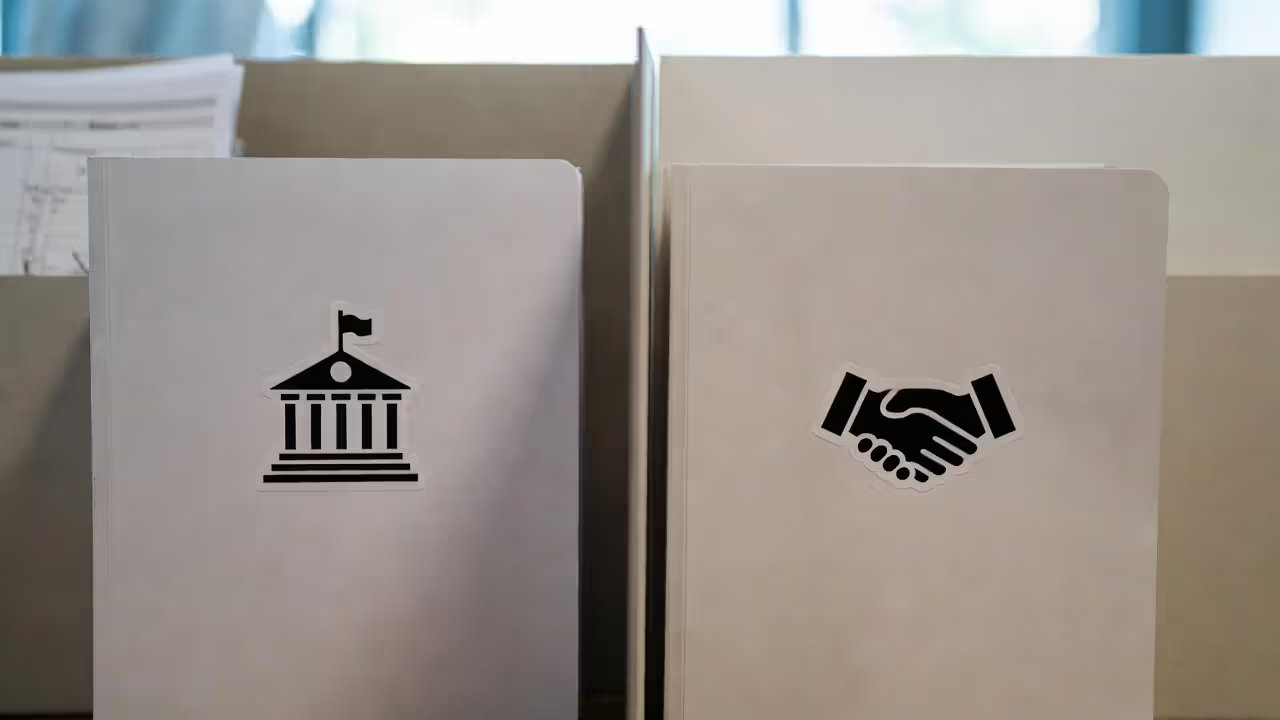

Two legal tracks: government vs private disputes.

Public vs Private Law: Understanding the Two Main Branches of the US Legal System

Here's something most Americans don't realize: the legal system operates on two completely different tracks. One track handles your fights with neighbors, business partners, or that contractor who botched your kitchen renovation. The other track kicks in when government—whether federal, state, or local—gets involved.

Public law covers everything involving government authority and power. Think criminal charges, regulatory agencies shutting down restaurants, or challenges to unconstitutional statutes. Private law? That's you versus another person or company—contract disputes, car accidents, divorce proceedings. Knowing which track your legal problem runs on changes everything: the attorney you'll hire, the court you'll end up in, even whether you can drop the case if you change your mind.

What Defines Public Law and Private Law?

Public law creates the rulebook for how government operates and interacts with everyone under its jurisdiction. Every time a government body flexes its muscle—prosecuting crimes, enforcing environmental regulations, interpreting the Constitution—public law sets the boundaries. The crucial element? Government appears as a party representing everyone's shared interests, not just one person's complaint.

