different stock classes complicate voting math. Common shareholders might vote one way while preferred shareholders—typically investors—vote separately on specific issues. Series A preferred holders could demand their own class vote before the company issues Series B shares, preventing dilution without their consent.

Certain decisions justify unanimous consent requirements. Amending the shareholder agreement itself tops this list. Also: dissolving the company, fundamentally changing business purpose, or selling substantially all assets. These prevent 51% from rewriting the rules midstream.

Routine matters need simpler approval. Hiring employees, approving annual budgets under preset limits, opening bank accounts—simple majority suffices. Reserve supermajority for big stuff: issuing new shares, major acquisitions, debt exceeding certain thresholds.

| Decision Type | Majority Vote (50%+) | Supermajority (66-75%) | Everyone Agrees (100%) |

| Employee hiring | ✓ | ||

| Annual budgets | ✓ | ||

| New share issuance | ✓ | ||

| Company sale | ✓ | ||

| Agreement amendments | ✓ | ||

| Debt above $100K | ✓ | ||

| Business purpose changes | ✓ | ||

| New shareholder admission | ✓ |

Consider a practical scenario: Three shareholders own 50%, 30%, and 20%. Simple majority handles budgets and hiring. Supermajority at 66% means the two smaller shareholders together can block dilution. Unanimous consent protects everyone against forced sales or fundamental changes. This balances control with protection.

Veto rights work differently than voting thresholds. They give specific people power to block certain actions regardless of ownership percentage. A founder might retain veto power over acquisition offers even after dilution reduces their stake to 8%. Document exactly which decisions trigger vetoes and who holds them.

Ownership Transfer Clauses That Protect Existing Shareholders

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Nothing changes company dynamics like unwanted new shareholders. Transfer restrictions keep strangers out while preserving the business relationship you originally built.

Right of First Refusal vs. Right of First Offer

ROFR means this: Sarah wants to sell her shares. She finds an outside buyer willing to pay $500,000 on specific terms. Before closing that deal, she must offer existing shareholders the chance to match it. They get 30 days to decide. Match the terms, and Sarah sells to them instead. Decline, and she completes the outside sale.

ROFO flips the sequence. Sarah must offer her shares to existing shareholders first, at a price she sets. They review and decline. Only then can she shop for outside buyers—but she can't accept offers below what she offered internally.

Which approach works better? ROFR protects sellers by establishing market value through arms-length negotiations. ROFO protects existing shareholders by giving them first crack without competing against outside bids.

Most closely held corporations use ROFR. It feels fairer to selling shareholders who helped build the company. They're not locked into artificially low prices if existing shareholders lowball them.

Drag-Along and Tag-Along Rights Explained

Drag-along provisions let majority shareholders force minorities to join company sales. Here's why it matters: A buyer offers $10 million for 100% of the company. Great deal. But they won't buy 95%. They want everything or nothing. Without drag-along rights, a stubborn 5% shareholder can kill the transaction or extract inflated pricing.

Typical drag-along clauses require 66-75% shareholder approval to activate. Once triggered, holdouts must sell on identical terms as the majority. Same price per share, same payment structure, same representations and warranties.

Tag-along rights balance the equation. They let minorities join when majorities sell their stakes. The majority shareholder negotiates to sell their 60% stake for $8 million. Tag-along provisions allow the 40% minority to include their shares in the transaction at the same per-share price.

These rights create equilibrium. Majorities get exit flexibility. Minorities gain liquidity access. Both typically apply only to substantial transfers—like sales exceeding 50% ownership—not small transactions.

In matters of business, it is better to be precise than to be persuasive.

— Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Transfer Restrictions and Permitted Transfers

Blanket prohibitions on all transfers create problems for estate planning and family situations. Permitted transfers carve out reasonable exceptions without opening the floodgates.

Common exceptions: transfers to revocable living trusts, transfers between spouses (before divorce), transfers to children or trusts for their benefit, and transfers to heirs upon death. These allow normal life events without triggering buyout requirements.

But permitted transfers need limits. You might allow transfer to a spouse but require them to sign the shareholder agreement and be bound by its terms. Or permit trust transfers only if the shareholder remains trustee with voting control.

