Two people signing a licensing agreement with sections for rights, territory, and royalties visible

Licensing Agreement Template: How to Draft IP Contracts That Protect Your Rights

One vague clause in your licensing agreement could sink your entire deal. I've seen business owners lose five-figure royalty streams because their contract said "reasonable use" instead of specifying exact parameters. And that's the mild scenario—worse cases involve losing IP rights completely or facing lawsuits from licensees who claim your ambiguous language gave them broader rights than you intended.

Here's what usually happens: You find a licensing agreement template online, plug in your details, sign it, and assume you're protected. Everything seems fine until month six when your licensee starts selling products in territories you never authorized. You pull out the contract, ready to enforce your rights, only to discover the geographic restrictions say "primarily in the United States"—language that could mean anything from 51% U.S. sales to 99% U.S. sales.

This breakdown covers the specific clauses, payment structures, and legal requirements that turn a generic template into an enforceable contract. You'll learn which terms courts actually uphold and which ones create more problems than they solve.

What Makes a Licensing Agreement Legally Binding

Courts look for three specific things before they'll enforce your licensing contract. First, both parties need to have entered the agreement willingly—no coercion, no misrepresentation, no confusion about what they're signing. If someone can prove they were pressured or misled, the entire agreement collapses.

Second, something of value must change hands. Usually that's money flowing from the licensee to you in exchange for IP rights, but it doesn't have to be cash. I've seen valid licensing agreements where the consideration was marketing services, cross-licensing of another patent, or even equity in the licensee's company. What matters is that each side gets something they value.

Third, the contract's purpose must be legal. You can't license IP to help someone violate copyright law or evade regulations. Sounds obvious, but I've reviewed agreements that inadvertently created illegal situations—like licensing software specifically to circumvent another company's technical protection measures.

The real enforceability issues come down to precision, though. A judge can't enforce terms that don't have clear meaning. When your contract says the licensee can use your trademark "as needed for promotional activities," what does that actually permit? Social media posts? Billboard advertisements? Television commercials? The licensee thinks it means all three; you think it means business cards and brochures. Without specific language, you're both right—which means you're headed for expensive litigation to figure out what you actually agreed to.

Who signs the agreement matters more than most people expect. Corporate employees can't always bind their companies to major contracts. That salesperson or department manager might lack signing authority for a $150,000 exclusive license. Before you rely on their signature, request documentation proving they have authority—board resolutions, corporate bylaws, or written authorization from officers. Discovering after the fact that your agreement isn't binding wastes everyone's time and money.

Get everything in writing. Yes, oral licensing agreements technically exist in some states, but proving what you agreed to becomes an expensive he-said-she-said battle. Most states require written contracts for agreements lasting over one year or involving substantial money through Statute of Frauds laws. Even when verbal agreements might be legal, written documentation prevents the relationship-destroying arguments about who promised what.

Core Components Every Licensing Agreement Must Include

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

These foundational sections need to appear in every licensing agreement template you use. Miss even one and you're creating risk.

Grant of Rights and Scope Limitations

The grant clause determines exactly which IP rights transfer to the licensee and which stay with you. Generic language like "Licensee receives rights to the Technology" accomplishes nothing useful. Which rights? Usage rights? Modification rights? Resale rights? Sublicensing rights?

Compare that vagueness to this: "Licensee receives non-exclusive, non-transferable rights to install and operate the Software on exactly seven workstations located at Licensee's Portland headquarters, solely for internal accounting purposes." Now nobody can claim confusion about whether the licensee can resell the software, let their Seattle office use it, or install it on laptop eight.

Geographic boundaries matter tremendously for brands and trademarks. Maybe you license your coffee shop brand for merchandise throughout California but keep Oregon, Washington, and all international markets for yourself. That preserves your expansion options while generating revenue from your existing territory.

Product category restrictions work the same way—authorize your brand on athletic apparel but explicitly prohibit use on electronics, food products, or medical devices. Licensees sometimes assume that paying for your brand gives them carte blanche to slap it on anything. Your contract needs to kill that assumption immediately.

Exclusivity determines whether you can license identical rights to competitors. Exclusive licenses cost more because the licensee gains market advantages—they're the only ones who can manufacture your patented device or use your trademarked brand in their industry. Non-exclusive licenses let you spread the same IP across multiple licensees simultaneously, multiplying your revenue. Semi-exclusive arrangements cap licenses at a specific number ("no more than three licensees in the automotive sector") or limit exclusivity to particular industries while keeping other markets open.

Clarity is the counterbalance of profound thoughts.

