Where the crash happens can decide whether you recover anything.

Comparative Negligence: How Shared Fault Affects Your Injury Claim

You're speeding down the highway—let's say 15 over—when another driver runs a red light and T-bones your car. Or maybe you're texting while walking through a grocery store and slip on a wet floor that has no warning sign. Who pays for your injuries when both parties made mistakes?

Most states now use comparative negligence to answer this question. Here's the basic idea: you can still pursue money for your injuries even when you share some blamer. The twist? Your award drops proportionally to match whatever responsibility you carried.

This wasn't always the case. Older laws said that if you were even 1% responsible for your accident, you got nothing. Zero. Zip. Talk about harsh.

These days, forty-six states have ditched that unfair system. But the rules vary wildly depending on where your accident happened. Some jurisdictions let you collect compensation no matter how reckless you were. Others slam the door shut the moment you shoulder half the blame or more.

Understanding these rules matters because small differences in your fault percentage can swing your compensation by tens of thousands of dollars—or eliminate it completely.

What Is Comparative Negligence in Personal Injury Law?

Think of comparative negligence as a mathematical formula that adjusts what you receive based on your role in causing the incident. The shared fault doctrine operates on this principle: when you bear 30% responsibility for a car accident resulting in $100,000 worth of harm, you walk away with $70,000 from the other driver.

Mississippi passed the first law recognizing this principle back in 1910, but most states didn't jump on board until much later. The real shift happened during the 1970s and 80s when state legislatures realized the old system—called contributory negligence—produced absurd results. Imagine losing your entire case because you were 2% at fault. That's what used to happen.

Why the change? Simple fairness. When two people both screw up and cause an accident, why should the person who made a smaller mistake lose everything? Each person should pay based on how much they actually contributed to the harm.

Courts now apply this principle across almost every type of injury case you can imagine. Car wrecks? Absolutely. Slip-and-falls? Yep. Medical malpractice? You bet. Defective products? Most of the time. Workplace injuries? Often, though workers' comp has its own rules.

Every comparative negligence case boils down to three critical questions: What percentage of fault does each party carry? What's the total dollar value of all your injuries and losses? Does your state allow you to recover anything given your assigned fault percentage?

The answer to that final question shapes everything that follows.

Pure vs. Modified Comparative Negligence: State-by-State Differences

American states have split into three camps when it comes to how they handle shared fault. Where your accident happened determines which system applies—and whether you'll see a dime.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Pure Comparative Negligence States

The pure system is the most forgiving. You can recover damages no matter how much responsibility you carry. A plaintiff who shoulders ninety-nine percent of the blame still walks away with compensation representing one percent of their total losses.

Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Washington have all embraced this framework—that's thirteen jurisdictions total.

Here's a real-world example. A California motorcyclist blows through a stop sign but gets hit by a drunk driver going 90 mph. The jury decides the motorcyclist is 60% responsible. Under this pure system, that rider still collects 40% of a $500,000 verdict—that's $200,000.

Critics say this system lets mostly-at-fault plaintiffs shake down defendants who bear minimal responsibility. Supporters argue it's the only truly fair approach because everyone pays exactly what they owe.

Modified Comparative Negligence (50% Bar Rule)

Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Nebraska, North Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia follow a middle path—twelve states in total.

