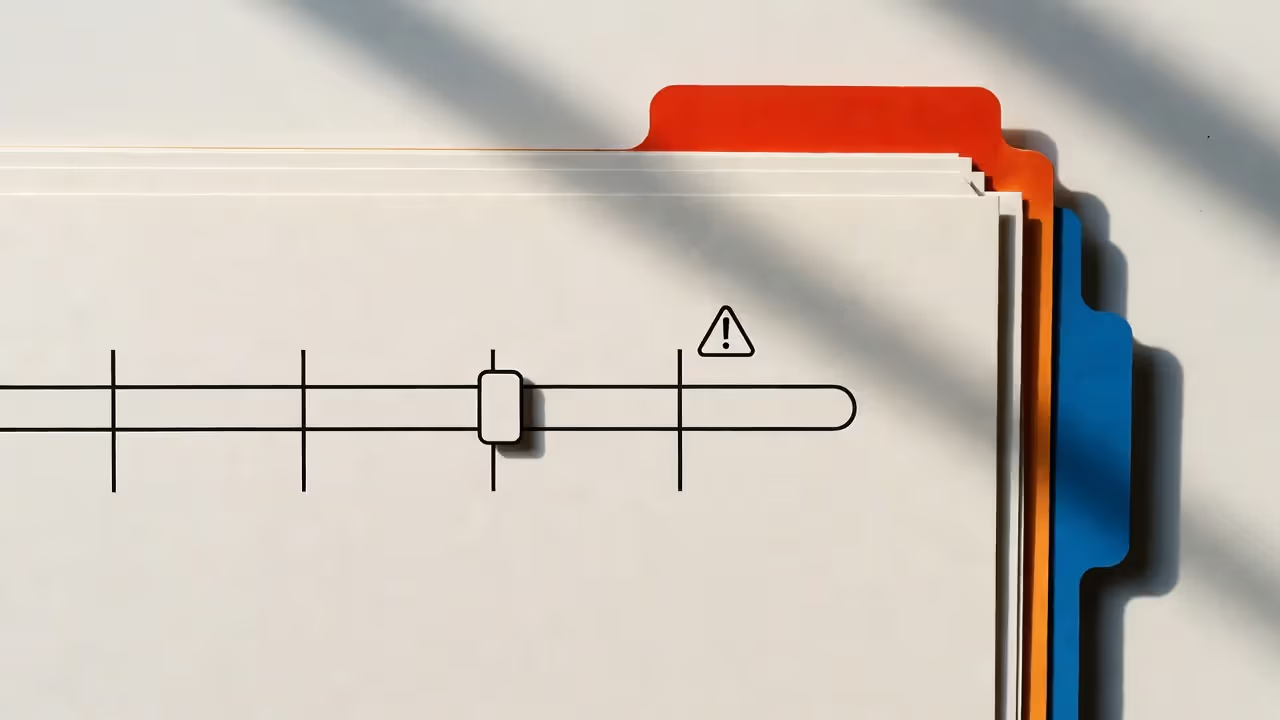

The line is awareness of risk.

Negligence vs Recklessness: Understanding the Legal Difference in Liability Cases

Two drivers cause accidents on the same day. The first one glances at their phone to check a notification—eyes off the road for maybe three seconds—and slams into a stopped vehicle. The second one drinks until they can barely stand, then decides to drive anyway, speeding through crowded streets. Both created crashes. Both hurt people. Yet the law treats these situations as fundamentally different animals.

Understanding where behavior falls on this legal spectrum determines everything: how much compensation you might collect, whether criminal charges get filed, even if insurance pays anything at all. The dividing line? What was running through someone's mind right before disaster struck.

That's the part that trips people up. These categories blur together in ways that can make or break a case.

What Constitutes Negligence Under US Law

Personal injury cases in America typically revolve around negligence claims. Winning requires establishing four distinct elements—miss just one piece, and your entire case collapses.

Duty comes first. Someone owed you a legal obligation to exercise care. Drivers must follow traffic laws and avoid crashing into others. Store owners can't leave spills unattended without warnings. Surgeons need to apply the same techniques their competent peers would use in similar situations.