— Luc de Clapiers

Payment Terms and Royalty Structures

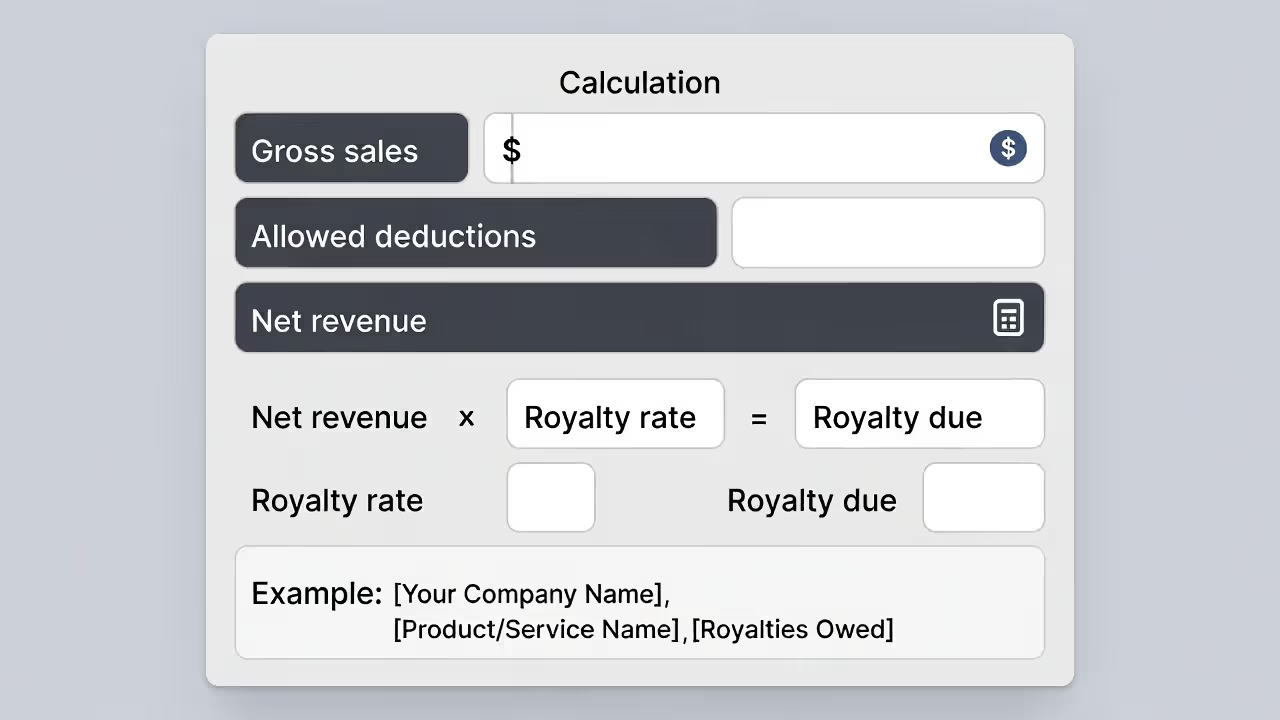

Money clauses need precision down to the payment method and currency denomination. Saying "Licensee pays royalties for IP use" provides zero useful information. Try this instead: "Licensee pays 8% of Net Revenue, defined as gross sales minus returns, discounts exceeding 15%, and applicable sales tax, via ACH transfer within 30 days following each calendar quarter's end."

Define every single financial term. What exactly counts as "revenue" in your agreement? Gross sales including shipping? Product sales only or also service fees? For patent licenses covering manufactured goods, do royalties apply when the licensee produces inventory or only when they sell it? These distinctions seem tedious until you're arguing about whether $35,000 in royalties is actually owed.

Minimum guarantees protect you when licensees acquire your IP but fail to exploit it aggressively. A clause requiring minimum annual royalties of $30,000 regardless of actual sales ensures compensation even when the licensee barely markets your brand or sits on your patent to block competitors. This provision also incentivizes active commercialization—if they're paying $30,000 anyway, they might as well generate enough sales to make it worthwhile.

Your payment schedule should match the underlying business model. Monthly payments suit subscription software where revenue is steady and predictable. Quarterly payments work for most product royalties—frequent enough to track performance without creating administrative nightmares. Annual payments make sense for low-volume, high-value items or stable long-term relationships. Whatever schedule you pick, nail down specific due dates ("the 15th of the month following quarter end") and late payment penalties—1.5% monthly interest is standard, though some industries use higher rates.

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Duration and Termination Provisions

License duration falls into three categories: fixed-term, perpetual, or milestone-based. Fixed-term agreements ("This license terminates December 31, 2027") provide certainty for both parties but require renegotiation as expiration approaches. Perpetual licenses continue indefinitely, which sounds appealing but requires robust termination clauses for when relationships sour. Milestone-based terms ("This license continues through the patent's legal life, ending when the patent expires or is invalidated") tie the agreement to the IP's actual protection period.

Termination clauses need coverage for both "with cause" and "without cause" scenarios. For-cause termination lets you end the agreement immediately when the licensee commits material breaches—stops paying, uses your IP beyond authorized scope, files for bankruptcy, or violates confidentiality provisions. Without-cause termination (sometimes called convenience termination) lets either party exit healthy relationships that simply aren't working out anymore, usually requiring 60-90 days' advance notice.

Post-termination obligations prevent the chaos that erupts when agreements end. Require the licensee to immediately cease all IP use, return or destroy any confidential materials you've shared, submit final royalty payments with supporting documentation, and sometimes continue selling existing inventory during a defined wind-down period (typically 30-90 days). Without these provisions spelled out, former licensees keep using your trademark or manufacturing your patented products while you scramble to get court orders stopping them.