Here's a concrete example. When someone breaks into your house, the break-in violates your personal security. But the district attorney who prosecutes that burglary isn't working for you specifically. They're representing society's collective interest in deterring theft and maintaining order. You'll testify as a witness, but you can't hire the prosecutor or fire them if you disagree with their strategy.

Now flip to private law. These are fights between non-governmental parties—you and your landlord arguing about who pays for the broken furnace, two businesses battling over a supply contract, siblings contesting mom's will. Someone claims another person or entity owes them something or caused them harm. Courts referee these disputes, but they don't take sides. Both parties stand on equal ground.

The dividing line? Ask yourself who got hurt and in what way. Public law protects interests we all share collectively. Assault doesn't just harm the victim—it threatens everyone's safety and society's peace. That's why prosecutors can move forward even if victims want to drop charges. Private law protects your individual stake in things: your property, your agreements, your freedom from someone else's carelessness.

This classification drives real consequences. Break a public law and you're looking at jail time, fines paid to the government, criminal records that follow you forever. Lose a private lawsuit? You'll probably write a check to the other side or get a court order telling you to do (or stop doing) something. No matter how badly you breached that contract, the other party can't send you to prison.

Categories and Examples Within Public Law

Constitutional Law and Government Structure

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Constitutional law sits at the top of the hierarchy, creating the blueprint for government itself while protecting citizens from government overreach. The U.S. Constitution and all fifty state constitutions spell out what government can and cannot do. They divide power between branches, allocate authority between federal and state levels, and draw red lines government cannot cross.

Say your city council passes an ordinance banning political signs in residential yards. Constitutional law determines whether that restriction tramples your First Amendment rights. When Congress authorized the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate, constitutional law analyzed whether the Commerce Clause permitted that federal intrusion. These aren't just academic exercises—the answers affect millions of people simultaneously.

Watch how constitutional challenges ripple outward. A high school student in Alaska unfurls a "BONG HiTS 4 JESUS" banner across the street from school during a parade. School officials suspend him. He sues claiming First Amendment violation. Whatever the Supreme Court decides doesn't just resolve that student's suspension—it sets precedent for how all public schools nationwide can regulate student speech. One case, universal impact. That's constitutional law functioning as public law.

Administrative Law and Public Authority Regulations

The federal government operates roughly 430 agencies. States add hundreds more. These agencies—EPA, FDA, FCC, OSHA, state medical boards, local zoning commissions—wield delegated government power over specific domains. Administrative law governs how these agencies make rules, enforce them, and punish violations.

Take a restaurant owner facing a health department shutdown after one critical inspection. She's navigating administrative law territory. The health inspector exercised government authority (police power to protect public health). The owner can't just sue in regular court like she would if a supplier breached a contract. She must follow the agency's appeal procedures first, exhaust administrative remedies, then potentially seek judicial review arguing the agency exceeded its authority or violated due process.

Or consider this scenario: The Department of Labor announces new overtime eligibility rules affecting millions of workers. Business groups immediately challenge the rule. That litigation exemplifies public authority law—unelected agency officials are exercising government power that affects entire industries. The rules don't apply just to the parties who sue. Once finalized, they bind everyone in the regulated category.

Criminal Law as a Public Interest Matter

Criminal law crystallizes the public law concept better than any other category. Crimes harm society, not just individual victims, so the state prosecutes in everyone's name. Notice the case styling: "People v. Hernandez" or "State of Texas v. Johnson." The victim's name doesn't appear as a party.

This structure creates situations that confuse non-lawyers. A domestic violence victim wants charges dropped—they've reconciled, gone to counseling, and the relationship is healthy now. Tough luck. The prosecutor often proceeds anyway because society's interest in stopping domestic violence exists independently of this victim's wishes. Prosecutors answer to the public, not victims.

