Recent rulings are redefining how business contracts are enforced.

Contract Law Developments Reshaping Business Agreements in 2024–2025

Business lawyers didn't see this coming five years ago: emails now routinely create binding contracts, algorithms draft enforceable terms, and pandemic litigation permanently changed how courts view "impossible" performance. If you're still using contract templates from 2019, you're operating with outdated assumptions about what courts will enforce.

Here's what changed. Appellate courts across the U.S. have tightened some rules (liquidated damages face tougher scrutiny) while relaxing others (informal communications can bind parties even without signatures). Technology threw curveballs that judges are still figuring out—can blockchain code constitute a "signed writing"? Do contracts generated by ChatGPT hold up when disputes arise?

The practical risk? Your standard agreements might contain provisions that courts in your jurisdiction won't enforce, or they might create obligations you never intended. Let's examine the specific rulings, statutory changes, and doctrinal shifts that matter most.

Major Federal Court Rulings That Changed Contract Enforcement Standards

Four decisions from 2023–2024 altered fundamental assumptions about contract formation and breach remedies. Each one affects how in-house counsel should draft future agreements.

Seventh Circuit: Midwest Logistics v. Prairie Distribution (2023)

Two logistics companies exchanged a dozen emails discussing a freight-handling arrangement. Neither party produced a signed document. When one company backed out, the other sued for breach. The Seventh Circuit found an enforceable contract existed.

Why this matters: the court emphasized that businesspeople who begin performing after preliminary discussions can't later claim "we never finalized anything." Objective manifestations of intent—shipping goods, issuing invoices, making payments—trump subjective beliefs about whether a deal was "done." If your sales team starts delivering before paperwork is complete, you've probably created contractual obligations whether you meant to or not.

This represents a meaningful shift in agreement enforcement standards. Ten years ago, most courts would've said "no signed contract, no liability." Now, conduct during negotiations can bind you.

Second Circuit: Castellano v. FinTrust Capital (2024)

An investment agreement contained a forum-selection clause on page 47 of 52 pages, requiring disputes to be litigated in Delaware rather than New York. When litigation arose, the Second Circuit (2-1 decision) declined to enforce the clause.

The majority opinion stressed that inconspicuous placement undermines enforceability even between sophisticated parties. Burying important terms deep in lengthy documents doesn't satisfy the requirement that both sides actually agreed. The dissent argued that accredited investors with legal counsel should read what they sign.

This split reveals judicial disagreement about how much responsibility contracting parties bear. The practical takeaway: put important provisions up front, use formatting (bold text, separate signature lines), and don't assume that sophisticated counterparties waive all challenges. Commercial law rulings like this one force redrafting of standard agreements.

Fifth Circuit: Horizon Energy Partners v. Gulf States Refining (2024)

A construction contract imposed $50,000-per-day penalties for schedule delays. Actual delay costs averaged $8,000 daily according to trial evidence. The Fifth Circuit invalidated the clause as an unenforceable penalty.

The court applied a two-prong test: (1) Were damages genuinely difficult to estimate when parties signed? (2) Does the liquidated amount reasonably approximate probable harm? A 6:1 ratio between liquidated and actual damages failed part two.

You'll see more scrutiny of liquidated damages provisions going forward. Courts increasingly demand proportionality. If your agreements contain these clauses, audit them against likely actual damages. A liquidated amount that exceeds realistic losses by 200-300% might not survive challenge.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Supreme Court: Archer & White Sales Co. v. Henry Schein, Inc. (Continuing Impact)

Though decided in 2019, this arbitration case continues generating 2024 district court applications. The holding: if parties delegate threshold arbitrability questions to an arbitrator, courts won't second-guess even facially frivolous arbitration demands.

Three 2024 district courts compelled arbitration despite arguments that claims fell outside arbitration clauses' scope, citing Archer's command that delegation agreements mean what they say. This agreement enforcement update matters because judicial review disappears—once you've agreed the arbitrator decides "who decides," courts step back entirely until an award issues.