Automatic renewal clauses keep successful relationships going without constant renegotiation overhead. "This agreement automatically renews for successive one-year terms unless either party provides 60 days' written notice of non-renewal before the current term ends" works beautifully when both parties benefit from continuity.

In business, the biggest risk is not taking any risk — but the second biggest is not defining it.

— Peter Drucker

Intellectual Property License Clauses That Prevent Disputes

These protective clauses separate professional contracts from amateur ones. They address the real-world problems that emerge months or years after signing, when business realities collide with legal theory.

Indemnification clauses determine who pays legal bills when IP infringement claims surface. Imagine you license a patent to a manufacturer, and six months later a competitor sues them claiming the patent infringes their earlier patent. Who pays the defense costs? Standard indemnification provisions make the licensor responsible for defending the IP's validity ("Licensor will defend any claims that the licensed patent infringes third-party rights and cover resulting costs") while the licensee bears liability for uses outside authorized scope.

Quality control provisions become critically important for trademark licensing. If you license your brand without maintaining control over quality, courts may rule you've committed "naked licensing"—essentially abandoning your trademark through neglect. Include specific quality benchmarks, approval rights over products or marketing materials, and inspection rights with defined notice periods. A restaurant brand licensing its name for packaged foods might require: "All products must meet quality specifications in Exhibit A; Licensor may inspect manufacturing facilities and review quality control records with 72 hours' advance notice."

Confidentiality clauses safeguard trade secrets and proprietary information shared during the relationship. Software licenses often involve sharing source code or technical architecture documentation. Manufacturing licenses might require disclosing proprietary processes or formulas. These confidentiality obligations should explicitly survive termination—the licensee can't exploit your confidential information to compete after the license ends.

Sublicensing restrictions prevent your licensee from effectively becoming your competitor by granting rights to third parties. Unless you explicitly permit sublicensing, licensees shouldn't have authority to grant any rights to others. Even when you allow sublicensing, retain approval rights over sublicensees and require them to follow identical terms as your original agreement.

Warranty provisions establish expectations about the IP's condition and fitness. Most licensors offer limited warranties—they own the IP, it doesn't infringe third-party rights, they have authority to grant the license—while disclaiming broader promises about merchantability or fitness for specific purposes. This protects you when the licensee's business model fails or your IP doesn't solve their particular problem as hoped.

Audit rights let you verify reported royalties match actual sales. "Licensor may audit Licensee's financial records related to this agreement once per calendar year, providing 30 days' written notice, during normal business hours at Licensee's principal place of business" is standard language. Include a provision requiring the licensee to cover audit costs if the audit reveals underpayment exceeding 5% of amounts due—this incentivizes accurate reporting while preventing you from bearing costs when licensees cheat.

How to Structure Royalty Payments in Your Agreement

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

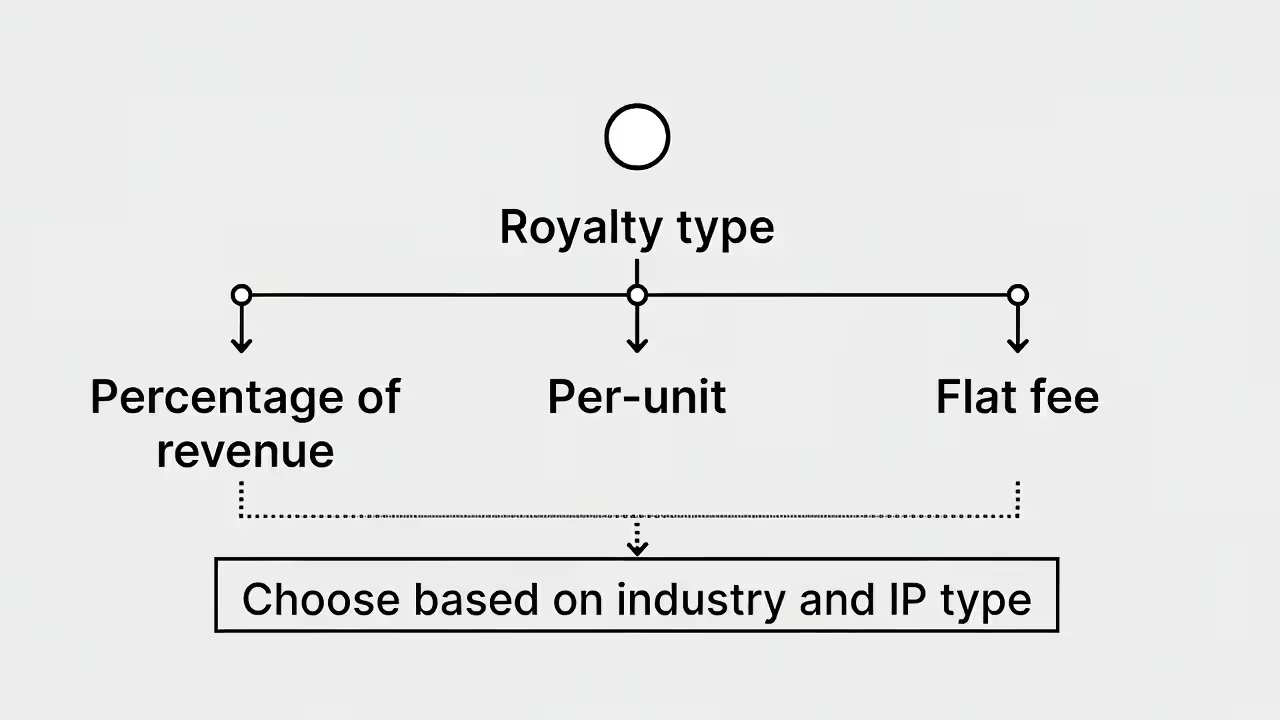

Royalty structures vary dramatically based on industry standards, IP type, and which party has more negotiating leverage. Choose the wrong structure and you either leave money on the table or make the license economically impossible for the licensee.

