Remedies start with proof of breach and loss

Remedies in Contract Law: Your Complete Guide to Legal Options After a Breach

Someone just backed out of your contract. Now what?

The law gives you several paths forward, but they're not all available in every situation. Getting the right remedy means understanding which option matches your specific circumstances—and what evidence you'll need to convince a judge. Courts won't simply hand you whatever you ask for. They'll examine what you've lost, what you could have prevented, and whether the contract itself limits your options.

The fundamental goal? Putting you back where you'd be if the other party had actually kept their word. Sounds simple enough. The tricky part comes when you try proving exactly where that is. Your email threads, invoices, and financial records become crucial. Most cases settle without ever seeing a courtroom, but knowing what a judge would likely award gives you serious leverage during negotiations.

What Are Contract Remedies and When Do They Apply?

Think of contract remedies as the legal tools available once someone breaks a binding agreement. You can't just claim a remedy exists, though. First, you'll need to prove three things: a valid contract was formed, the other party breached their obligations, and you actually got hurt financially.

Valid contracts need four elements working together—an offer, acceptance, something of value exchanged, and both sides intending legal consequences. The breach needs to matter, too. Not every tiny deviation destroys a contract. Your contractor finishing two days behind schedule while delivering otherwise perfect work? You're looking at minimal damages, if any. That same contractor walking off the job halfway through? Now you've got grounds for substantial remedies.

Here's something people forget: you need clean hands. Courts won't help if you failed to pay as agreed or somehow caused the breach yourself. You'll also need proof that you upheld your obligations under the agreement.

There's another requirement that trips people up—the duty to mitigate. After someone breaches, you can't just sit back and watch damages pile up. The law expects reasonable efforts to minimize your losses. What counts as "reasonable" depends on your situation, but the principle stays constant.

Contract remedies overview breaks into three main buckets: monetary compensation (the most common), court orders requiring specific actions (rare but powerful), and restitution (getting back what you already gave). Each serves a distinct purpose and comes with its own set of rules.

Expectation Damages: Making the Non-Breaching Party Whole

Expectation damages meaning boils down to this: the court calculates what you'd have if the contract had been performed properly, then awards you the difference. This is what judges default to in most breach cases. The goal isn't punishing the other side—it's compensating your actual economic loss.

Damages are meant to place the injured party in as good a position as if the contract had been performed

— Restatement (Second) of Contracts

Start with the benefit of your bargain. You contracted to purchase commercial property for $500,000, but it's actually worth $600,000? Your expectation damages hit $100,000—the profit that vanished when the seller refused to close. You hired a web developer for $10,000, then had to pay someone else $15,000 for identical work? You recover that $5,000 difference, plus any direct costs from the delay.

Courts split expectation damages into two categories. Direct damages flow naturally and immediately from the breach itself. Consequential damages are the ripple effects—but only if they were reasonably foreseeable when you made the contract. Your supplier's late delivery tanks a major sales event? Those lost profits might qualify as consequential damages, assuming the supplier knew about that deadline when agreeing to your delivery schedule.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

How Courts Calculate Expectation Damages

The formula looks straightforward: value you should have received minus value actually received, plus additional costs incurred from the breach. Reality gets messy. You must prove each element with reasonable certainty—speculation doesn't cut it. Claiming lost business profits? Better bring financial records, market analysis, or expert testimony showing what you would have earned.

New businesses face steeper hills here. A startup claiming $200,000 in year-one profits needs more than rosy projections. You'll need comparable business data, detailed business plans, and concrete evidence supporting those numbers. Established businesses can point to historical performance and existing customer contracts.

Courts also subtract costs you avoided because of the breach. A venue cancels your event contract? Your damages equal what you paid minus what you saved by not providing catering, staffing, and other planned expenses. You don't get to keep both the refund and the money you didn't have to spend.

Limitations and Caps on Expectation Awards

Even when breach is crystal clear, several legal doctrines can limit expectation damages. The foreseeability rule—established way back in 1854 with Hadley v. Baxendale—prevents recovery for losses the breaching party couldn't reasonably anticipate. Failed to mention special circumstances making the contract unusually valuable to you? Those extraordinary losses won't be covered.