Criminal law also demonstrates government's unique coercive power. Convicted defendants lose liberty through imprisonment. They endure supervised probation restricting their movements. They carry permanent records affecting employment, housing, voting rights, gun ownership. These harsh consequences—unthinkable in private disputes—reflect the collective judgment that certain conduct deserves punishment beyond compensating victims.

Categories and Examples Within Private Law

Contract Law Between Private Parties

Contract law supplies the enforcement mechanism for voluntary agreements. When you book a venue for your wedding, lease office space, hire a freelancer, or buy concert tickets, contract law fills in gaps the parties didn't address and provides remedies when someone doesn't deliver.

Picture this: A software startup contracts with a marketing agency for a six-month campaign costing $50,000. Four months in, the startup fires the agency claiming poor performance. The agency sues for the remaining balance. That's private dispute territory—two businesses fighting over their agreement. No government interest exists in who wins. The court will interpret the contract terms, determine whether either party breached, assess damages, and issue a judgment. If the parties settle mid-litigation, the judge closes the file without blinking.

Contract law respects party autonomy extensively. Businesses can choose which state's law governs (within reason), require arbitration instead of litigation, cap damages, and structure countless other terms. Government provides the enforcement machinery but largely stays out of the substance. You can make a terrible deal—courts won't rescue you from bad business judgment.

Tort Law and Personal Injury Disputes

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Tort law addresses civil wrongs causing injury. Someone's wrongful conduct—whether intentional, negligent, or in some cases regardless of fault—harmed you. You sue seeking compensation for your specific losses.

Consider a distracted driver who runs a stop sign, T-bones your car, and sends you to the hospital with a broken leg and concussion. You file a personal injury lawsuit. This exemplifies private law dispute mechanics. You're not asking the court to punish the driver for society's benefit (though criminal charges might come separately). You want payment for medical bills, lost wages, damaged property, and pain and suffering—compensation for individualized harm.

Tort cases span broad territory: medical malpractice, slip-and-falls on business premises, defective products, defamation, fraud, trespass. Some involve intentional wrongdoing, others mere carelessness. But all share the characteristic that private parties seek monetary redress for particularized injuries, not punishment or societal protection.

Property and Family Law Matters

Property disputes arise when people disagree about who owns something or what rights they hold in it. Your neighbor's fence crosses three feet onto your land—you sue to establish the boundary and remove the encroachment. Your landlord won't return your security deposit—you file in small claims court. A competitor uses a confusingly similar trademark—you sue for infringement. These conflicts pit private parties against each other over property interests.

Family law covers marriage, divorce, child custody, adoption, and inheritance. Most of these are intensely private matters. A couple divorcing after twenty years must divide accumulated property, determine spousal support, and if they have kids, establish custody and child support. They're dissolving their private relationship and unwinding their financial entanglement. Courts provide structure and enforce minimum standards (especially protecting children), but this isn't government pursuing societal interests.

One wrinkle: child protective services removing kids from dangerous homes mixes public and private law. The state exercises government authority (parens patriae power to protect vulnerable children)—definitely public law. But parents fighting reunification are asserting private family bonds. Family law sometimes straddles both worlds, though most cases remain purely private.

The law is reason, free from passion.

— Aristotle

How Public and Private Law Differ in US Court Proceedings

Procedural differences between these two branches affect everything from who can sue to what you might win.

| Feature | Public Law Cases | Private Law Cases |

| Who's Involved | Government agency, prosecutor, or official versus individual or organization; state represents everyone's interests | Two or more non-governmental parties—could be individuals, businesses, or organizations; no government party exercising sovereign authority |

| Who Files | Government officials (prosecutors, agency attorneys) decide whether to bring charges or enforcement actions; private citizens need standing showing concrete injury to challenge government action | The injured private party controls whether to sue and can voluntarily dismiss or settle on any terms |

| What's the Goal | Protecting society's shared interests, maintaining public order, ensuring government stays within constitutional bounds, punishing wrongdoers, deterring future violations | Making the injured party whole through compensation, enforcing agreements between parties, resolving private disputes, restoring injured parties to their prior position |