Percentage-based royalties connect payment directly to the licensee's commercial success. Software licenses commonly command 5-15% of revenue depending on the software's role in the licensee's offering. Patent licenses for manufactured goods typically extract 2-10% depending on how essential the patent is to the final product's value. Book publishing has traditionally paid authors 10-15% of cover price. These percentages reflect decades of industry practice, but your specific rate depends on exclusivity, the IP's competitive advantage, and how much work the licensee must invest to commercialize it.

How you define revenue matters as much as the percentage itself. Gross revenue maximizes your income but may price out potential licensees with thin margins. Net revenue (gross sales minus returns, discounts, and sometimes specific expenses) is far more common in practice. Nail down exactly which deductions you'll allow. A software licensor might accept deductions for sales tax and payment processing fees but reject deductions for marketing spend, overhead allocation, or "administrative costs."

Flat-fee structures deliver predictable income independent of the licensee's sales performance. A one-time payment of $75,000 for a perpetual, non-exclusive license works when both parties value simplicity and you don't want to track sales. Annual flat fees ($15,000 per year for five years) spread payments across time while maintaining predictability for both parties.

Per-unit royalties make sense for physical products with clear unit economics. "$3.50 per unit manufactured" works perfectly for patented manufacturing processes or licensed characters on merchandise. This structure aligns tightly with actual usage and verification is straightforward through production records or shipping manifests.

Hybrid models combine approaches for optimal risk-sharing between parties. One common structure pairs an upfront payment with ongoing percentage royalties: "$40,000 upon execution plus 6% of Net Revenue paid quarterly." This gives you immediate compensation while preserving upside potential if the licensee succeeds. Another hybrid uses tiered percentages that escalate with volume: "5% on annual sales up to $500,000, 7% on sales from $500,001 to $1 million, and 10% on sales exceeding $1 million." This rewards successful commercialization while going easier on licensees in early stages.

Minimum guarantees shield you from licensee underperformance. Even with percentage royalties, you can require minimum annual payments regardless of sales. If the licensee pays 8% of sales but guarantees $50,000 annually, they owe $50,000 even if 8% of their actual sales only equals $38,000. This structure creates powerful incentives for licensees to actively exploit your IP rather than sitting on it.

Payment timing significantly affects your cash flow. Monthly payments provide steady income but multiply administrative burden for both parties. Quarterly payments hit the sweet spot for most agreements—frequent enough to stay connected to performance, infrequent enough to minimize overhead costs. Annual payments only make sense for stable, mature relationships where both parties trust each other completely.

Reporting requirements should accompany every royalty structure you implement. Require detailed sales reports with each payment showing units sold or services rendered, revenue generated, deductions taken, and royalty calculations. Specify the exact report format to simplify verification. "Licensee submits quarterly reports using the template in Exhibit B within 15 days of quarter end, followed by payment within 30 days of quarter end" eliminates ambiguity about expectations.

Comparison of Common Royalty Payment Structures

| Structure Type | How It Works | Pros | Cons | Best For |

| Flat Fee | Single payment or recurring fixed amount regardless of licensee's sales performance | Income is predictable; minimal administrative work; no sales tracking needed | You miss out if product becomes wildly successful; difficult to negotiate fair amount upfront; may undervalue your IP | Mature IP with established market value; licensors prioritizing simplicity over upside; situations where tracking sales is impractical or impossible |

| Percentage of Revenue | Payment calculated as specified percentage of licensee's sales (typically 5-15%) | Your income grows with licensee's success; creates aligned incentives; reflects IP's actual contribution to value | Requires continuous sales tracking and potential auditing; cash flow depends entirely on licensee performance; frequent disputes over revenue calculation | Most commercial licensing situations; cases where IP significantly impacts product value; long-term relationships with mutual trust |

| Per-Unit Royalty | Fixed dollar amount paid for each unit manufactured, sold, or distributed | Easy to calculate and verify through production records; directly ties payment to usage; fair across different price points | Ignores revenue variations if licensee discounts heavily; requires accurate unit tracking; can disadvantage licensees with low margins | Physical products with clear unit definitions; manufacturing licenses; merchandise featuring licensed characters or brands |

| Hybrid Model | Combines upfront payment with ongoing royalties, or uses volume-based tiered percentages | Balances risk between both parties; provides immediate and future compensation; can incentivize growth through tiers | More complex administration and accounting; requires careful structural design; greater potential for disputes over terms | High-value IP with uncertain market potential; new market entries; situations requiring guaranteed baseline payment plus upside participation |