Buy-sell provisions create mandatory purchase obligations when specified events occur: death, permanent disability, bankruptcy, divorce, or employment termination. These prevent awkward situations like your co-founder's ex-spouse becoming a shareholder after their messy divorce.

Valuation formulas prevent $500,000 disagreements about what shares are worth. Options include: agreed-upon value updated annually, book value per latest financials, revenue multiples, EBITDA multiples, or independent appraisal. Each has tradeoffs.

Book value is simple but often undervalues growing companies. Revenue multiples work for consistent businesses but fluctuate for newer companies. Independent appraisals are accurate but expensive. Many agreements use book value for small transactions and appraisals for large ones.

Dividend Agreement Terms and Profit Distribution Rules

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

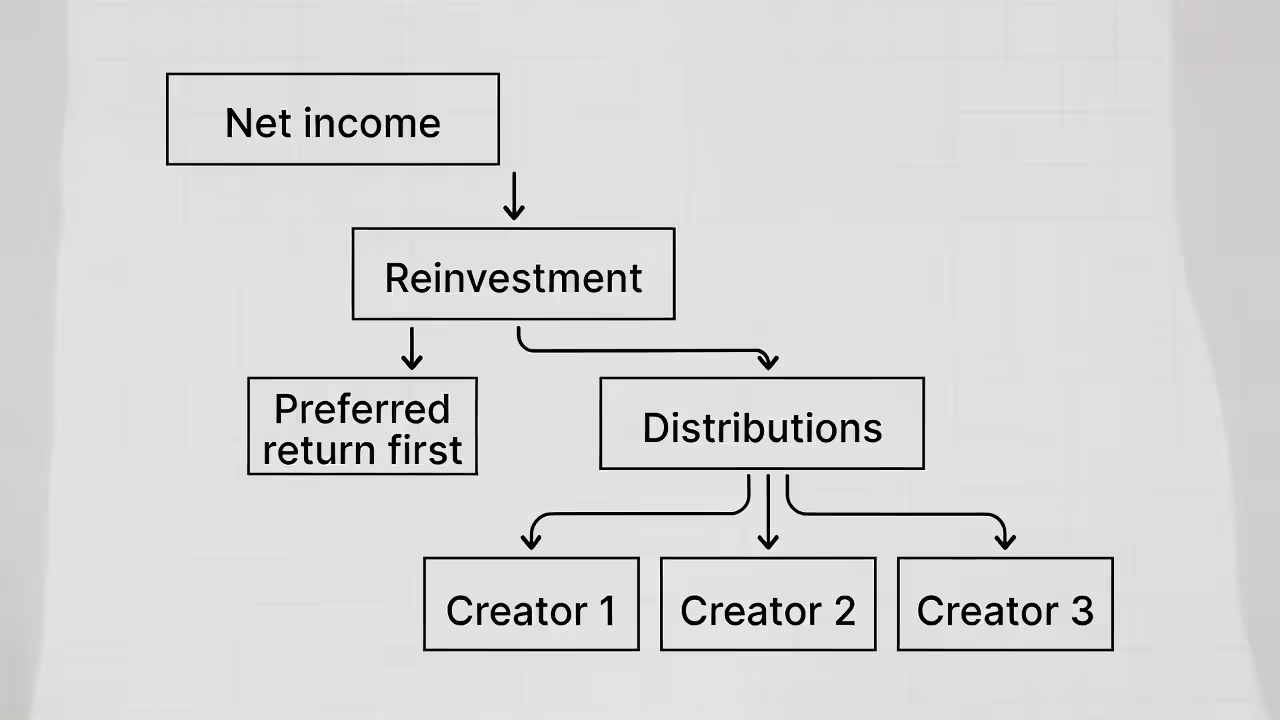

Distribution policies determine whether shareholders actually see returns or just own paper wealth. Without clear terms, majority shareholders controlling the board can hoard cash indefinitely while paying themselves generous salaries.

Mandatory distribution clauses require distributing a fixed percentage of profits. Common structure: distribute 40% of annual net income to shareholders, retain 60% for growth and working capital. This ensures some return while preserving operational flexibility.

Preferred returns give certain shareholders priority distributions before others receive anything. An investor might negotiate an 8% cumulative preferred return. They collect 8% annually on their investment before common shareholders get a penny. Miss a year? It accumulates.