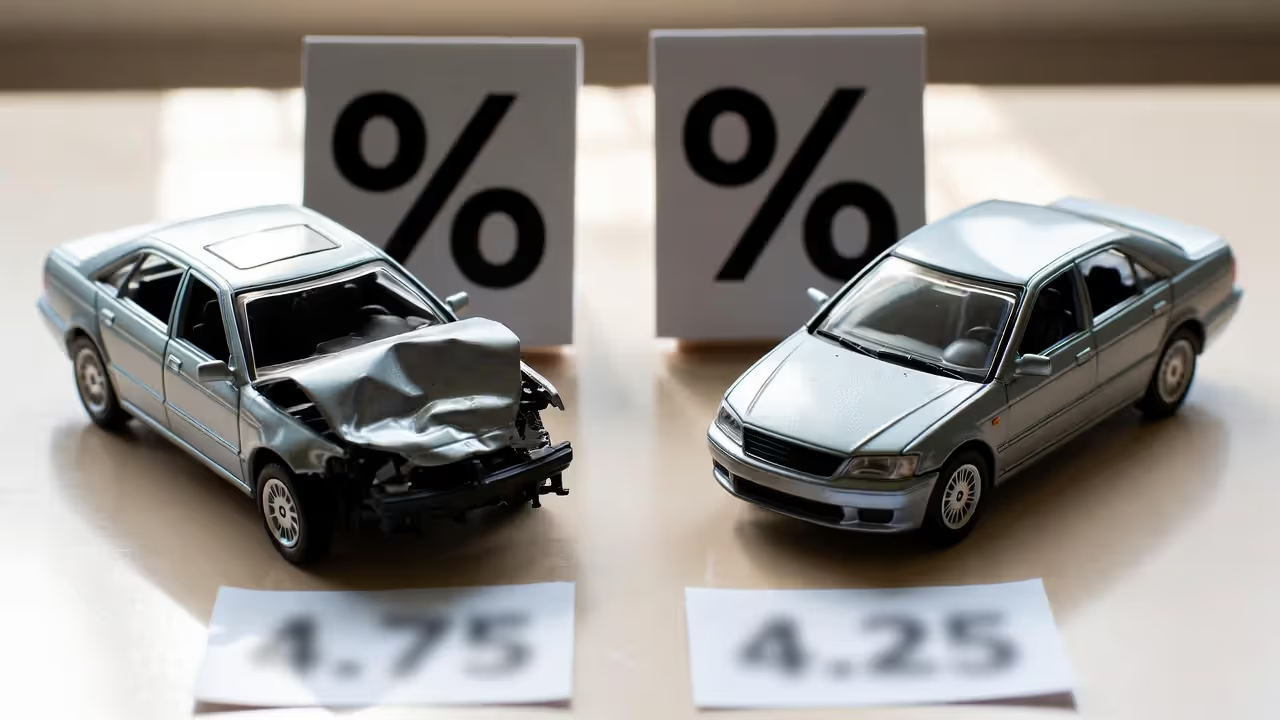

This framework completely blocks your recovery once your responsibility hits the fifty-percent mark. Fall to forty-nine percent? You collect the remaining fifty-one percent of what you're owed. Reach that fifty-percent threshold? You receive absolutely nothing.

This creates a massive cliff effect. Consider a case worth $200,000. If the jury assigns you 49% responsibility, you walk away with $102,000. If they assign you 50%, you get zero. One percentage point equals $102,000.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Defense lawyers in these states fight like hell to push your fault percentage above that 50% line. They understand that crossing this threshold kills your entire claim, transforming the case from "how much do we pay?" to "we pay nothing."

Modified Comparative Negligence (51% Bar Rule)

Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming all use this alternative cutoff—twenty-three states following this model.

Under this approach, you maintain your right to compensation provided your responsibility doesn't surpass the defendant's. You only lose everything when you become more than fifty-percent liable.

Seems like a tiny difference, right? Just one percentage point. But it matters enormously when fault divides evenly.

Let's say a Texas pedestrian is crossing legally in a marked crosswalk at night while wearing dark clothes. The jury finds them 50% at fault. Because Texas follows this more lenient threshold, that pedestrian still collects half their total damages. If this same accident happened in Georgia (which uses the stricter bar), they'd receive nothing at all.

| State | System Type | Recovery Allowed at 50% Fault? | Recovery Allowed at 51% Fault? |

| California | Pure | Yes | Yes |

| Florida | Pure | Yes | Yes |

| New York | Pure | Yes | Yes |

| Texas | Modified (51% bar) | Yes | No |

| Illinois | Modified (51% bar) | Yes | No |

| Pennsylvania | Modified (51% bar) | Yes | No |

| Ohio | Modified (51% bar) | Yes | No |

| Georgia | Modified (50% bar) | No | No |

| Colorado | Modified (50% bar) | No | No |

| Tennessee | Modified (50% bar) | No | No |

| Alabama | Contributory | No | No |

| Maryland | Contributory | No | No |

| North Carolina | Contributory | No | No |

| Virginia | Contributory | No | No |

| Washington D.C. | Contributory | No | No |

How Courts Calculate Fault Percentages in Accident Cases

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Assigning fault percentages isn't some precise science. It's subjective as hell. Two different juries hearing identical evidence regularly reach completely different conclusions.

Courts evaluate how severely each party departed from what a reasonable person would've done. A driver who was texting, speeding 20 mph over the limit, AND running a red light gets hammered with a higher fault percentage than someone who just glanced away from the road for two seconds.

But here's what many people miss: the number of mistakes matters less than how directly those mistakes caused the crash. You might've been driving with an expired registration, but if you're sitting properly stopped at a red light when someone rear-ends you, that registration violation didn't cause anything. It shouldn't increase your fault percentage at all.