5 Critical Mistakes That Invalidate Licensing Contracts

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

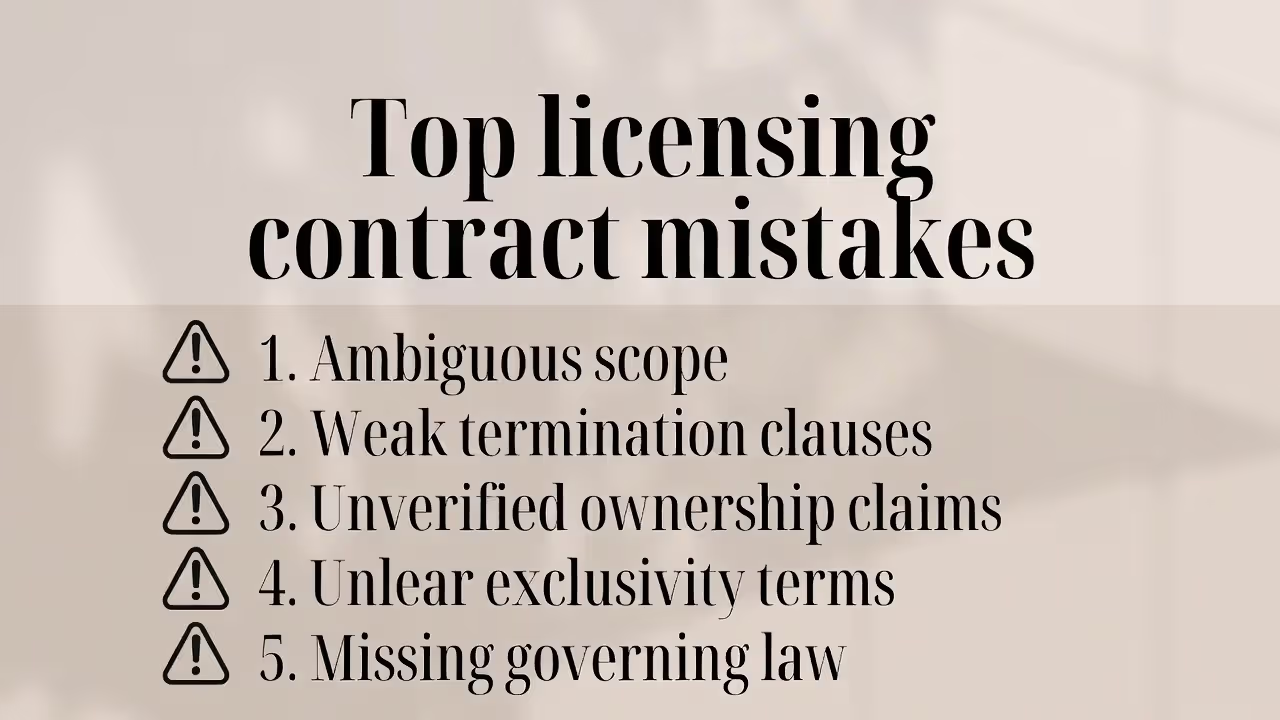

1. Ambiguous Scope That Nobody Can Enforce

Contracts stating "Licensee may use the trademark for promotional activities" fail in court because "promotional activities" lacks objective meaning. Business cards? Social media campaigns? Stadium naming rights? One software company licensed its code for "customer integration projects" only to find the licensee reselling it as a standalone product to hundreds of clients. The court couldn't determine whether this violated the agreement because "integration projects" could reasonably include that use. Fix this by listing exactly what's permitted and explicitly prohibiting everything else. "Licensee may use the trademark exclusively on product packaging, in-store displays, and the product detail pages on Licensee's e-commerce website; all other uses including social media, television, radio, and print advertising require separate written approval" eliminates interpretation games.

2. Missing or Unenforceable Termination Clauses

Agreements lacking clear termination provisions trap both parties in failing relationships indefinitely. Even worse, heavily one-sided termination clauses often get thrown out by courts. A clause allowing the licensor to "terminate immediately at any time for any reason without notice or cause" likely gets struck down as unconscionable. Build balanced termination rights instead: immediate termination for material breach (non-payment, unauthorized uses beyond scope, bankruptcy filing), termination with 30-day cure period for correctable breaches (late reporting, minor quality control failures), and mutual right to terminate without cause with 60-90 days' advance notice. This protects both parties while remaining enforceable.

3. Inadequate IP Ownership Verification

Licensing IP you don't actually own completely creates catastrophic liability exposure. A manufacturer paid $150,000 upfront to license a "patented" manufacturing process, then invested $800,000 in specialized equipment. Eighteen months later they discovered the patent application had been rejected—no patent ever existed. The manufacturer sued and recovered not just their $150,000 but also their equipment costs, lost profits, and attorney fees. Before licensing anything, verify ownership through USPTO records for patents, trademark database searches, copyright office registrations, or complete chain-of-title documentation for other IP. Include these representations in your agreement: "Licensor represents and warrants that it owns all rights, title, and interest in the Licensed IP, free from any liens, encumbrances, or third-party claims, and possesses full authority to grant this license."