The certainty requirement blocks speculative damages. Courts want evidence, not possibilities. You can't claim damages for a "potential" business opportunity that "might" have succeeded. This doesn't mean you need mathematical perfection—reasonable estimates backed by solid evidence work fine—but vague assertions go nowhere.

Sometimes contracts include liquidated damages clauses setting a predetermined breach amount. Courts enforce these when they represent a reasonable forecast of actual harm. The amount needs to make sense, though. A $50,000 penalty for being one day late on a $5,000 contract? Judges will toss that out as an unenforceable penalty clause.

Author: Foreseeability and certainty can cap awards.;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Reliance Damages vs. Expectation Damages: Which One Applies?

Reliance damages explained: instead of compensating the profit you expected, this remedy reimburses expenses you incurred because you trusted the contract would be performed. When expectation damages prove too speculative, reliance damages offer a backup option.

Picture this: you hire a keynote speaker for your conference. You rent a bigger venue, print promotional materials featuring their name, and sell premium-priced tickets based on their appearance. They cancel. Your expectation damages would be the extra revenue their presence would have generated—good luck proving that precisely. Reliance damages? Those cover the venue upgrade cost, printing expenses, and other money you spent because you believed they'd show up.

You can't collect both expectation and reliance damages for the same breach. They're alternatives, not add-ons. Plaintiffs typically pick reliance when they can't demonstrate the contract would have been profitable. A new restaurant concept might recover its buildout costs and initial inventory expenses through reliance damages even without proving future success.

Here's the key distinction: expectation damages look forward to benefits you lost. Reliance damages look backward at costs you incurred. Courts require proof that your reliance made sense and that expenses were actually caused by the contract. Money you'd have spent anyway doesn't count.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

One strategic wrinkle: reliance damages can sometimes exceed expectation damages, but courts may cap recovery at what you'd have gained from full performance. You spent $100,000 preparing for a contract that would have netted only $60,000 profit? Some jurisdictions limit reliance recovery to $60,000. Others allow full recovery, reasoning the breaching party shouldn't benefit from your poor bargain.