Timing plays a huge role. The party whose negligence happened most recently or most directly triggered the accident usually shoulders the heaviest blame. In multi-vehicle pile-ups, whoever started the chain reaction typically gets the biggest percentage, even when other drivers also screwed up.

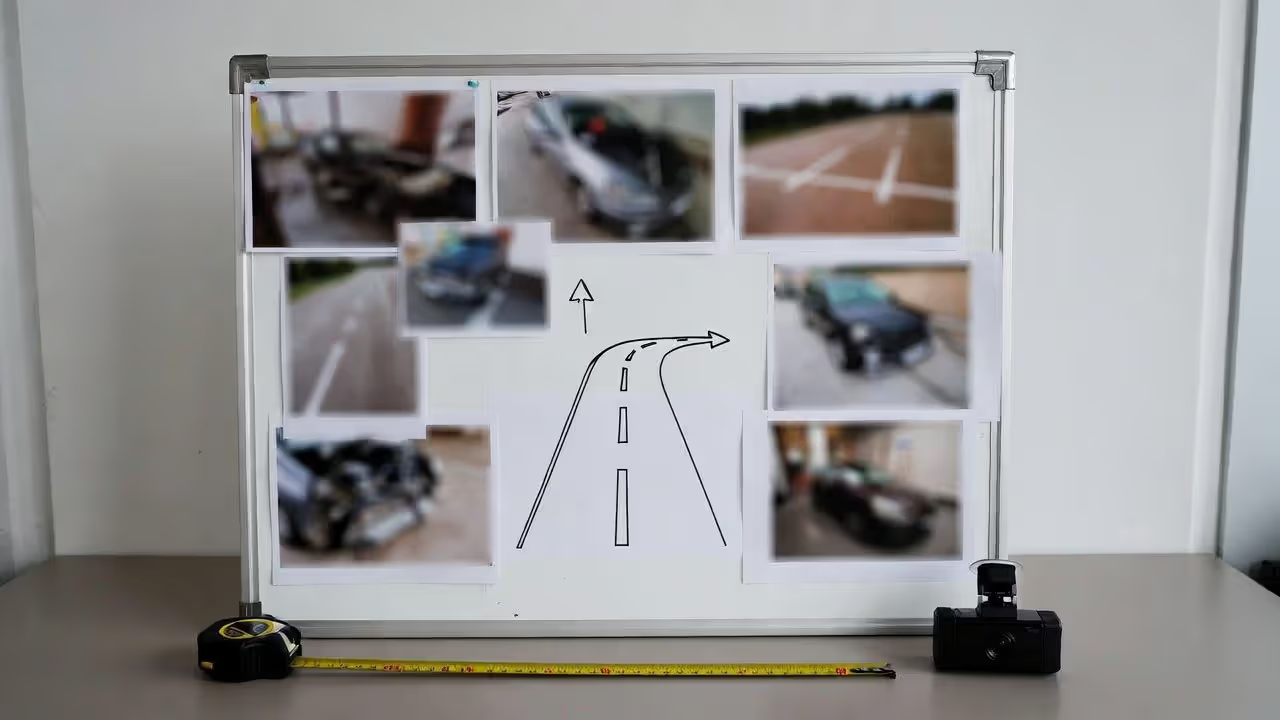

Insurance adjusters make the first call on fault percentages. They review police reports, interview witnesses, look at photos of vehicle damage, and sometimes hire accident reconstruction experts. Most insurance companies have internal guidelines that assign standard percentages to common scenarios. Rear-end collisions? The following driver usually gets tagged with 80-100% fault. Left-turn accidents? The turning driver typically gets 70-90%.

But these initial determinations aren't final. Your lawyer can fight them by presenting contradictory evidence: witness statements that dispute the police report, surveillance video showing the other driver's excessive speed, cell phone records proving they were texting at impact.

When cases go to trial, juries make the final call. The judge explains what negligence means legally, then asks jurors to assign percentages to each party. There's no formula. Jurors discuss what they've seen and heard, then agree on numbers that feel right to them.

What influences their decision? Traffic violations carry weight—speeding, running red lights, illegal lane changes. Distractions and impairments matter enormously—cell phone use, drunk driving, drowsy driving. Loss of vehicle control suggests negligence. Safety code violations like broken brake lights or bald tires increase fault.

Hard evidence beats testimony every time. A video showing exactly what happened trumps two people telling conflicting stories. Police diagrams documenting skid mark length prove speed more convincingly than someone's denial.

The negligence percentage rule gives juries flexibility to account for complex scenarios without forcing them into a simple "liable or not liable" box. That's why virtually identical accidents sometimes yield wildly different percentage outcomes.