4. Unclear Exclusivity Terms That Create Conflicts

Exclusivity disputes routinely destroy licensing relationships and spawn expensive litigation. A licensee pays premium rates expecting "exclusive rights" but six months later discovers the licensor has licensed identical rights to a direct competitor. The licensee sues, arguing exclusivity meant sole rights in their entire market. The licensor counters that exclusivity only applied to a specific product subcategory. Both interpretations seem reasonable given the vague language, so the case drags on expensively. Define exclusivity with surgical precision: "Licensor grants Licensee exclusive rights to use the Patent for manufacturing automotive brake components sold in North America; Licensor explicitly retains rights to license the Patent for non-automotive applications worldwide and for automotive applications outside North America."

5. Jurisdiction and Governing Law Failures

Forgetting to specify jurisdiction and governing law transforms disputes into procedural nightmares before you even address the actual disagreement. A California licensor and New York licensee sign an agreement with no governing law provision. When disputes erupt, they burn through months and tens of thousands in legal fees arguing about which state's law controls before tackling the substantive issues. International licenses magnify this problem exponentially—countries have radically different IP laws, enforcement mechanisms, and attitudes toward licensing restrictions. Every agreement needs this: "This Agreement is governed by the laws of the State of Delaware, excluding its conflict of law principles. Both parties consent to exclusive jurisdiction in state and federal courts located in New Castle County, Delaware, and waive any objections to venue or personal jurisdiction in those courts."

Licensing Agreement Templates by Industry Type

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

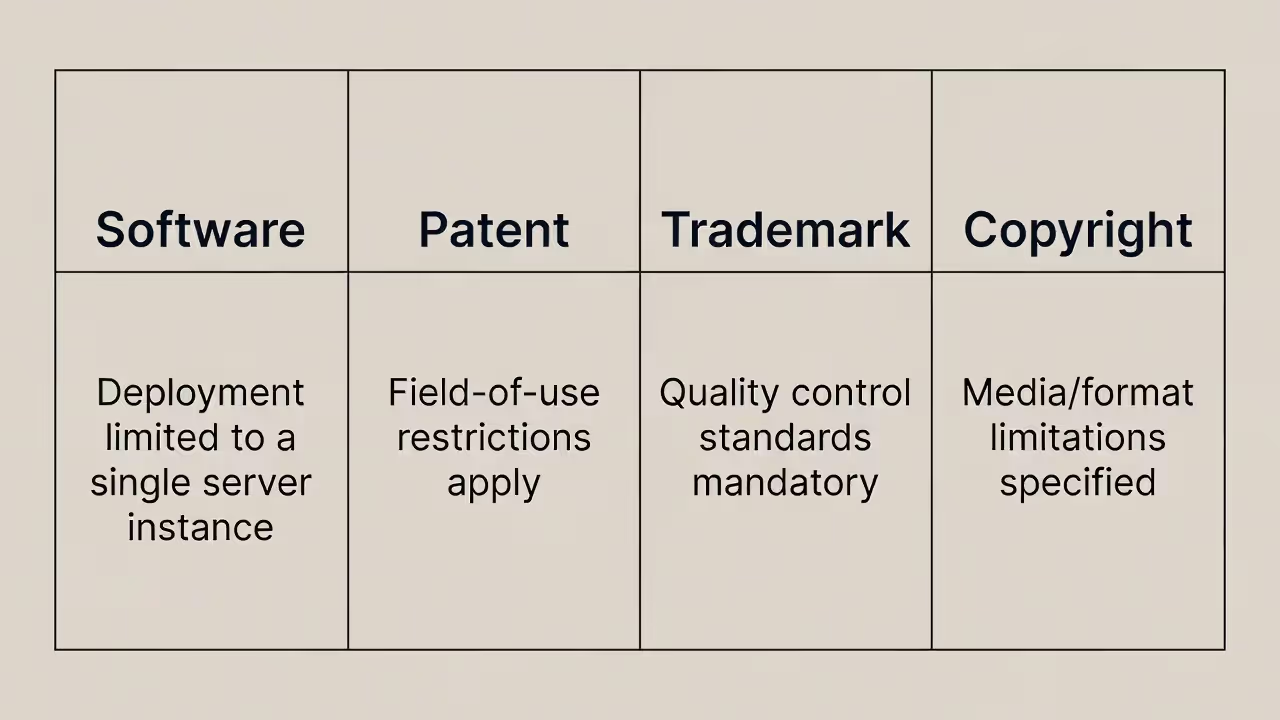

Different IP categories require fundamentally different contractual approaches. Software licenses look nothing like trademark licenses because the underlying rights, commercial risks, and business models differ completely.

Software and Technology Licenses

Software licensing agreements emphasize usage restrictions and technical deployment limitations. The grant clause typically specifies installation parameters (number of devices, concurrent users, named users, or enterprise-wide deployment), modification rights (can the licensee alter source code or customize the interface?), and distribution rights (strictly internal use or external distribution to customers allowed?).

Software licenses typically include extensive "as-is" warranty disclaimers with strict liability caps because software complexity makes guaranteeing bug-free operation essentially impossible. Standard clause: "Software is provided 'as is' without warranties of any kind, express or implied. Licensor's total liability under this agreement shall not exceed the fees Licensee paid during the twelve months immediately preceding the claim, regardless of the legal theory asserted."