How Digital Transformation Is Driving Contract Doctrine Evolution

Technology keeps creating situations that nineteenth-century contract rules don't quite fit. Courts are adapting doctrine in real time.

E-Signature Validity and Blockchain-Based Agreements

Standard e-signature platforms cause zero controversy anymore. DocuSign, Adobe Sign, HelloSign—courts routinely enforce contracts signed through these services under ESIGN and UETA. That battle is over.

Blockchain-based agreements present harder questions. Smart contracts (self-executing code on distributed ledgers) automatically perform when conditions trigger. No lawyers, no emails, just code.

A Texas federal judge confronted this in Denton County v. Crypto Escrow LLC (2024). Two parties used an Ethereum smart contract to handle an asset transfer. Dispute arose; one side claimed the code didn't reflect their agreement. The court enforced the smart contract—but only because preliminary emails showed both parties understood and approved the code's operation.

That qualification matters enormously. Raw blockchain code, standing alone, might fail for lack of "meeting of the minds." How can parties manifest mutual assent if they interact pseudonymously and never discuss terms in English? The Texas court required off-chain evidence (those preliminary emails) showing genuine agreement.

Here's the practical guidance for companies experimenting with distributed ledgers: maintain a paper trail proving counterparties reviewed the code and confirmed it matched their deal. Screenshots, email confirmations, test transactions—anything demonstrating that both sides knew what the smart contract would do.

AI-Generated Contracts and Legal Recognition Challenges

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Large language models now churn out entire agreements from brief prompts. Type "draft a software license for SaaS product with annual subscription," hit enter, get back twelve pages of legalese in forty seconds.

Will courts enforce terms that no human negotiated? Mostly yes—if both parties had opportunity to review before signing. Courts don't care whether a human or algorithm drafted the language. They care whether both sides manifested assent to specific provisions.

The exception: when AI inserts provisions neither party discussed. Pemberton Industries v. Apex Manufacturing (Illinois state court, 2024) involved an addendum generated by AI. The model included an indemnification clause that neither company's representative mentioned during negotiations. The clause used terminology inconsistent with the parties' prior contracts.

Illinois court's holding: no enforcement. Automated drafting can't substitute for actual agreement on material terms. The judge noted that indemnification shifts significant risk—parties must consciously accept such terms, not stumble into them via algorithmic insertion.

Three rules for AI-generated contracts: (1) review output carefully before sending, (2) delete provisions that don't reflect your actual deal, (3) document important terms in a term sheet or email before feeding anything to the AI. Don't let the algorithm negotiate for you.

State-Level Variations in Commercial Law Rulings: What Businesses Must Know

Contract law stays mostly state-level, and recent decisions show growing divergence. Multi-state companies face a compliance patchwork.

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

State-by-State Contract Law Differences (2024–2025)

| Jurisdiction | Non-Compete Rules | Liquidated Damages | Unconscionability Analysis | Key 2023-24 Decision |

| California | Nearly always unenforceable per Bus. & Prof. Code § 16600; narrow trade secret exception | No statutory limit; courts review reasonableness | Uses sliding-scale test combining procedural and substantive factors | Ixchel Pharma v. Biogen (2023): Court rejected attempt to enforce non-compete via trade secret carve-out |

| Texas | Valid if reasonable in duration, geography, and scope of restricted activity | No cap; subject to reasonableness analysis | Requires showing gross disparity in bargaining power | Marsh USA v. Cook (2024): Upheld 2-year restriction for VP-level sales executive |

| New York | Enforced when protecting employer's legitimate business interests | No statutory ceiling; penalty doctrine applies if disproportionate | Demands both procedural defects AND substantive unfairness | BDO USA v. Cowen (2024): Non-solicitation clause survived despite covering broad customer list |

| Florida | Presumed valid if duration ≤2 years | No maximum; proportionality review | Focuses primarily on substantive one-sidedness | Proudfoot Consulting v. Gordon (2023): Court enforced 6-month covenant for entry-level employee |

| Delaware | Enforced with deference to sophisticated parties' bargains | No cap; courts rarely intervene | Very high threshold; seldom found in commercial contexts | TransDigm v. Aero Fastener (2024): Refused to modify overbroad geographic restriction |

| Illinois | Valid if ancillary to legitimate employment relationship | No statutory limit; reasonableness standard controls | Requires both procedural irregularities AND substantive imbalance | Fifield v. Premier Dealer Services (2024): Struck down "nationwide" geographic scope as excessive |