| Available Outcomes | Prison time, fines paid into government coffers, probation with supervision, criminal record, orders stopping government from violating rights, declarations about what the law means | Money damages paid from defendant to plaintiff, court orders requiring specific actions or prohibiting conduct, contract enforcement, property division |

| Proof Required | Beyond reasonable doubt in criminal cases (very high standard); preponderance of evidence or clear and convincing evidence in administrative proceedings and constitutional challenges | Preponderance of the evidence (more likely than not—just over 50%) in most civil cases; higher standards for fraud or punitive damages |

| Case Examples | U.S. v. Martinez (drug trafficking prosecution), Sierra Club v. EPA (challenging agency regulation), NAACP v. Governor (constitutional challenge to voting law) | Garcia v. Prestige Homes LLC (construction defect), Chen v. Park (car accident), In re Marriage of Thompson (divorce), Acme Corp. v. Beta Industries (breach of contract) |

| Where Cases Go | Criminal divisions of state and federal courts, specialized administrative law courts, federal court for constitutional challenges, agency tribunals with appeals to regular courts | Civil divisions, small claims courts for smaller amounts, family court, probate court, optional private arbitration or mediation |

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Standing requirements show the starkest contrast. Want to challenge a government action in court? You must demonstrate direct, particularized injury—not just generalized grievance. Taxpayers generally can't sue over government spending they dislike unless they show concrete harm beyond sharing the tax burden. But in private cases, anyone directly injured by another's breach or wrongful act automatically has standing.

Control over the litigation differs dramatically too. Criminal defendants can't force prosecutors to drop charges or accept plea deals—prosecutors hold unilateral dismissal power and exercise broad discretion. In private lawsuits, plaintiffs run the show. They decide whether to file, can settle over the defendant's objection, and can voluntarily dismiss their complaint. This reflects contrasting philosophies: public law pursues societal interests transcending individual preference; private law respects individual autonomy.

Common Misconceptions: When Public and Private Law Overlap

Many real-world situations trigger both frameworks simultaneously, causing confusion about which rules control.

A drunk driver kills someone in a crash. The district attorney files vehicular homicide charges—that's public law punishing conduct threatening everyone's safety. The victim's spouse files a wrongful death lawsuit—that's private law seeking compensation for the family's loss. Identical facts, two separate cases running on parallel tracks with different parties, standards, and potential outcomes. The driver might beat the criminal charge (prosecutor couldn't prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt) yet still lose the civil case (spouse proved liability by a preponderance). Or vice versa.

Sometimes government acts as a private party rather than exercising sovereign authority. A city purchasing land for a park negotiates price like any buyer would. If disputes arise over contract terms, that's a private matter despite government involvement. Similarly, when an off-duty postal worker causes a fender-bender, the resulting lawsuit follows private law even though the defendant works for government. The postal worker wasn't exercising government authority—just driving carelessly like anyone else might.

Constitutional principles occasionally surface in private litigation. An employer fires a salesperson who signs a non-compete agreement. The salesperson sues claiming breach of contract. The employer defends citing the non-compete. The salesperson argues the agreement violates public policy protecting speech and economic freedom—constitutional values even though it's a private dispute. Courts must balance freedom of contract (private law) against constitutional principles (public law) when evaluating the non-compete's enforceability.

Regulatory violations sometimes generate private lawsuits too. A factory violates Clean Air Act emission standards. EPA pursues enforcement—public law. Neighbors sickened by the pollution sue for damages—private law. The regulatory violation might establish negligence per se in the private case, but neighbors still must prove their individual injury and causation. They can't simply enforce the regulation the way EPA would.

These overlaps demand careful analysis. A skilled attorney identifies which frameworks apply, what remedies each permits, and how different proceedings might interact strategically. Criminal convictions can create collateral estoppel in subsequent civil cases—defendants can't relitigate facts the criminal jury already found. But criminal acquittals don't prevent civil liability because standards differ.