Maintenance and support terms require explicit definition. Does the licensor provide software updates? Bug fixes? Security patches? Technical support via phone or email? For how long? At what additional cost? Many software licenses separate the initial license fee from ongoing annual maintenance: "$75,000 initial license fee plus annual maintenance at 20% of license fee ($15,000 annually) covering all updates, patches, and email support with 48-hour response times."

Patent Licenses

Patent licenses authorize the licensee to make, use, sell, offer for sale, and import inventions covered by specifically identified patents. The scope must list patents by their official USPTO numbers and clearly state whether the license covers only existing issued patents or extends to pending applications and future improvements.

Field-of-use restrictions are standard practice in patent licensing. A pharmaceutical patent might get licensed exclusively to one company for human therapeutics while being licensed non-exclusively to another for veterinary applications, maximizing the patent's revenue across distinct markets without creating competition.

Patent licenses frequently include diligence requirements forcing licensees to actively commercialize the invention rather than acquiring it solely to block competitors. "Licensee must invest minimum $750,000 in product development and regulatory approvals within eighteen months of execution and must launch commercial sales within thirty-six months" creates concrete commercialization obligations with measurable milestones.

Trademark and Brand Licenses

Trademark licenses require extensive quality control provisions to maintain brand value and prevent courts from finding trademark abandonment through inadequate licensor oversight. You must maintain meaningful control over how licensees use your mark, including product quality specifications, packaging design standards, and marketing message guidelines.

These agreements typically require licensees to submit product samples, packaging designs, and marketing materials for advance approval. "Licensee must submit three pre-production samples to Licensor for quality approval before commencing manufacturing; Licensor will approve, request modifications, or reject within ten business days of receipt."

Trademark licenses must explicitly address goodwill ownership—all goodwill generated through the licensee's use of your mark must accrue to you as the licensor. This preserves your trademark's value and prevents licensees from claiming ownership rights based on marketing investments they made.

Creative Works and Content Licenses

Author: Rachel Holloway;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

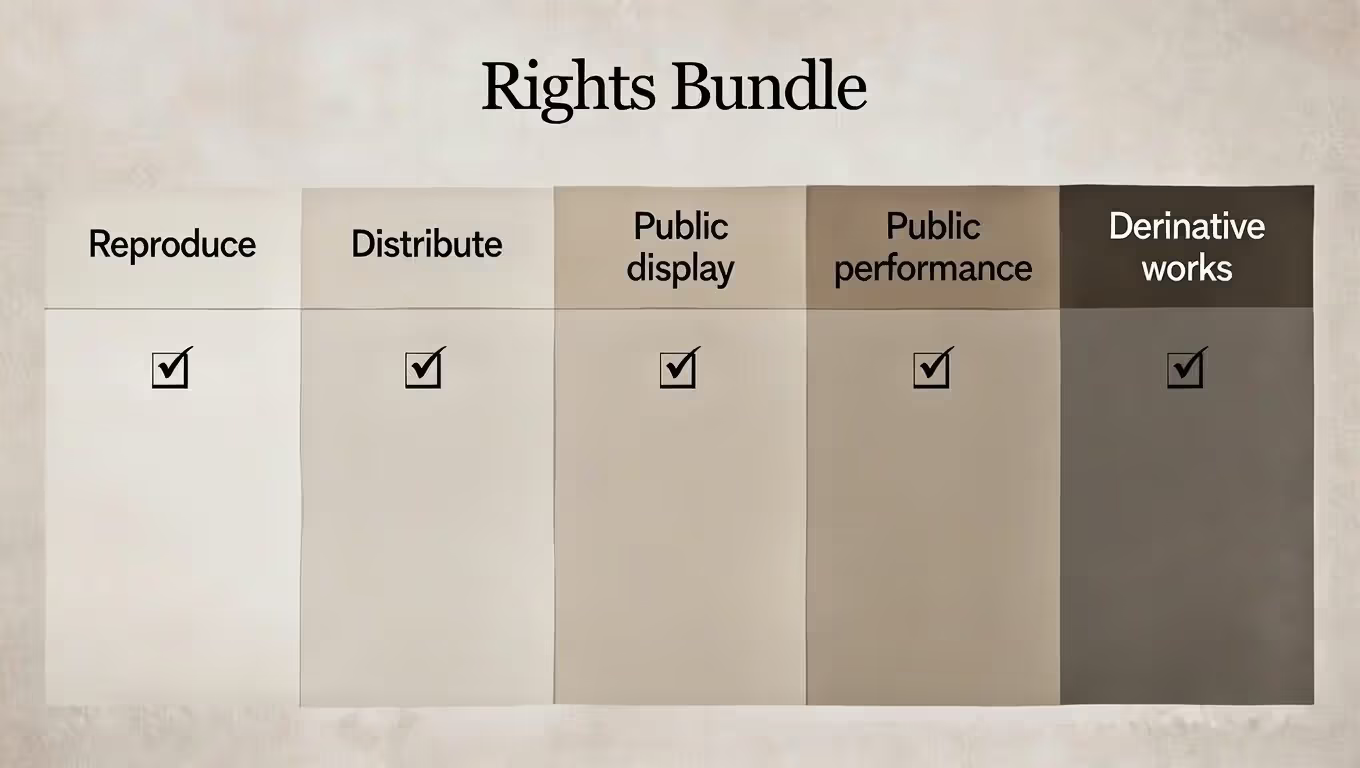

Copyright licenses for creative content—articles, photographs, music, video footage—focus on granting specific bundle of rights from the complete copyright. The grant might permit reproduction, distribution, public display, public performance, and derivative works creation, or it might cherry-pick specific rights while reserving others.