Non-compete enforcement varies wildly. California essentially bans them—forcing employers to rely on trade secret protection and customer non-solicitation. Texas and Florida enforce reasonable restrictions, though "reasonable" depends heavily on employee seniority and industry context. Delaware rarely second-guesses commercial agreements between sophisticated entities.

Liquidated damages scrutiny occurs everywhere but with different intensity. Some courts ask if the amount seemed reasonable at contract formation (ex ante test). Others evaluate proportionality against actual breach harm (ex post test). That Fifth Circuit Horizon Energy decision illustrates the stricter ex post approach—courts increasingly demand that liquidated figures bear reasonable relationship to real losses.

Unconscionability standards split between conjunctive and sliding-scale tests. New York requires proving both procedural defects (unequal bargaining, hidden terms) AND substantive unfairness (one-sided provisions). California uses a sliding scale—extreme substantive unfairness can overcome minimal procedural problems, and vice versa. This difference affects which contracts survive challenge.

Multi-state businesses should pick governing law strategically for each agreement type. Don't default to headquarters state. Consider which jurisdiction's substantive rules best protect your interests. Most states enforce choice-of-law clauses in commercial contracts between sophisticated parties (consumer agreements get tougher scrutiny).

Recent Changes to Contract Interpretation Standards and Ambiguity Rules

Traditional interpretation rules say: give words their plain meaning, ignore outside evidence if language seems clear. Several recent developments complicate that framework.

Plain Meaning Doctrine Gets Mushier

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 212 tells courts to interpret agreements from the standpoint of a reasonable person aware of all relevant circumstances. Modern decisions increasingly consider industry custom and prior dealings even when contractual language appears unambiguous.

Keystone Steel v. Industrial Fabricators (Pennsylvania Superior Court, 2024): Contract defined "FOB delivery" in seemingly clear terms. Court admitted expert testimony about steel-industry trade usage anyway, reasoning that technical terms carry specialized meanings that standard definitions miss.

Implication: defining terms in your contract doesn't necessarily insulate you from extrinsic evidence. If your industry gives common phrases specific meanings, courts may override your definitions based on trade usage. This represents a subtle shift in contract interpretation doctrine—"plain meaning" isn't as plain as it used to be.

Parol Evidence Rule Weakening

The parol evidence rule traditionally bars using pre-contract negotiations to contradict a fully integrated written agreement. Courts asked whether the writing looked complete on its face (the "four corners" test).

Several jurisdictions now apply a functional approach: would the disputed term naturally be included in a written contract for this type of transaction? If yes, but it's missing, courts suspect the writing isn't actually complete.

Pacific Rim Importers v. Cascade Distribution (Washington Court of Appeals, 2023): Contract contained comprehensive integration clause saying "this agreement constitutes the entire agreement." Court allowed testimony about an alleged oral product warranty anyway. Reasoning: the written contract was silent on product quality—a topic buyers and sellers normally address. Integration clause didn't conclusively prove the writing captured everything.

Lesson: integration clauses help but don't guarantee courts will exclude all extrinsic evidence. Explicitly address every material term in writing. Don't leave important subjects unmentioned, then rely on merger clauses to protect you.

Contract law evolves not in theory, but in response to commercial practice and judicial refinement.

— E. Allan Farnsworth, Columbia Law School

Good Faith Obligations Expanding

Every contract includes an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. States define this differently—some limit it to honoring reasonable expectations, others prohibit exercising contractual discretion opportunistically.

Commonwealth Energy v. Reliable Power Corp. (Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, 2024): Buyer entered requirements contract (obligated to purchase all needs from seller). Market prices dropped. Buyer reduced "requirements" to nearly zero to avoid unfavorable contract price.