Breach is where the "reasonable person" standard shows up. Courts imagine this hypothetical individual with average judgment and common sense, then ask: would this person have acted this way? It's not about what the defendant personally believed was careful—the test is objective. A contractor who installs a deck railing that collapses under normal use breached their duty, regardless of whether they thought their work seemed sturdy.

Causation connects the dots. The careless act must directly lead to the injury. There's also a foreseeability component here—was this the type of harm you'd reasonably expect from that kind of mistake? When someone runs a red light and T-bones your car, causation is straightforward. But they're not responsible if some completely unrelated accident happens three miles away an hour later.

Damages mean actual harm occurred. Medical bills, broken bones, destroyed property, lost paychecks, ongoing physical pain—these qualify. But if someone acts carelessly and by pure luck nobody gets hurt? There's nothing to recover for. No harm, no case.

Here's a concrete scenario. A grocery chain mops floors at 3 PM on a Saturday—peak shopping time. Nobody bothers with those yellow warning cones. An elderly customer walks through, hits the wet tile, falls hard, and breaks her hip. The store owed shoppers a responsibility to maintain safe conditions or warn about hazards. Skipping the warning signs violated that duty. The slippery floor directly caused her fall and fracture. She's facing hip replacement surgery and six months of rehab. All four elements line up—that's what negligence legal definition looks like in practice.

Medical malpractice follows this identical framework but with specialized professional standards. A surgeon who leaves a surgical clamp inside a patient's body during a routine procedure? That violates every duty healthcare providers owe patients. When the forgotten instrument triggers a serious infection requiring emergency surgery to remove it, you've got clear causation and damages.

Car accidents supply endless negligence examples. You're fiddling with your GPS settings, not watching the road ahead, and don't notice traffic has completely stopped. You rear-end the vehicle in front. That's a breach—you failed to maintain proper attention and safe following distance. The collision causes neck injuries and vehicle damage. Textbook negligence: you missed a risk you should've spotted.

Something critical about the reasonable person standard—it ignores your individual characteristics. Brand new to driving? Been doing it for forty years? Doesn't matter one bit. Everyone faces the same baseline expectation. The law demands that minimum level of care from everyone, period.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

How Recklessness Differs from Ordinary Negligence

This is where behavior jumps to a whole different level. The recklessness meaning law applies when someone actually spots the danger ahead and decides, "Eh, I'll take my chances." With negligence, you overlook something you should've noticed. With recklessness, you see it clearly—and barrel forward anyway.

That mental shift changes everything. A negligent person makes a mistake or fails to notice a hazard. A reckless person recognizes the serious danger but consciously chooses to create that risk. They're not trying to hurt anyone (which would be intentional harm). They just don't care enough about the risk to stop.

These tort mental state differences show up clearest in driving scenarios. Daydreaming and drifting across lane markers without checking mirrors? Negligence—failed attention. But throwing back six shots of tequila, fully aware you're drunk, then getting behind the wheel? Reckless. You know alcohol destroys judgment and reaction time, yet you deliberately create that hazard anyway.

Extreme speeding often crosses this line. Going 48 in a 40 zone? Probably just careless. Doing 95 through a neighborhood full of kids playing? That demonstrates reckless disregard. At that speed, there's zero chance of stopping if someone steps into the road, and you know it—but you maintain that speed regardless.

Here's a construction site example. Scaffolding shows visible damage—cracked support beams, missing safety rails, the whole structure looks ready to collapse. Multiple workers report concerns to their supervisor. The supervisor tells everyone to keep using it because the project's behind schedule. That's recklessness in action. Management spotted the substantial collapse risk but prioritized deadlines over safety.

Proving someone actually knew about the risk—not just should've known—makes recklessness claims significantly harder than negligence. You need evidence showing the defendant understood the danger. Text messages help enormously. So do emails, witness statements about specific conversations, or patterns showing repeated dangerous choices despite warnings.

Recklessness sits between negligence and intentional harm on the fault scale. The reckless person doesn't want injuries to occur—that's what distinguishes it from intentional torts like assault. But consciously deciding to create serious dangers makes the behavior far more blameworthy than simple carelessness.