Pass-through tax obligations create special problems. S-corporations and partnerships allocate taxable income to shareholders whether they receive cash or not. You could owe $30,000 in taxes on allocated income from a company that distributed nothing to you.

Standard protection: require annual distributions at least equal to the maximum federal and state tax rate multiplied by allocated income. If someone's allocated $100,000 and faces combined 40% tax rates, the company must distribute at least $40,000 for them to pay the tax bill.

Distribution timing affects both company cash flow and shareholder expectations. Quarterly distributions provide regular returns but strain working capital. Annual distributions give companies flexibility but test shareholder patience. Semi-annual splits the difference.

Consider different scenarios separately. Normal operations might use pro-rata distributions. Liquidation could prioritize preferred shareholders getting their investment back first, then common shareholders splitting what remains.

Governance Agreement Structure: Roles, Meetings, and Reporting

Governance provisions answer the boring questions that become critical during conflicts. Who sits on the board? How often do you meet? Who sees financial statements?

Board composition directly affects control. Three equal shareholders might each appoint one director. Alternatively, all shareholders vote on all directors, with cumulative voting protecting minority representation.

Here's how cumulative voting works: You own 30% of shares. Three board seats are being filled. You get to cast all your votes (30% times three seats) for any candidates. You could put all 90% of your voting power behind one candidate, guaranteeing them a seat even though you're a minority.

Officer appointments typically fall under board authority, but shareholder agreements can require shareholder approval for key positions. Some agreements mandate shareholder consent for hiring or firing the CEO while leaving CFO and COO decisions to the board.

Meeting frequency ensures regular communication without creating administrative burden. State law usually requires one annual shareholder meeting. Quarterly meetings provide better oversight for active shareholders. Specify whether telephonic or video meetings satisfy requirements or whether physical presence is mandatory.

Notice requirements prevent surprise votes. Standard provisions require 15-30 days written notice stating meeting date, time, location, and agenda. Emergency meetings might allow 5-day notice but require higher voting thresholds for any action taken.

Information rights give shareholders visibility into company performance. Basic provisions require annual audited financials and tax returns—usually what state law mandates anyway. Enhanced rights include monthly unaudited financials, quarterly management reports, annual budgets, and reasonable access to corporate books and records.

Minority shareholders especially need robust information rights since they typically lack board representation and can't access information directly. Without explicit provisions, they're stuck with whatever the majority decides to share.