Comparative Negligence vs. Contributory Negligence: Critical Differences

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Only four states plus D.C. still use contributory negligence: Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia. This ancient doctrine says that if you contributed to your own injury in any way—even 1%—you recover nothing.

The difference in outcomes is staggering. Take a Maryland driver who's 5% responsible for a crash caused mainly by a drunk driver. That person gets zero compensation. The exact same accident happening just across the state line in Pennsylvania (which uses modified comparative negligence) would allow recovery of 95% of all damages.

This produces ridiculous results. A pedestrian lawfully crossing in a crosswalk might get nothing because they were glancing at their phone and didn't see the reckless driver barreling toward them. Doesn't matter how outrageously the driver behaved—any contributory fault kills the claim.

These holdout states have carved out limited exceptions to soften the harshness. The "last clear chance" doctrine allows recovery when the defendant had the final opportunity to avoid the accident despite your earlier negligence. If you drift slightly over the center line but the oncoming driver sees you with plenty of time to swerve yet doesn't, you might still recover under this narrow exception.

These jurisdictions also apply contributory negligence asymmetrically. It only bars plaintiffs from recovering, not defendants from owing money. A defendant whose negligence contributed to an accident doesn't escape liability just because another defendant was also negligent.

The practical effect? Contributory negligence states heavily favor defendants and insurance companies. Injured people accept lowball settlements because any evidence of their fault—no matter how trivial—risks complete defeat at trial. Defense attorneys only need to prove minimal plaintiff negligence to win, rather than haggling over specific percentages.

Maryland carved out a narrow exception for strict product liability cases, recognizing that misusing a defective product shouldn't completely eliminate recovery. But these exceptions remain limited, and the harsh general rule still governs most injury claims.

Legislative efforts to reform contributory negligence in these states have repeatedly failed. Insurance industry lobbying and political resistance preserve the status quo despite criticism from legal scholars and consumer advocates.

How Your Negligence Percentage Reduces Your Compensation

The math is simple: Total Damages × (100% - Your Fault %) = Your Recovery. But the financial consequences vary dramatically based on your assigned percentage and which state system applies.

A $300,000 jury verdict where you're 30% at fault yields $210,000. That same $300,000 verdict where you're 60% responsible gives you $120,000 in pure comparative negligence states but zero in modified states.

Justice is a kind of proportionality

— Aristotle

Both economic damages (medical bills, lost wages, property damage) and non-economic damages (pain, suffering, emotional distress) get reduced by the same percentage. Some people wrongly assume courts only reduce the subjective pain and suffering stuff, but the percentage cuts everything equally.

Threshold percentages create cliff effects in modified states. Picture someone with $400,000 in proven damages:

- At 40%: Receives $240,000

- At 49%: Receives $204,000

- At 50% in stricter jurisdictions: Receives nothing

- At 50% in more lenient states: Receives $200,000

- At 51% under either modified framework: Receives nothing

One percentage point at that threshold can mean losing or gaining $200,000+.

Calculation Examples by State Type

| Total Damages | Your Fault % | System Type | Amount You Recover | Amount Reduced |

| $500,000 | 20% | Pure | $400,000 | $100,000 |

| $500,000 | 50% | Pure | $250,000 | $250,000 |

| $500,000 | 75% | Pure | $125,000 | $375,000 |

| $300,000 | 49% | Modified (50% bar) | $153,000 | $147,000 |

| $300,000 | 50% | Modified (50% bar) | $0 | $300,000 |

| $300,000 | 50% | Modified (51% bar) | $150,000 | $150,000 |

| $300,000 | 51% | Modified (51% bar) | $0 | $300,000 |

| $200,000 | 25% | Any comparative system | $150,000 | $50,000 |

Multiple defendants complicate these calculations. When three parties share blame—you at 20%, defendant A at 50%, defendant B at 30%—you can typically recover 80% of your total damages, split between the defendants based on their share or through joint liability rules (which vary by state).

Settlement negotiations focus heavily on disputing fault percentages. Defense lawyers often concede their client bears some liability but fight aggressively over the percentage, knowing that shifting it by 10% costs less than fighting over the damage amount. A defense attorney might offer to settle a $300,000 claim for $180,000 by arguing you're 40% at fault rather than the 20% your lawyer claims.

Pre-lawsuit mediation sessions frequently split the difference between competing fault assessments. When you say you're 10% responsible and the defense says 60%, mediators often suggest resolving at 35%—not because that's accurate, but because it's the midpoint. Understanding this negotiation dynamic helps you evaluate settlement offers realistically.