The Spectrum of Fault: Where Each Standard Falls

Think of liability standards less as separate boxes and more as points along a continuum. Courts created several intermediate levels because behavior doesn't always fit neatly into rigid categories.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Gross Negligence as the Middle Ground

Gross negligence bridges the gap between ordinary carelessness and recklessness. It means conduct so absurdly below reasonable standards—so ridiculously inadequate—that it suggests complete indifference to consequences, even without proving the person consciously thought about the specific danger.

Consider a nursing home that leaves bedridden, nonverbal residents without water for fourteen consecutive hours during a heat wave. Staff might not have literally thought "these people could die and I don't care," but the failure is so extreme it goes way beyond simple negligence. The departure from basic care standards is both obvious and severe.

Several states treat gross negligence essentially identical to recklessness when determining whether punitive damages apply. Others maintain distinctions, requiring actual conscious awareness for recklessness but still permitting punitive awards for gross negligence under certain circumstances.

Willful and Wanton Conduct

Certain jurisdictions use "willful and wanton" terminology, which generally means the same thing as recklessness or occupies that same territory. The precise language varies by location, but the core concept remains consistent: behavior demonstrating extreme indifference to whether others get hurt.

| Standard of Conduct | Mental State Required | Awareness of Risk | Typical Damages Available | Primary Legal Context |

| Negligence | No intent to cause harm; simply didn't exercise reasonable caution | Failed to perceive the danger (though should have noticed) | Compensatory damages only: medical expenses, lost income, pain/suffering | Civil injury lawsuits |

| Gross Negligence | Conduct dramatically below acceptable standards; suggests extreme indifference | Risk might or might not have been consciously perceived, but was clearly obvious | Compensatory damages; certain jurisdictions permit punitive damages | Civil claims; sometimes determines insurance coverage |

| Recklessness | Recognized the substantial danger; proceeded despite that knowledge | Actually understood the risk and continued regardless | Compensatory plus punitive damages typically allowed | Both criminal and civil cases; frequently triggers insurance policy exclusions |

| Intentional Conduct | Specifically desired to cause that particular harm | Fully aware and deliberately intended the result | Compensatory and punitive damages; potentially enhanced criminal sentences | Criminal prosecution; civil intentional tort lawsuits; insurance virtually never pays |

Where behavior lands on this spectrum matters enormously because each step upward increases potential liability and transforms available remedies. These fault levels explained depend heavily on proving mental state, which requires different evidence types.

How Courts Determine Which Standard Applies

Author: Courts infer mental state from evidence.;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Judges and juries don't just accept a plaintiff's declaration that someone acted recklessly rather than negligently. They analyze specific factors to figure out the appropriate classification.

The severity of the risk created matters significantly. Creating a tiny chance of minor harm typically remains in negligence territory. Creating a strong likelihood of serious injury or death points toward recklessness—particularly when the defendant understood how severe potential harm could be. A contractor who skips one safety inspection during a small residential job might be negligent. That same contractor ignoring every single safety protocol while building a forty-story highrise? That demonstrates conscious disregard for catastrophic risks.

Evidence showing what the defendant actually knew becomes essential. Did warnings reach them? Were there earlier incidents? Did they receive training or possess specialized knowledge making them aware of these dangers? A homeowner who genuinely doesn't realize their deck boards have rotted through might just be careless. A licensed contractor who examines that rot, recognizes the structure is unsafe, but tells the homeowner everything's fine? That crosses into reckless territory.

Behavior before and after the incident provides clues. Someone who immediately acknowledges their error and tries to help probably wasn't reckless. Someone who flees the scene, destroys evidence, or continues the dangerous conduct afterward? That pattern suggests they consciously knew something was seriously wrong all along.

Time matters too. Instantaneous decisions made under pressure rarely qualify as reckless. Dangerous conduct continuing across days, weeks, or months, with multiple opportunities to recognize the problem and stop? That more clearly shows conscious disregard.