Common Mistakes When Customizing a Shareholder Agreement Template

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

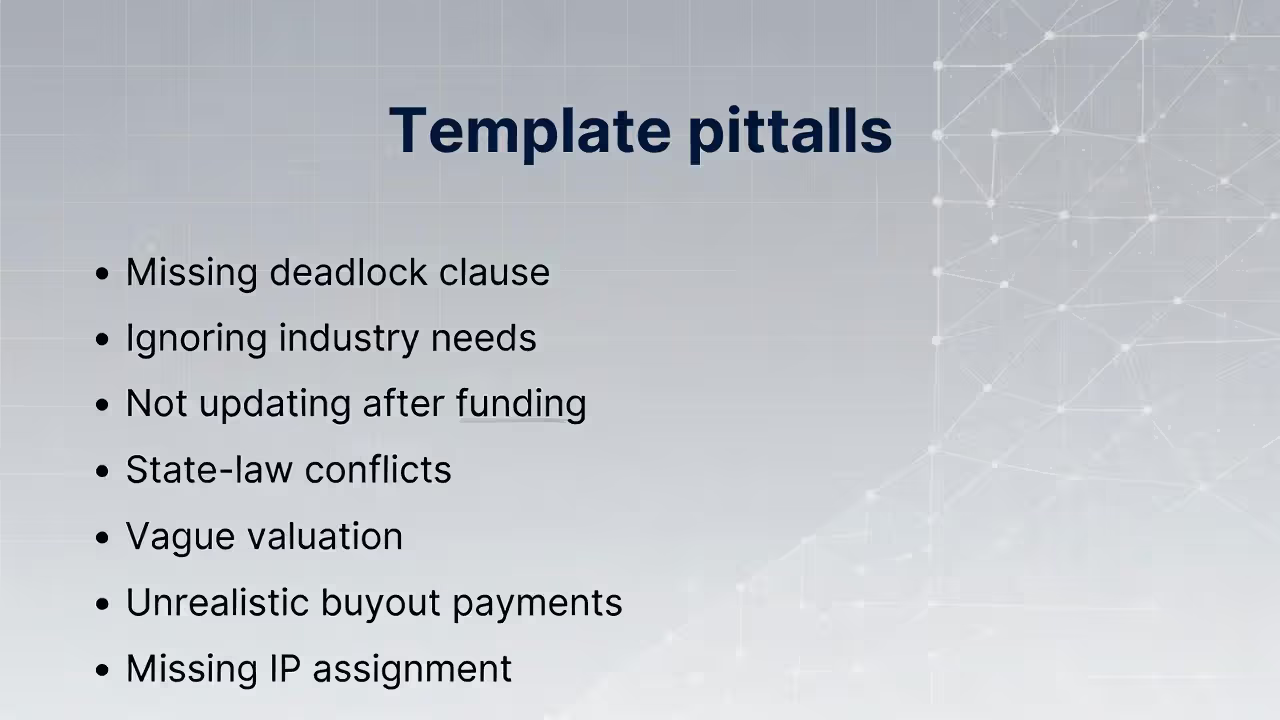

Templates provide helpful structure. They also create false confidence that checking boxes and filling blanks produces adequate protection.

Deadlock provisions get skipped constantly, usually because equal partners can't imagine disagreeing. Then they disagree. A 50-50 split without tiebreaking mechanisms creates paralysis. Neither shareholder can act unilaterally. Stalemate.

Effective deadlock solutions include: mandatory mediation, buy-sell triggers activated by deadlock, appointing an independent third director with tiebreaking authority, or shotgun clauses where one shareholder names a price and the other chooses to buy or sell at that price.

Industry-specific needs get ignored when using generic templates. Technology startups need intellectual property assignment clauses, confidentiality provisions, and equity vesting tied to continued service. Family businesses need succession planning, key person insurance provisions, and transfer restrictions preventing outside ownership.

Post-funding updates get forgotten. Your original three-founder agreement doesn't mention investors because you didn't have any. Two years later, Series A investors negotiate separate rights. Now you've got conflicting documents. Which prevails? Better: amend the original agreement incorporating all new terms into one comprehensive document.

State law compliance gets overlooked. California voids most non-compete agreements exceeding narrow limits. Delaware permits broad restrictions. Some states require specific language or disclosures for certain provisions. Research your jurisdiction's requirements before finalizing anything.

Valuation formulas for buy-sell provisions get left vague. "Fair market value" sounds reasonable until parties disagree about valuation methodology, discount rates, and whether to include minority discounts. Specify whether you're using book value, EBITDA multiples (at what multiple?), independent appraisal (who chooses the appraiser?), or agreed-upon values updated annually.

Payment terms for mandatory buyouts often assume unlimited company cash. Requiring immediate payment when a founder dies could bankrupt the company. Structure installment payments over 3-5 years with reasonable interest to preserve cash flow while fulfilling obligations.

Intellectual property ownership gets assumed rather than documented. Who owns code written by a founder before incorporation? Improvements made using company resources? Inventions created on personal time? Include explicit IP assignment provisions confirming all shareholder-created IP belongs to the company.

Frequently Asked Questions About Shareholder Agreements

Getting shareholder agreements right prevents the disputes that kill companies and friendships. Templates offer starting points, but thoughtful customization based on your specific ownership structure, business model, and shareholder relationships determines whether you've created real protection or just comforting paperwork.

Invest in proper documentation now. It's cheaper than litigation later. Treat your shareholder agreement as a living document that evolves with your business, not a one-time formality you file away after signing and never revisit.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on Legal Insights is provided for general informational purposes only. It is intended to offer insights, commentary, and analysis on legal topics and developments, and should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for professional consultation with a qualified attorney.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Laws and regulations may vary by jurisdiction and may change over time. The application of legal principles depends on specific facts and circumstances.

Legal Insights is not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content, or for any actions taken based on the information provided on this website. Users are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situation before making any legal decisions.