Massachusetts high court: breach of implied covenant. Buyer's discretion to determine requirements didn't extend to eliminating them entirely to escape a bad bargain. This ruling expands good-faith obligations beyond simple honesty to include not exploiting discretion opportunistically.

Watch for similar expansions in other jurisdictions. Contract interpretation developments increasingly impose obligations that written terms don't explicitly state.

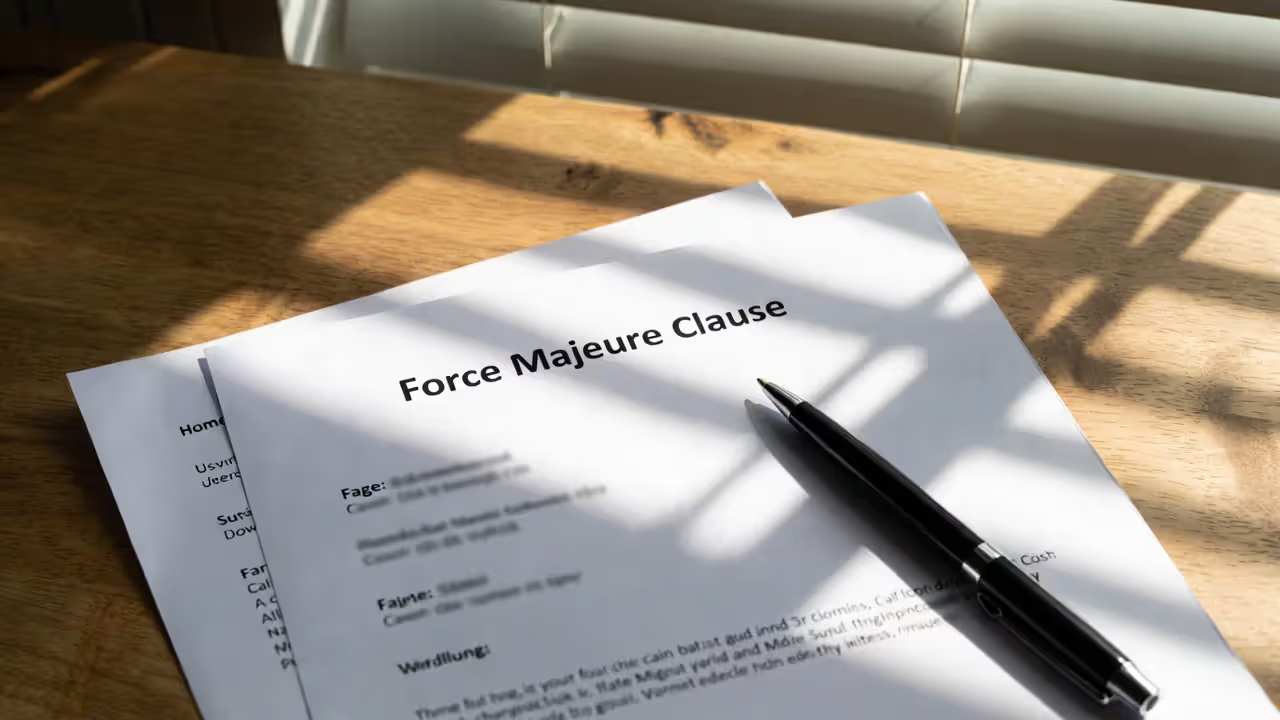

Force Majeure and Impossibility Doctrines After Post-Pandemic Precedents

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

COVID-19 litigation generated appellate decisions clarifying when performance excuses apply. These rulings will govern the next crisis, whatever form it takes.

Impossibility vs. Impracticability: The Distinction Matters

Common-law impossibility requires objective impossibility—literally cannot perform, not merely "it got harder/more expensive." Courts distinguish this from impracticability, which excuses performance when unforeseen events make it extraordinarily burdensome.