The damages reduction doctrine also affects subrogation claims. When your health insurer paid $50,000 in medical bills and you later recover $100,000 after being assigned 30% fault, the insurer's reimbursement right gets reduced by that same 30%. They recover $35,000, not the full $50,000 they paid.

Common Mistakes That Increase Your Fault Percentage

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

People accidentally inflate their own fault percentages through careless decisions made right after accidents and during the claims process. These mistakes are completely avoidable.

Apologizing at the accident scene seems polite, but "I'm sorry, I didn't see you" becomes an admission that you weren't paying proper attention. Stick to exchanging required information for the police report. You can show concern for others' welfare without accepting blame.

Talking to the other party's insurance adjuster without a lawyer is dangerous. Adjusters ask innocent-sounding questions designed to extract admissions: "Were you in a hurry?" "What were you doing right before the crash?" "How familiar are you with that road?" Your answers get recorded and weaponized to increase your fault percentage.

Social media posts give defense attorneys ammunition. A Facebook photo of you hiking three weeks after claiming severe back injuries suggests either you're not as hurt as claimed or you're recovering faster than alleged—potentially increasing your comparative fault for failing to mitigate damages.

Failing to document evidence immediately after an accident weakens your position. Take photos of vehicle positions, skid marks, traffic signals, weather conditions, and road hazards right away. These details disappear fast but prove crucial in fault battles. A photo showing the other driver's bald tires or the green light you had supports your version of events.

Delaying medical treatment creates gaps that defense lawyers exploit mercilessly. When you wait three weeks between the accident and your first doctor visit, it suggests less serious injuries or implies something else caused your complaints. Adjusters routinely inflate plaintiff fault percentages when they spot treatment delays, claiming you made your own injuries worse by not getting prompt care.

Giving inconsistent descriptions of how the accident occurred destroys your credibility. Your story to police, your lawyer, your doctors, and during your deposition should align on all key facts. Contradictions about vehicle speed, signal colors, or right-of-way make you look unreliable, prompting juries to assign you higher fault.

Destroying evidence—even accidentally—can trigger adverse inference instructions. When you repair your damaged vehicle before the defense inspects it or throw away torn clothing from a fall, courts may tell juries to assume that missing evidence would've proven your fault.

Not contesting traffic tickets from the accident concedes negligence. Fighting a citation for following too closely or failing to yield costs a few hundred bucks but prevents that conviction from serving as powerful evidence of carelessness in your civil case. Traffic convictions don't automatically determine civil fault, but they create strong presumptions that are hard to overcome.

Frequently Asked Questions About Comparative Negligence

Understanding Your Rights Under Comparative Negligence

Comparative negligence transformed American personal injury law by replacing all-or-nothing rules with a system that acknowledges reality: most accidents involve mistakes from multiple people. Sharing partial responsibility doesn't destroy your right to fair compensation—it just adjusts what you recover to reflect everyone's actual contribution.

Where your accident occurred determines which framework applies and whether specific thresholds might eliminate your recovery entirely. Pure comparative negligence states offer the most generous approach, allowing compensation regardless of your fault percentage. Modified comparative negligence states create cutoff points that can completely bar recovery once you cross the 50% or 51% line.

Protecting your claim's value requires careful attention to how fault gets calculated and assigned. Document everything immediately after the incident. Avoid statements that acknowledge responsibility. Get prompt medical care. Hire qualified legal counsel before talking to insurance adjusters. Small mistakes during the first few days after an accident can inflate your fault percentage by 10, 20, or 30 points—costing you tens of thousands in reduced compensation.

Disputes over fault percentages represent critical battlegrounds in injury cases. Defense lawyers and adjusters work aggressively to inflate your percentage, knowing each point they add reduces what they pay. Understanding the liability apportionment law in your state and knowing what evidence influences percentage calculations gives you leverage during settlement talks.

Whether you receive full compensation, partial compensation, or nothing often comes down to arguing over just a few percentage points. The gap between 49% versus 51% fault in a modified comparative negligence state can mean hundreds of thousands of dollars. These enormous stakes make skilled legal representation essential when comparative negligence principles apply to your claim.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on skeletonkeyorganizing.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to showcase fashion trends, style ideas, and curated collections, and should not be considered professional fashion, styling, or personal consulting advice.

All information, images, and style recommendations presented on this website are for general inspiration only. Individual style preferences, body types, and fashion needs may vary, and results may differ from person to person.

Skeletonkeyorganizing.com is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for actions taken based on the information, trends, or styling suggestions presented on this website.