State-specific definitions vary considerably. Some require showing harm was "virtually certain" to happen. Others apply lower thresholds like "high probability" or "substantial risk." A handful of states don't even recognize recklessness as a distinct category in certain contexts, jumping directly from negligence to intentional misconduct.

The burden of proof remains "preponderance of evidence" for civil cases—meaning more likely true than not. However, establishing recklessness demands stronger evidence than proving negligence because you're establishing someone's internal thought process. Circumstantial evidence usually does the heavy lifting here. Defendants rarely announce "I recognized this was dangerous and did it anyway," so you've got to construct your case from surrounding circumstances.

Expert witnesses frequently help establish standards. In medical contexts, an expert might testify the defendant's conduct deviated so dramatically from accepted practice it demonstrates conscious disregard for patient safety. In product liability scenarios, experts might demonstrate a manufacturer knew about safety defects based on internal testing data they possessed.

Pattern evidence carries enormous weight. A trucking company that routinely violates federal rest requirements demonstrates reckless disregard for driver fatigue dangers. One violation might be careless. Systematic violations with documented knowledge of fatigue-related crash risks? That suggests recklessness.

The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.

— Oliver Wendell Holmes

Why the Distinction Matters for Your Case

Whether conduct gets labeled negligent versus reckless creates practical consequences that dramatically reshape case outcomes and financial recovery.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Compensatory damages—the money covering medical bills, lost paychecks, property repairs, and physical pain—get awarded regardless of whether you're proving negligence or recklessness. The calculation doesn't change based on fault level. A shattered pelvis costs the same to treat whether negligence or recklessness caused it.

Punitive damages transform everything. Most jurisdictions won't permit punitive damages for ordinary negligence. These damages exist specifically to punish exceptionally bad conduct and discourage others from similar choices. Recklessness usually clears the threshold for punitives, potentially adding hundreds of thousands or millions to a jury's award.

Say you've accumulated $150,000 in medical expenses and lost earnings from someone's negligent actions. You'd collect compensatory damages for that amount. But when reckless conduct caused those identical injuries, you might receive that $150,000 in compensatory damages plus another $600,000 in punitives if the jury decides the defendant's conscious disregard deserves punishment.

Insurance coverage creates enormous practical differences. Most liability policies cover negligent acts—that's their fundamental purpose. Many policies specifically exclude reckless, willful, or wanton conduct though. An insurer might deny the entire claim once they establish the insured acted recklessly.

This creates interesting strategic dynamics. Defendants want conduct characterized as negligence so insurance covers everything. Plaintiffs want recklessness for access to punitives. But here's the twist: if the defendant lacks personal assets, you might actually prefer negligence classification that keeps insurance money available rather than a recklessness classification triggering a policy exclusion that leaves you holding an uncollectible judgment.

Criminal prosecution enters the picture with reckless behavior. Negligence alone rarely supports criminal charges outside specialized statutes like vehicular manslaughter laws. Reckless conduct more frequently crosses into criminal territory. Offenses like reckless endangerment, reckless driving, and similar charges require proving conscious disregard for risk.

A civil plaintiff and criminal prosecutor can pursue cases at the same time. The civil plaintiff only needs preponderance of evidence (more likely than not—basically 51% certainty). The prosecution needs proof beyond reasonable doubt (maybe 95% certainty or higher). Someone might lose the civil case but win the criminal defense because of those different proof thresholds.

Statutes of limitations occasionally vary by fault level. Most injury claims face identical filing deadlines whether negligence or recklessness is involved, though a few states provide extended periods for reckless conduct or apply discovery rule exceptions more liberally when recklessness gets alleged.

Settlement negotiations shift dramatically when recklessness is credibly threatened. Defendants face potential punitive exposure and possible criminal charges, creating tremendous pressure to settle. But if insurance won't cover a recklessness finding, they might fight ferociously to keep the conduct classified as negligence instead.

Common Mistakes When Arguing Negligence vs Recklessness Claims

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Attorneys and self-represented litigants make predictable errors navigating these fault levels, and these mistakes destroy cases.