Most pandemic impossibility claims failed. JN Contemporary Art v. Phillips Auctioneers (New York Court of Appeals, 2023): Art gallery claimed government-mandated closures made payment obligations impossible. Court rejected the argument—contract required payment, not physical presence. Gallery could've paid remotely. Closure didn't make payment objectively impossible.

Impracticability fared slightly better when performance required in-person activity that regulations specifically prohibited. Florida appellate court excused wedding venue's performance when executive orders banned gatherings, reasoning that hosting events was the contract's essential purpose and regulations directly prevented it.

Takeaway: "impossibility" means what it says. Financial hardship doesn't count. Performance must become literally impossible, not just unprofitable.

Frustration of Purpose: When Your Reason for Contracting Disappears

This doctrine excuses performance when unforeseen events destroy your reason for entering the contract, even though performance remains physically possible. Courts require: (1) frustrated purpose was the contract's foundation, (2) both parties recognized this at formation, (3) frustrating event was unforeseeable.

Lakeshore Events v. Metro Convention Center (Illinois Appellate Court, 2024): Convention organizer contracted to rent space for trade show. Public health orders prevented attendees from gathering. Organizer refused to pay rental fees.

Illinois court: frustration of purpose applies. Hosting an in-person convention was the entire point—both parties knew it—and January 2020 contracts couldn't foresee March 2020 pandemic restrictions. Performance (paying rent, providing space) remained possible, but the purpose evaporated.

This represents a narrower path than impossibility. Both parties must have understood the specific purpose at formation. Generic commercial purposes ("make money," "serve customers") won't suffice.

Force Majeure Clauses: Courts Construe Them Narrowly

These provisions excuse performance when listed events occur. Courts interpret them strictly—the triggering event must fall within enumerated categories. Generic catch-alls like "acts of God" or "government action" might not cover pandemics unless the clause specifically mentions disease or health emergencies.

Gulf Coast Refineries v. Permian Transport (Texas Court of Appeals, 2023): Force majeure clause listed "natural disasters, war, and terrorism." Shipper claimed pandemic triggered the clause. Court disagreed—pandemic didn't constitute "natural disaster," and parties could've included disease outbreaks if they'd wanted coverage.

Compare that to contracts containing language like "including but not limited to epidemics, pandemics, quarantines, and public health emergencies"—courts enforced those clauses consistently.

How to Draft Force Majeure Clauses Now

Post-pandemic case law teaches five lessons:

- List pandemics specifically. Don't rely on "acts of God" or "government action." Use explicit terms: epidemics, pandemics, public health emergencies, quarantine orders.

- Distinguish mandates from recommendations. Does a government "recommendation" to limit gatherings trigger the clause, or must it be a legally enforceable order? Specify which.

- Clarify economic hardship. Does financial difficulty alone suffice, or must performance become legally prohibited? Courts default to requiring legal impossibility unless you specify otherwise.

- Address notice and mitigation. How quickly must the affected party notify counterparty? What steps must they take to minimize disruption? Spell this out.

- Specify suspension vs. termination. Does force majeure temporarily suspend performance, or does it terminate the contract entirely? If suspension, how long before termination rights arise?

Many companies updated templates in 2021-22 but haven't touched them since. Current drafting should incorporate three years of case law showing what language courts actually enforce.

Common Mistakes Companies Make When Adapting to New Contract Law Standards

Author: David Kessler;

Source: skeletonkeyorganizing.com

Mistake #1: Recycling Pre-2020 Templates

Forms drafted before the pandemic likely ignore: - Remote work provisions (who owns equipment? what law governs home-state employees?) - Enhanced force majeure language reflecting post-pandemic case law - Updated electronic signature protocols - Data privacy requirements under newer state statutes

Association of Corporate Counsel's 2024 survey found 40% of in-house legal departments use contract templates older than five years. Non-compete enforceability, arbitration scope, and force majeure interpretation all shifted substantially during that period.

Fix: Schedule annual template reviews. Flag provisions referencing superseded statutes or embodying pre-pandemic assumptions about in-person performance.