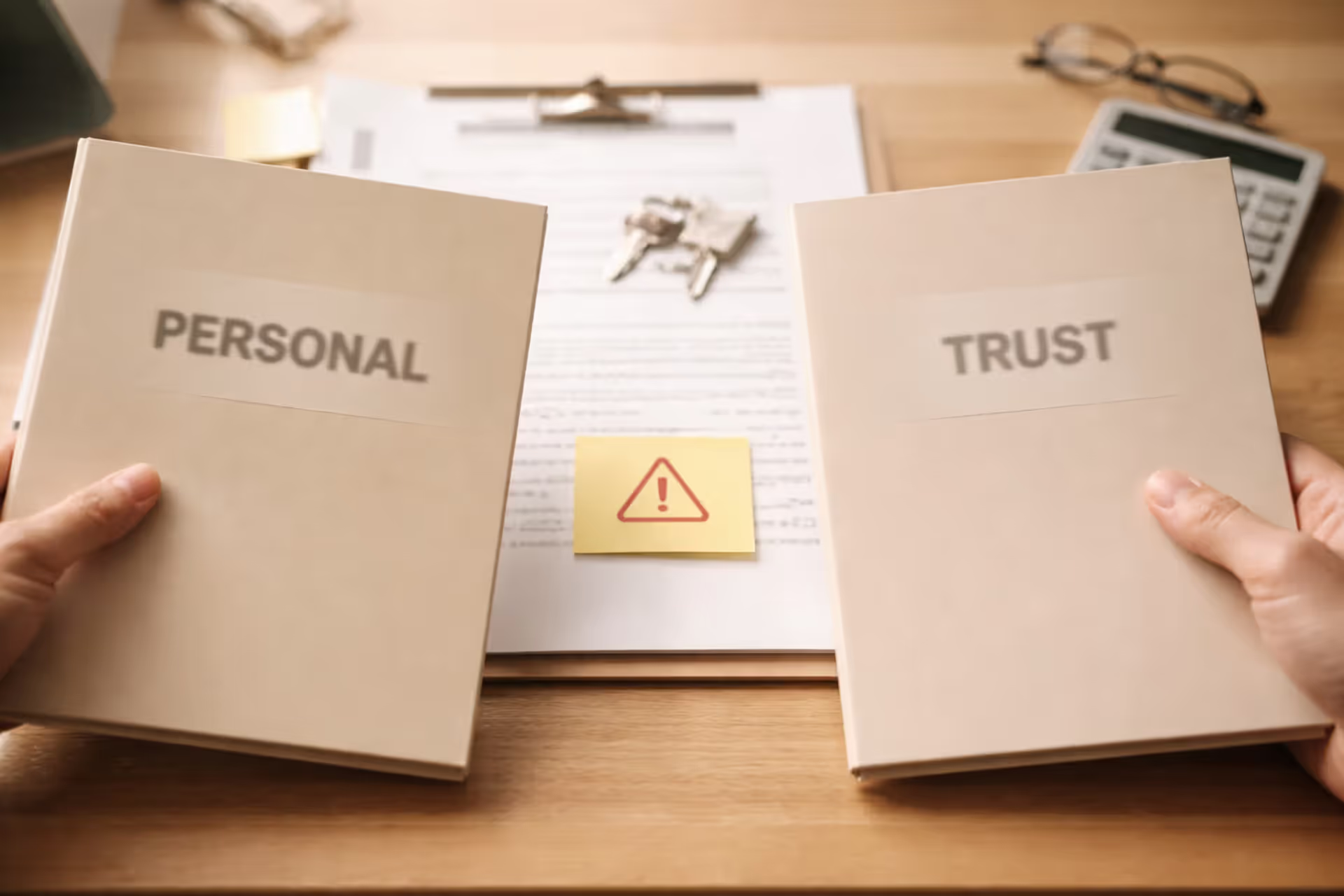

| Remedy Type | Purpose | When Used | Example Scenario |

| Expectation Damages | Compensates for the value plaintiff would have received from full performance | Standard remedy when financial losses can be proven with reasonable certainty | Land seller backs out; buyer recovers the $50,000 difference between $300,000 contract price and $350,000 market value |

| Reliance Damages | Reimburses expenses plaintiff incurred because they trusted the contract would be performed | Applied when expected profits are too uncertain to prove or when contract would have lost money | Event coordinator recovers $8,000 deposit and $3,000 in preparation expenses after entertainment vendor cancels |

| Restitution | Returns the value plaintiff already gave to defendant to prevent unfair enrichment | Used when contract is invalid, unenforceable, or plaintiff chooses to unwind the transaction | Homeowner recovers $25,000 deposit after construction company dissolves before starting any work |

| Specific Performance | Court orders defendant to actually fulfill their contractual obligations | Available when monetary damages won't adequately compensate and subject matter is genuinely unique | Buyer of authenticated Picasso painting compels seller to complete transfer rather than accepting cash payment |

When Courts Order Specific Performance Instead of Money

Specific performance law recognizes that some contracts involve such unique subject matter that monetary compensation falls short. Instead of awarding damages, courts order the breaching party to actually do what they promised. This equitable remedy comes with strict requirements and stays exceptional rather than routine.

The threshold question: is the subject matter truly unique? Courts have historically presumed all real estate qualifies because no two properties occupy identical locations. Even a cookie-cutter suburban home meets this standard. When a seller refuses to close on a house sale, the buyer can usually obtain specific performance forcing the property transfer.

Outside real estate, specific performance applies to genuinely one-of-a-kind items: original paintings by recognized artists, rare collectibles with provable authenticity, custom-manufactured equipment with no market substitutes, or businesses with distinctive characteristics. A contract to sell 1,000 bushels of commodity-grade wheat? You can buy that anywhere—specific performance won't apply. A contract to sell a Triple Crown-winning racehorse? That might qualify.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Real Estate Contracts and Unique Goods

Real estate transactions dominate the specific performance docket. Buyers who've found their ideal property can force reluctant sellers to complete the sale. The remedy works bidirectionally—sellers can force buyers to close and pay, though they more often pursue damages since most prefer cash over dealing with a hostile buyer.

Courts examine whether monetary damages would truly make you whole. A developer acquiring land for a specific zoning-dependent project might argue no other parcel serves their needs. A buyer seeking purely an investment property faces harder arguments since comparable properties exist. The more you demonstrate unique features—irreplaceable location near your business, proximity to elderly parents, special historical designation, specific zoning allowing your intended use—the stronger your specific performance claim becomes.