Confusing the standards happens constantly. People call conduct "reckless" because it caused catastrophic harm or seems really, really awful. But devastating injuries don't automatically equal recklessness. How bad the outcome was doesn't determine fault level—what matters is the defendant's mental state beforehand. A momentary distraction causing life-altering injuries remains negligence when the person didn't consciously recognize the risk being created.

The reverse problem happens too. Plaintiffs undercharge claims, framing obvious conscious disregard as simple negligence. That leaves punitive damages sitting uncollected on the table. Once you've framed a case as negligence in pleadings, pivoting to recklessness later becomes extraordinarily difficult.

Inadequate evidence about mental state kills countless recklessness claims. Plaintiffs allege reckless conduct but present zero evidence proving the defendant actually knew about the risk. Arguing "they should've known" establishes negligence, nothing more. Winning on recklessness demands proof of actual awareness—emails acknowledging dangers, testimony about specific warnings received, documentation of prior similar incidents the defendant knew about, or circumstances making awareness essentially certain.

Say you're alleging a property owner recklessly maintained a dangerous condition. Proving the condition existed isn't enough. You need evidence the owner knew—maintenance requests they got, prior injury complaints, inspection reports they reviewed, or a condition so glaring and longstanding that knowledge gets reasonably inferred.

Misunderstanding your jurisdiction's specific definitions creates problems since terminology and thresholds differ significantly between states. Some require proving the defendant knew harm was "virtually certain" to result. Others use "high probability" language. Several require showing the defendant literally didn't care whether harm occurred. You need to research your state's precise standard before building case strategy.

State law also determines whether gross negligence suffices for punitive damages or whether you must prove true recklessness. Filing in a jurisdiction requiring recklessness when you can only establish gross negligence means punitives are unavailable.

Ignoring gross negligence as a strategic alternative sometimes makes tactical sense. When proving conscious awareness looks challenging but the conduct was extraordinarily careless, gross negligence might prove easier to establish while still potentially accessing enhanced damages in certain jurisdictions. It serves as a middle path when recklessness feels like an overreach but ordinary negligence undervalues what occurred.

Forgetting about insurance implications leads to hollow victories. Winning a massive verdict including punitive damages accomplishes nothing if the defendant's broke and their insurance policy excludes reckless behavior. Sometimes accepting negligence classification with guaranteed insurance money produces better actual recovery than pursuing recklessness that triggers an exclusion leaving you with an uncollectible judgment against someone lacking assets.

Failing to preserve evidence of mental state quickly proves costly. Text messages, emails, and internal company documents showing risk awareness get deleted constantly. Security footage gets recorded over. Witnesses' memories fade or they become unavailable. Quick investigation and evidence preservation matter even more in recklessness cases because proving someone's thoughts requires more sophisticated evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions About Negligence and Recklessness

Grasping the distinction between negligence and recklessness affects every phase of an injury case, from initial evaluation through trial or settlement negotiations. Negligence cases center on whether someone used reasonable care and whether their failure caused harm. Recklessness cases add that crucial layer of proving the person consciously recognized substantial risks and proceeded regardless.

This classification shapes case value, available damages, insurance coverage, and overall litigation strategy. A correctly identified recklessness case unlocks punitive damages that can multiply recovery many times over. But claiming recklessness without adequate mental state evidence can backfire, damaging your entire claim's credibility.

The fault spectrum exists because people's behavior varies in how blameworthy it actually is. Someone making an honest mistake deserves different treatment than someone knowingly creating serious dangers. Courts developed these distinct standards to match liability with culpability—ensuring the most careless actors face the greatest consequences.

Whether you're evaluating a potential claim, defending against allegations, or trying to understand a legal situation you're navigating, focus on that mental state question. What did the person know, when did they know it, and did they recognize the risks their conduct created? Answering those questions determines where behavior lands on the fault spectrum and what legal consequences follow.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on Legal Insights is provided for general informational purposes only. It is intended to offer insights, commentary, and analysis on legal topics and developments, and should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for professional consultation with a qualified attorney.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Laws and regulations may vary by jurisdiction and may change over time. The application of legal principles depends on specific facts and circumstances.

Legal Insights is not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content, or for any actions taken based on the information provided on this website. Users are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situation before making any legal decisions.