Mistake #2: Picking Governing Law Without Strategy

Multi-state businesses often default to headquarters-state law. This ignores strategic advantages certain jurisdictions offer.

Delaware and New York provide extensive contract case law and generally favor enforceability (helpful if you're the drafter). California offers strong consumer protections but voids non-competes and restricts class-action waivers (helpful if you're the consumer/employee, harmful if you're the employer/business).

Example: Software company headquartered in California that selects California law inadvertently voids employee non-competes. Same company might benefit from California's prohibition on contractual jury waivers if it expects disputes where juries favor plaintiffs.

Consider governing law tactically for each contract type. Employee agreements, customer terms, and supplier contracts may benefit from different jurisdictions' rules.

Mistake #3: Ignoring Your Own "No Oral Modification" Clauses

Standard contracts state amendments require signed writing. Courts increasingly disregard these provisions when parties' conduct demonstrates mutual intent to modify.

Pacific Building Supply v. Contractors Warehouse (Ninth Circuit, 2024): Contract contained "no oral modification" clause. Parties repeatedly accepted change orders via email without formal signatures. Court held the parties waived the NOM clause through course of performance—sophisticated commercial entities that repeatedly ignore their procedures can't invoke them opportunistically later.

Two solutions: (1) Actually follow your modification procedures—don't accept informal changes if your contract prohibits them; (2) Strengthen NOM language by specifying required signature method ("signed by each party's authorized officer in writing delivered via certified mail") and explicitly stating that course of performance doesn't waive the requirement.

Mistake #4: Using Single National Template for Consumer Contracts

Many states impose requirements beyond common-law contract doctrine. California's Consumers Legal Remedies Act, Massachusetts Chapter 93A, Texas DTPA—these statutes create liability for "unfair" or "deceptive" practices even when contracts technically satisfy formation rules.

A national retailer using identical terms and conditions in all states might violate: - California's prohibition on automatic renewal without conspicuous disclosure - New York's requirement for plain-language contracts in consumer transactions

- Texas's ban on certain warranty disclaimers in consumer sales

The compliance burden of maintaining jurisdiction-specific versions beats the cost of defending statutory violations carrying treble damages and mandatory attorneys' fees.

Mistake #5: Cutting Corners on E-Signature Compliance

ESIGN and UETA validate electronic signatures but impose requirements: parties must consent to electronic transactions, systems must maintain accurate records of signing process.

Riverside Bank v. Coastal Properties (Georgia Court of Appeals, 2023): Bank sought to enforce e-signed promissory note. Couldn't produce audit logs showing when borrower accessed or signed document. Court refused enforcement—without compliance records, no proof signature was authentic.

Use reputable platforms (DocuSign, Adobe Sign) that automatically generate compliance records. Retain audit logs for applicable statute of limitations (typically six years for written contracts). Don't use generic tools lacking robust authentication features.

Frequently Asked Questions About Current Contract Law Changes

These contract law developments—from appellate refinements of enforcement standards to growing state-level divergence on non-competes—demand regular agreement audits and template updates. The gap between legal doctrine and business practice creates risk exposure many companies don't recognize.

Three immediate priorities: (1) Review force majeure clauses to incorporate three years of post-pandemic case law, (2) Confirm choice-of-law provisions align strategically with your interests for different agreement types, (3) Implement tracking systems for appellate decisions in jurisdictions where you operate regularly.

Companies treating contract drafting as a one-time exercise rather than ongoing compliance will discover courts interpreting their agreements in unexpected ways. Staying current with these doctrinal shifts prevents unintended obligations and unenforceable provisions from undermining your deals.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on skeletonkeyorganizing.com is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to showcase fashion trends, style ideas, and curated collections, and should not be considered professional fashion, styling, or personal consulting advice.

All information, images, and style recommendations presented on this website are for general inspiration only. Individual style preferences, body types, and fashion needs may vary, and results may differ from person to person.

Skeletonkeyorganizing.com is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for actions taken based on the information, trends, or styling suggestions presented on this website.