Personal property demands even stronger uniqueness showings. Mass-produced items never qualify. A vintage automobile might, depending on rarity and provenance. Business assets can qualify when they're integral to ongoing operations and replacement would cause substantial disruption. A manufacturer might obtain specific performance for specialized equipment if no substitutes exist and building replacement equipment requires years.

Why Specific Performance Is Rarely Granted

Courts hesitate to order specific performance for compelling reasons. The remedy demands ongoing judicial supervision ensuring compliance, burdening limited court resources. Judges can't effectively oversee complex performance obligations or monitor service contracts requiring sustained cooperation.

Personal service contracts almost never result in specific performance. Courts won't force employees to work for specific employers or compel entertainers to perform. Such orders raise Thirteenth Amendment concerns about involuntary servitude. Instead, courts might issue negative injunctions preventing defendants from working for competitors during the contract period.

The adequacy of legal remedies matters significantly. When money damages would fully compensate you, courts stick with monetary awards. Specific performance exists for situations where no amount of money solves the problem. A buyer seeking a suburban house virtually identical to thousands of others will likely receive damages equal to the difference between contract price and the cost of buying a comparable home elsewhere.

Undue hardship on defendants can defeat specific performance even when otherwise appropriate. Enforcing the contract would bankrupt the defendant or require them to violate other legal obligations? Courts may refuse the remedy. Balancing equities matters—when plaintiff's harm is modest but forcing performance would devastate the defendant, damages may be the only option.

Restitution: Recovering What You Already Gave

Restitution legal meaning centers on preventing unjust enrichment rather than enforcing contractual expectations. When you've conferred benefits on someone who then breached the contract, restitution allows recovery of what you gave. This remedy essentially reverses the transaction.

The classic scenario involves deposits or down payments. You pay $20,000 as a boat deposit, and the seller refuses delivery. Restitution returns your $20,000. You're not trying to get the boat or the benefit of your bargain—you simply want your money back because the seller shouldn't keep it without performing.

Restitution also works when contracts are void or voidable. When a contract fails for lack of consideration, impossibility, or illegality, neither party can enforce it through expectation damages. But if one party already performed, they can seek restitution preventing the other side from benefiting unfairly. A contractor completing half a project before discovering the contract violates local licensing laws can still recover reasonable value for work performed.

Restitution measures the value the defendant received, not necessarily what you spent. You provided services worth $15,000 market value but they only cost you $10,000 to deliver? Restitution gives you $15,000. Conversely, you spent $20,000 on preparations only benefiting the defendant by $12,000? You recover $12,000. Courts examine what the defendant gained, not your expenditures.

Quantum meruit—Latin for "as much as deserved"—allows recovery for services performed under implied contracts or when express contracts fail. A consultant working for months based on a handshake agreement can recover reasonable value for their services even without written documentation. The theory holds that defendants accepting benefits while knowing compensation was expected should pay for what they received.

Restitution becomes particularly valuable when expectation damages would be minimal but you've already conferred substantial benefits. You prepaid for services later turning out to be worth less than anticipated? Restitution recovers your payment without requiring proof the contract would have been profitable.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

How Courts Decide Which Remedy to Award

Judges don't rubber-stamp whatever remedy you request. They evaluate multiple factors determining what's appropriate given the circumstances. Your preference matters—plaintiffs typically elect their preferred remedy—but courts retain discretion adjusting awards based on equity and policy considerations.

The breach's nature influences the remedy. Material breaches going to the contract's heart justify full remedies. Minor breaches might yield nominal damages or no recovery. A two-day delay in a year-long construction project gets treated differently than complete abandonment.

Proof quality determines remedy availability. Can't prove expectation damages with reasonable certainty? Courts won't award them regardless of what you claim. Strong documentation—signed contracts, detailed invoices, email correspondence, audited financial records—supports higher awards. Vague testimony and speculation lead to reduced or denied claims.

Damages' adequacy matters for equitable remedies. Specific performance requires showing money won't make you whole. When damages would fully compensate you, that's what you'll receive. Courts prefer monetary awards because they're simpler to calculate and enforce.