Author: Michelle Granton;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Why This Classification Matters for Your Legal Rights

Getting the classification right determines which protections apply and what moves are available.

A state nursing board denies your license renewal after a complaint. You're dealing with public law—an agency exercised regulatory authority affecting your ability to practice your profession. You must navigate administrative appeal procedures, meet strict deadlines for judicial review, and ultimately prove the board acted arbitrarily, capriciously, or beyond its statutory authority. You can't just sue for breach of contract because no private agreement exists. You need an attorney experienced with that specific agency and administrative law generally.

Flip the scenario: your general contractor disappears with a $30,000 deposit, leaving your kitchen half-demolished. That's private law. You sue for breach of contract and fraud, seeking return of the deposit plus damages for completing the work properly. You control the timeline (within statutes of limitations), can settle if the contractor offers partial payment, and need a construction litigation attorney familiar with contract and consumer protection law. Unless the contractor's conduct also violated criminal fraud statutes—a separate public law matter with separate proceedings—no prosecutor will touch this.

Businesses need this classification for compliance and risk management. Violating an OSHA workplace safety regulation triggers government enforcement you cannot negotiate away—the agency pursues public interests. But breaching a supply contract is private. The other party might accept late delivery, partial shipment, or price adjustments. Wildly different strategies apply.

Evidence and defenses shift dramatically too. Criminal defendants enjoy robust constitutional protections: Fourth Amendment limits on searches, Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, Sixth Amendment right to counsel. These protections barely apply in private litigation. You can generally be compelled to testify against your financial interests (except narrow Fifth Amendment privilege). Evidence obtained through private searches—a spouse snooping through emails—is usually admissible even though the same search by police would violate the Fourth Amendment.

Insurance coverage often turns on this classification. Commercial general liability policies typically cover negligence claims (private law) but exclude intentional wrongdoing and criminal acts. Professional liability insurance covers malpractice lawsuits but not state licensing board sanctions. Knowing which framework applies helps predict whether coverage exists.

For individuals challenging government action, recognizing the public law nature shapes realistic expectations. Courts defer substantially to agency expertise within their regulatory domains. Constitutional claims require proving government action (purely private conduct doesn't trigger constitutional scrutiny) and often face qualified immunity—officials can't be held liable unless they violated "clearly established" law. Private disputes between equal parties avoid these hurdles.

Frequently Asked Questions About Public and Private Law

The distinction between public and private law isn't just academic classification—it's the organizational principle underlying the entire American legal system. Public law creates boundaries around government power while pursuing collective societal interests through constitutional interpretation, regulatory enforcement, and criminal prosecution. Private law facilitates dispute resolution between non-governmental parties, providing remedies when agreements fail or wrongful conduct causes individualized harm.

These categories determine procedural rules, available remedies, and litigation control. Criminal prosecution proceeds whether victims cooperate because public safety transcends individual preferences. Private lawsuits remain under plaintiff control since individual interests are at stake. Government agencies wield regulatory authority that can't be bargained away, while private parties structure contracts on mutually agreeable terms and settle lawsuits however they choose.

The classification carries practical significance for anyone navigating legal issues. Identifying whether your situation involves public or private law helps you find attorneys with appropriate expertise, understand realistic outcomes, and develop effective strategy. Many situations implicate both frameworks—single incidents triggering both criminal prosecution and civil liability require navigating parallel legal tracks with different rules.

America's public/private divide reflects core values: protecting collective interests while respecting individual autonomy, constraining government power while providing dispute resolution mechanisms, balancing societal needs against personal rights. Recognizing which category applies to your circumstances is step one toward asserting rights effectively and meeting legal obligations successfully.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on Legal Insights is provided for general informational purposes only. It is intended to offer insights, commentary, and analysis on legal topics and developments, and should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for professional consultation with a qualified attorney.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general informational purposes only. Laws and regulations may vary by jurisdiction and may change over time. The application of legal principles depends on specific facts and circumstances.

Legal Insights is not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content, or for any actions taken based on the information provided on this website. Users are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situation before making any legal decisions.