Media and format restrictions are essential in content licensing. A photographer might license an image for print magazine use but prohibit digital media, or authorize use in North America while reserving international rights. "Licensor grants Licensee non-exclusive rights to reproduce the Photograph in print magazines and catalogs distributed in the United States and Canada for twelve months from execution" defines scope precisely without ambiguity.

Attribution and moral rights clauses protect the creator's reputational interests beyond economic compensation. Many creative professionals require credit lines: "Licensee must include photo credit reading 'Photography ©

' immediately adjacent to or below each reproduction of the Photograph in at least 8-point font." Some jurisdictions recognize moral rights preventing modification or use in contexts that damage the creator's reputation.Key Clause Differences Across License Types

| Software License | Patent License | Trademark License | Copyright License | |

| Grant of Rights | Installation, execution, modification, and distribution rights for software code and associated documentation | Right to make, use, sell, offer for sale, and import inventions covered by specifically identified patents | Right to use brand names, logos, designs, and marks on specified products, services, or marketing materials | Right to reproduce, distribute, publicly display, publicly perform, or create derivative works from creative content |

| Typical Duration | 1-3 year terms with renewal options, or perpetual licenses with ongoing maintenance fees | 10-20 years or until patent expiration, whichever occurs first | 3-10 years with renewal contingent on quality maintenance and brand standards compliance | Highly variable: single-use licenses, fixed terms of 1-5 years, or duration of copyright term depending on use |

| Quality Control Requirements | Performance benchmarks, security standards, uptime guarantees, compatibility requirements | Manufacturing specifications, testing protocols, regulatory compliance standards, defect rate limits | Detailed product quality standards, packaging approval rights, facility inspection rights, brand guideline compliance | Attribution requirements, modification limitations, usage context restrictions, reputational protection clauses |

| Sublicensing Rules | Generally prohibited without explicit written consent; SaaS models may permit end-user sublicenses with restrictions | Usually prohibited or limited to specific fields of use; requires advance approval with flow-through of all terms | Tightly controlled or outright prohibited; advance approval required to prevent brand dilution and loss of control | Varies by license type; commercial uses typically prohibit sublicensing while editorial licenses may allow with restrictions |

| Primary Restrictions | Device limits, user caps, geographic boundaries, internal-use-only provisions, reverse engineering prohibitions | Field-of-use restrictions, geographic territories, production volume caps, manufacturing location limits | Product categories, quality benchmarks, geographic territories, exclusive versus non-exclusive status, approved vendors | Media formats, geographic territories, duration limits, modification rights, commercial versus non-commercial use distinctions |

| Termination Triggers | Non-payment, unauthorized copying or distribution, breach of user limitations, bankruptcy, security breaches | Non-payment, failure to meet diligence milestones, patent invalidation, material quality breaches | Quality control failures, unauthorized product categories, brand damage incidents, non-payment, unapproved sublicensing | Unauthorized uses beyond scope, exceeding licensed rights, non-payment, modifications causing creator reputational harm |

Frequently Asked Questions About Licensing Agreements

Your licensing agreement template only protects you as well as the thought you invest in customizing it for your specific situation. The clauses, structures, and provisions outlined here create the framework for enforceable contracts that protect your IP while enabling profitable licensing relationships.

Start by defining scope with surgical precision that eliminates interpretation games. Structure royalty payments to align both parties' incentives toward successful commercialization. Build in protective clauses covering indemnification, quality control, and confidentiality. Specify balanced termination rights that let you exit bad relationships without burning through legal fees. Choose governing law and jurisdiction that favor practical enforcement.

Most importantly, treat licensing agreements as living documents that should evolve with your business rather than static forms you sign once and forget. Review them annually, particularly when renewals approach. Market conditions that made sense three years ago might look completely different today—competitive dynamics shift, your IP's value increases, industry royalty rates change. Successful licensors treat their agreements as strategic assets requiring the same ongoing attention as the IP itself.

The gap between a solid licensing agreement and a weak one usually comes down to specificity. Every vague term becomes a future dispute waiting to erupt. Every undefined term becomes an argument you'll have later when stakes are higher. Every missing protective clause represents protection you've voluntarily given up. Invest the time upfront to nail down the details, and your licensing agreements will generate sustainable revenue while protecting your most valuable assets—your intellectual property rights.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on Legal Insights is provided for general informational purposes only. It is intended to offer insights, commentary, and analysis on legal topics and developments, and should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for professional consultation with a qualified attorney.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Laws and regulations may vary by jurisdiction and may change over time. The application of legal principles depends on specific facts and circumstances.

Legal Insights is not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content, or for any actions taken based on the information provided on this website. Users are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situation before making any legal decisions.