Your post-breach conduct affects recovery. The mitigation duty requires reasonable efforts minimizing damages. You could have hired a replacement contractor for $15,000 but waited months and ultimately paid $25,000? Courts might limit recovery to $15,000. You can't let damages accumulate when reasonable alternatives exist.

Contract language shapes available remedies significantly. Well-drafted agreements specify remedies for different breach types, include liquidated damages provisions, or waive certain remedies. Courts generally enforce these provisions unless they're unconscionable. A clause stating "specific performance is the sole remedy for breach" limits your ability to seek damages.

Public policy sometimes restricts remedies. Courts won't enforce contracts for illegal activities or award damages violating public policy. Penalty clauses existing solely to punish rather than compensate are unenforceable regardless of contractual language.

Common Mistakes That Limit Your Available Remedies

Failing to mitigate damages ranks as the most devastating error. Once breach occurs, the law expects you to take reasonable steps minimizing losses. This doesn't mean accepting inferior alternatives or incurring substantial costs, but it does require acting sensibly. A landlord whose tenant breaks their lease must advertise the vacant unit and consider qualified applicants. A business losing a key supplier must seek replacement vendors at reasonable market prices.

Poor documentation undermines otherwise legitimate damage claims. Without records proving losses, even valid claims fail. Keep copies of all contracts, email correspondence, invoices, and financial statements. Document your mitigation efforts with dated notes and receipts. Claiming lost profits? Maintain detailed financial records showing business performance before and after the breach.

Missing statutes of limitations destroys perfectly valid claims. Every state sets deadlines for filing contract lawsuits—typically ranging from three to six years, though some states allow up to ten years for written contracts. Once that deadline passes, your claim dies regardless of its merit. The limitations period usually begins when the breach happens, though some states use when you discovered or reasonably should have discovered it.

Inadequate contract drafting limits remedy options significantly. Contracts should specify breach consequences: which remedies are available, whether liquidated damages apply, who pays attorney's fees, and how disputes get resolved. Generic form contracts often lack these provisions, leaving you arguing over what's appropriate after problems arise.

Waiving rights through conduct happens more than people realize. Continuing to accept partial performance or late payments without objection? Courts may find you waived strict compliance requirements. A pattern of accepting late deliveries makes claiming a single late delivery justifies termination much harder. Document your objections and explicitly reserve your rights.

Seeking incompatible remedies confuses your case. You can't simultaneously claim the contract should be enforced (specific performance) and that you want to undo it (restitution). Choose a coherent legal theory and stick with it. You can plead alternatives for procedural purposes, but your evidence and arguments should align with your chosen remedy.

Ignoring contractual dispute resolution provisions costs time and money. Many contracts mandate mediation or arbitration before litigation becomes available. Filing a lawsuit without completing these procedures may result in dismissal. Even when you're eager to reach court, you'll likely be forced to complete the contractual process first.

Frequently Asked Questions About Contract Remedies

Navigating contract remedies requires understanding both legal rights and practical realities. The remedy sounding best theoretically may not be achievable given your evidence, contract terms, or the defendant's financial situation. A $200,000 judgment for expectation damages means nothing when the breaching party has no collectible assets.

Before pursuing litigation, assess what you can realistically prove and what the defendant can actually pay. Consider whether the business relationship is worth preserving—sometimes negotiated settlements providing less than full legal remedies make more business sense than scorched-earth litigation destroying future opportunities. Document everything from day one, mitigate damages promptly, and consult with an attorney early to preserve your strongest remedy options.

Contract law provides multiple tools addressing breaches, but using them effectively requires preparation, solid evidence, and strategic thinking. Understanding differences between expectation damages, reliance damages, specific performance, and restitution helps you choose the right approach for your situation and strengthens your position whether negotiating a settlement or preparing for court.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on Legal Insights is provided for general informational purposes only. It is intended to offer insights, commentary, and analysis on legal topics and developments, and should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for professional consultation with a qualified attorney.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Laws and regulations may vary by jurisdiction and may change over time. The application of legal principles depends on specific facts and circumstances.

Legal Insights is not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content, or for any actions taken based on the information provided on this website. Users are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situation before making any legal decisions.